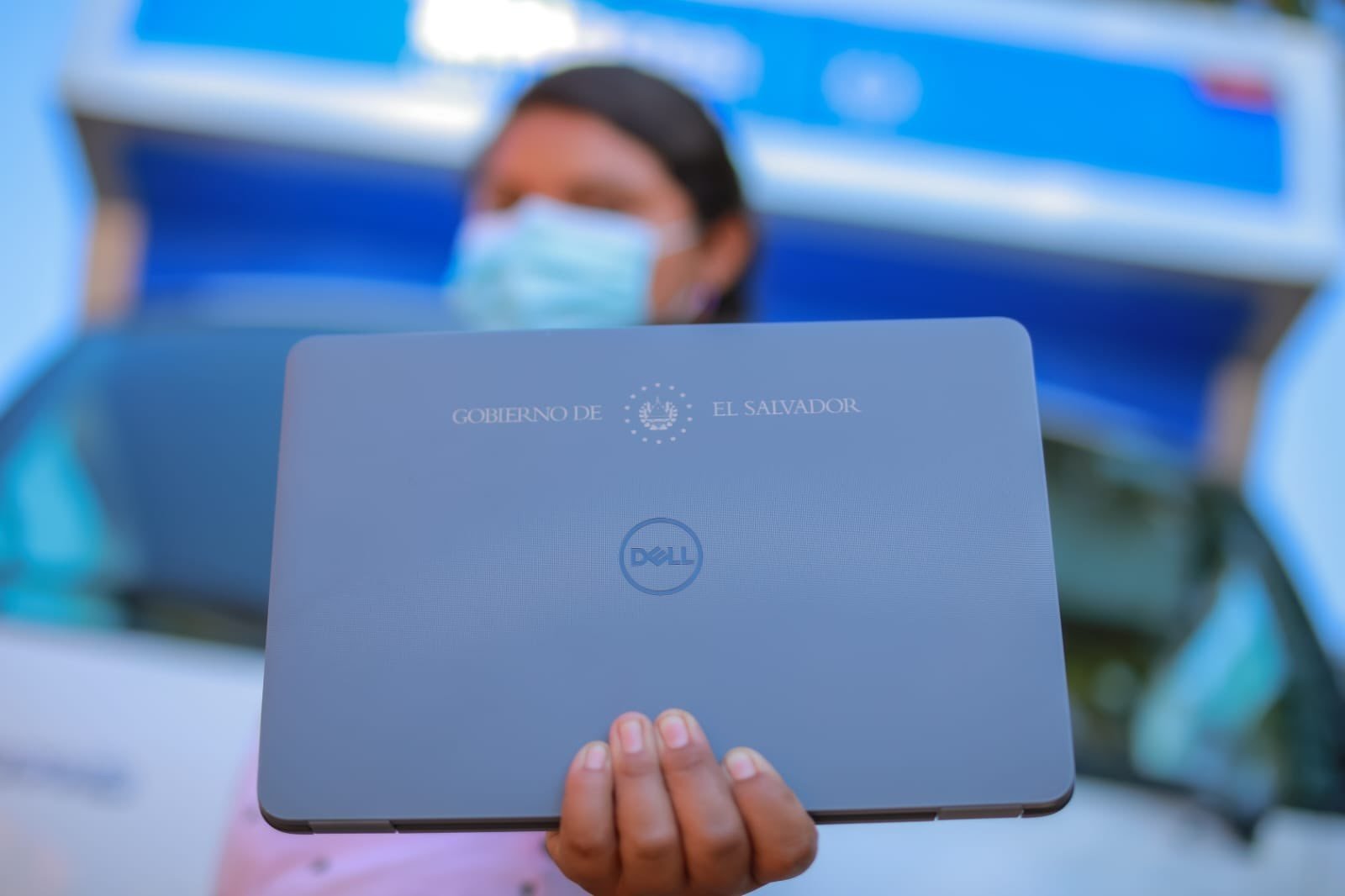

An independent audit conducted in 2023 of the digital divide reduction program—through which the Government of El Salvador distributed computers and tablets to students and teachers—confirmed the purchase of more than half a million devices by the government between 2021 and 2022. However, auditors were unable to verify the physical existence of delivered devices in at least 65% of cases, because the Ministry of Education (MINED) could not locate the students for various reasons, chief among them dropping out of school.

