Delmy insists that her son is innocent and can only prove it with certain documents, which she hasn’t been able to complete because her public defender refuses to give her permission to obtain his criminal records, which would show that her son has never had any issues with the law.

“When I went to find my son’s first lawyer to request authorization for the records, he told me he couldn’t because he was afraid of the state of exception. ‘We are prohibited from giving that out. Why would you take it out? It’s pointless,’ the man told me,” she said.

Then they assigned another lawyer to her, and she also refused to give the permission. The only hope she had was that he would be released during the initial hearing, but they told her they would hand it over when “he turns one year old,” which never happened.

“I went happily because they were going to give it to me,” narrates Marta, but unfortunately, it wasn’t true. Then they told her that they would give it when he turns two years old. Again, she arrived with the hope of receiving it, and nothing. Now they have told her to wait until August 2025. “Why do they lie?” questioned Delmy.