Teachers’ unions warn that although the program initially drove an increase in public school enrollment, many young people did not continue their education.

The audit has been published by the CABEI on its website and covers the program’s execution between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2022. During that period, the Government of El Salvador secured a loan from the CABEI to finance the program, whereby the bank reimbursed the government for funds it had already invested in the purchase of laptops and tablets, totaling $214.7 million.

Details regarding how many devices El Salvador purchased, from whom, the amount paid to each supplier, and the distribution of devices across the country’s schools were placed under seal by MINED in 2021 for a period of seven years, invoking Article 19, subsection (e), of the Access to Public Information Act (Ley de Acceso a la Información Pública). Under this provision, the government may seal information when it forms part of officials’ deliberative processes, so long as no final decision has been reached.

Nonetheless, the published audit contains some of this information, along with figures that shed light on the program’s progress during its first two years.

According to the information MINED shared with the auditing firm, the Government of El Salvador (GOES) intended to benefit 597,493 students and 1,335 primary and secondary school teachers across 10 departments, selected on the basis of multidimensional poverty criteria.

Between January 2021 and December 2022, according to the equipment delivery records with which the GOES requested its first disbursement from the CABEI, 586,741 devices had been acquired. Of these, 586,065 were logged into the Ministry of Education’s equipment database, the audit explains. The discrepancy of 676 devices is flagged by the audit but left unexplained by either the government or the firm that conducted the evaluation.

Meanwhile, through the end of 2022, the ministry reported 585,364 devices delivered to students and teachers. The remaining 701 (relative to those registered) were delivered in 2023, handed over to technical support, or held in reserve, the ministry told auditors.

No Physical Verification

Armed with acquisition and delivery figures, the auditing firm undertook a review of the distribution process. MINED reported that it had dispatched the devices to 29 distribution hubs nationwide, from which they were then transferred to individual schools.

According to the audit, “the hubs maintain delivery records documenting the handover of equipment to school principals for distribution to final beneficiaries.” However, the auditors noted that these records did not include device serial numbers or identify the funding source, and that equipment financed through different funding streams had been commingled.

Furthermore, the audit found that none of the 29 distribution hubs maintained records or evidence of equipment delivery to students; instead, that responsibility was delegated entirely to the schools themselves.

With this information, the auditors selected a sample of 60 schools that had received devices, which they visited to carry out physical inspections.

In total, these 60 schools received 3,554 devices for distribution to students and teachers. The audit team visited them and confirmed that delivery records existed for 99% of the equipment, yet was unable to conduct physical inspections because the ministry could not contact the recipients.

The audit states: “During our visits, we were only able to verify equipment in 35% of the cases expected by the audit. Regarding the 65% of devices we could not physically examine, MINEDUCYT reported the categories applicable to the students; however, it did not provide supporting documentation.”

By “categories applicable to the students,” the auditors mean the reasons why certain students who received devices could not be physically located for inspection.

Of the 3,554 devices the audit was to review across the 60 schools, auditors verified the physical existence of 1,241. They were unable to inspect 2,313. Among the reasons MINED offered were students who had graduated (652), students not promoted to the next grade (30), promoted students (59), and dropouts (158).

However, the ministry also invoked two additional categories to account for the unreviewed devices: “enrollment without record” in 1,281 cases, and cases with no explanation whatsoever, totaling 133. The audit emphasizes that in these cases, “no documentation was obtained to evidence and support the data.”

This outlet sought comment from the CABEI, the Salvadoran firm responsible for the audit, and MINED to clarify details of the bank’s published report—including whether a subsequent audit had been conducted to improve verification rates, and what “enrollment without record” means in practice.

Of the three institutions, only the CABEI responded to the request and asked for written questions, which were duly submitted. Although on January 26 the bank said it was working on answers to the questions sent, no further response had been received by the time this article went to press.

Regarding the meaning of “enrollment without record,” Bases Magisteriales (Grassroots Teachers’ Union) explained that this category applies to students who have not continued their studies and do not appear enrolled at any educational institution.

“Every student enrolled in a public school is assigned an NIE (student identification number). That number is used to track the student at whatever school they are enrolled in. This allows MINED to monitor how many students graduate, drop out, or transfer from one school to another. If students have an NIE but cannot be located at any public school or private institution, they have, in short, abandoned their studies—whether temporarily or permanently,” Bases Magisteriales explained.

This would mean that the number of students who dropped out (158) should be combined with those listed as having no enrollment record (1,281). The total would therefore be 1,439 students who received a computer or laptop and abandoned their studies during the program’s first two years of operation—based solely on the sample of 60 schools selected for the audit.

According to the Frente Magisterial Salvadoreño (Salvadoran Teachers’ Front, FMS), when the current program of individual computer distribution began, they observed two phenomena: first, students who had already dropped out returned to schools solely to receive the computers; and second, students enrolled at private institutions opted to transfer into the public system to obtain the devices.

“We started seeing students transferring from private schools to public schools, and they wanted the computer immediately—but it took time; they were not given one right away. There were complaints about why the children coming from private schools were not receiving computers. They expected instant delivery, but distribution was based on the previous year’s enrollment,” the organization stated.

Regarding the second phenomenon, the FMS said that together with several school principals in the San Salvador Metropolitan Area (AMSS), they identified students who had already left the system, returned to the classroom, and subsequently dropped out again.

“When word got out that computers would be distributed, it created a huge commotion, and many children who were already outside the system showed up to enroll—but it was driven by the desire to have a computer. What happened? These children later withdrew; they left; they did not stay in the system. Yes, there was an exodus of students who demanded a computer,” the organization noted.

In that regard, Bases Magisteriales stressed that owning a computer has done nothing to stem school dropout rates in the country.

“Computing devices—computers, laptops, whatever you choose to call them—have not served as a deterrent against dropping out. School desertion is a phenomenon that persists; it is ever-present and tied far more closely to the precarious economic conditions of families. The distribution of a device to each child has not prevented students from leaving school,” the union declared.

Computadoras no frenaron deserción escolar: al menos 1,439 estudiantes dejaron los estudios tras recibir equipos de MINED, revela auditoría

Una auditoría realizada en 2023 por una firma independiente a la ejecución del programa de reducción de brecha digital, con el cual el Gobierno de El Salvador entregó computadoras y tablets a estudiantes y docentes, confirmó la compra de más de medio millón de dispositivos por parte del gobierno entre 2021 y 2022. Sin embargo, la auditoría no pudo constatar la existencia física de los equipos entregados en al menos el 65 % de los casos, debido a que el Ministerio de Educación (MINED) no pudo localizar a los estudiantes por diferentes motivos, entre los cuales el principal fue la deserción escolar.

Sindicatos advierten que, pese a que inicialmente el programa causó incremento en la matrícula de estudiantes dentro del sistema público, muchos jóvenes no continuaron su educación.

La auditoría ha sido compartida por el Banco Centroamericano de Integración Económica (BCIE) en su sitio web, y comprende información sobre la ejecución del programa entre el 1 de enero de 2021 y el 31 de diciembre de 2022. En dicho período, el Gobierno de El Salvador obtuvo del BCIE un préstamo para financiar el programa en mención, con el cual el banco reembolsó al Gobierno los fondos que este ya había invertido en la compra de laptops y tablets, por un monto de $214.7 millones.

Los detalles sobre cuántos equipos compró El Salvador, a quién, el monto pagado a cada proveedor, y la distribución en la asignación de los equipos en los centros escolares del país fue puesta en reserva por el MINED en 2021 por un período de siete años, amparados en el artículo 19, literal e, de la Ley de Acceso a la Información Pública. De acuerdo a este, el Gobierno puede reservar información cuando la misma forme parte del proceso deliberativo de funcionarios, mientras no se tome una decisión definitiva.

Sin embargo, en la auditoría compartida hay información de esto y cifras que permiten identificar los avances del programa en sus dos primeros años.

De acuerdo a la información compartida por el MINED a la firma auditora, el GOES pretendía beneficiar a 597,493 alumnos y a 1,335 docentes de educación básica y media, distribuidos en 10 departamentos, elegidos con criterios de afectación de pobreza multidimensional.

Entre enero de 2021 y diciembre de 2022, según las actas de entrega de equipos con que el GOES solicitó el primer desembolso de fondos al BCIE, se habían adquirido 586,741 equipos. De estos, 586,065 se registraron en la base de datos de equipos ingresados al Ministerio de Educación, según explica la auditoría. La diferencia de 676 es destacada por la auditoría, pero no explicada por el Gobierno o la firma que hizo la evaluación.

En tanto, el ministerio reportó hasta finales de 2022, 585,364 entregados a estudiantes y docentes. Los 701 restantes (con respecto a los registrados) se entregaron en 2023, se entregaron a soporte técnico o estaban en disponibilidad, indicó la cartera a los auditores.

Sin respaldo físico

Con las cifras de equipos adquiridos y entregados, la firma auditora realizó un proceso de revisión de la entrega de los mismos. Para ello, el MINED le informó que distribuyó estos en 29 sedes a nivel nacional, desde las cuales luego trasladó los equipos hacia los centros escolares.

Según la auditoría, “las sedes cuentan con actas de entrega de equipos a directores de Centros Escolares, para ser entregados a beneficiarios finales”. Sin embargo, los auditores advirtieron que en las actas no se compartió información sobre número correlativo de los equipos, ni identificación de la fuente de financiamiento y que se mezclaron equipos tecnológicos financiados con diferentes fuentes de financiamiento.

Asimismo, según la auditoría, en las 29 sedes desde las que se distribuyeron los equipos a los centros escolares no hay registros ni evidencia de la entrega de los equipos a los estudiantes; sino que esta responsabilidad se delegó directamente a los centros escolares.

Con esa información, los auditores elaboraron una muestra de 60 centros escolares que recibieron equipos, para visitar y llevar a cabo la revisión física de equipos.

En total, estos 60 centros recibieron 3,554 equipos para entregar a alumnos y docentes. La auditoría los visitó y confirmó la existencia del 99% de actas de entrega de equipos, pero no pudo realizar una revisión física de estos debido a que el ministerio no pudo contactar a quienes los recibieron.

La auditoría explica: “Durante nuestras visitas, únicamente fue posible verificar los equipos en un 35 % de la expectativa de la auditoría. Al respecto del 65 % de equipos que no pudimos examinar físicamente, el MINEDUCYT informó acerca de las categorías que presentan los estudiantes; sin embargo, no proporcionó documentación de sustento”.

Al referirse a las “categorías que presentan los estudiantes”, los auditores se refieren a las razones por las cuales hubo estudiantes que recibieron equipo tecnológico pero no pudieron ser revisados físicamente por los auditores.

De los 3,554 equipos que la auditoría debía revisar en los 60 centros escolares, verificaron la existencia física de 1,241. No pudieron revisar 2,313. Entre las razones por las cuales el MINED justificó esto se encuentran estudiantes que se graduaron (652), no promovidos (30), promovidos (59) y que desertaron (158).

Sin embargo, hay otras dos categorías que el ministerio también usó para justificar los equipos no revisados. Una es la existencia de “matrícula sin registro” en 1,281 casos, y casos sin explicación con 133. La auditoría enfatiza que, estos casos, “no se obtuvo documentación que evidencie y soporte los datos”.

Este medio gestionó tanto con el BCIE como con la firma salvadoreña a cargo de la auditoría y con el MINED un espacio de consulta para aclarar detalles del informe publicado por el banco, incluido el saber si hubo otra auditoría posterior que permitiera mejorar las cifras de revisión, o qué significa que haya equipos no verificados por “matrícula sin registro”.

De las tres instituciones, solo el BCIE contestó la petición y solicitó las preguntas por escrito, y estas fueron enviadas. Si bien el 26 de enero, el banco dijo estar gestionando las respuestas a las preguntas enviadas, hasta el cierre de esta nota no hubo mayor respuesta.

Sobre el significado de “matrícula sin registro”, Bases Magisteriales explicó que esta categoría se utiliza con estudiantes que no han continuado con sus estudios al no aparecer matriculados en ningún centro educativo.

“A cada estudiante matriculado en la escuela pública se le asigna el NIE(número de identificación estudiantil), con ese número se ubica al alumno en cualquier escuela que esté matriculado. Esto permite al MINED darse cuenta cuántos alumnos egresan, desertan, se van de una escuela a otra. (Si) tienen NIE, pero no se ubican en ninguna escuela pública ni en colegio privado, en síntesis, han abandonado el estudio, ya sea temporal o definitivamente”, explicó Bases Magisteriales.

Lo anterior significaría que la cifra de estudiantes que desertaron (158) debería sumarse con la de estudiantes sin registro de matrícula (1,281). Por tanto, serían 1,439 estudiantes que recibieron computadora o laptop y dejaron sus estudios, en los dos primeros años de ejecución del programa; tomando como base únicamente las 60 escuelas de muestra para realizar la auditoría.

Según el Frente Magisterial Salvadoreño (FMS), cuando comenzó el actual proyecto de entrega de computadoras de forma individual, percibieron dos fenómenos: uno, que los estudiantes que habían desertado regresaron a los centros escolares solo para recibir las computadoras; y dos, que alumnos que estaban en instituciones privadas optaron por matricularse en el sistema público por el beneficio de los dispositivos.

“Se comenzó a ver que de los colegios se pasaban para las escuelas y querían inmediatamente la computadora, pero eso tardó, no se les dio inmediatamente. Había quejas que por qué no les entregaban la computadora a los niños que estaban llegando de los colegios, pensaban que iba a ser inmediatamente la entrega, pero esta se hacía en base a la matrícula del año anterior”, indicó la gremial.

Del segundo fenómeno, el FMS dijo que con varios directores de centros escolares del Área Metropolitana de San Salvador (AMSS) identificaron a estudiantes que ya estaban fuera del sistema, volvieron a las aulas y posteriormente volvieron a abandonar sus estudios.

“Cuando se supo que iban a dar computadoras se hizo una gran bulla y muchos niños que estaban ya fuera del sistema llegaron a matricularse, pero era por el deseo de tener la computadora. ¿Qué sucedió? que (después) estos niños se nos retiraron, se nos iban, no se mantenían en el sistema. Sí, hubo una fuga de alumnos que exigieron la computadora”, señaló la organización al respecto.

En ese sentido, Bases Magisteriales subrayó que tener una computadora, no ha sido motivo para que la deserción escolar se detenga en el país.

“Los equipos informáticos, las computadoras o laptops, como quiera llamársele, no ha sido un atenuante para evitar la deserción escolar. La deserción escolar es un fenómeno que está ahí, es latente y está vinculado más a las precarias condiciones económicas de la familia. Así que la entrega de ese dispositivo a cada uno de los niños no ha evitado la deserción escolar”, manifestó el sindicato.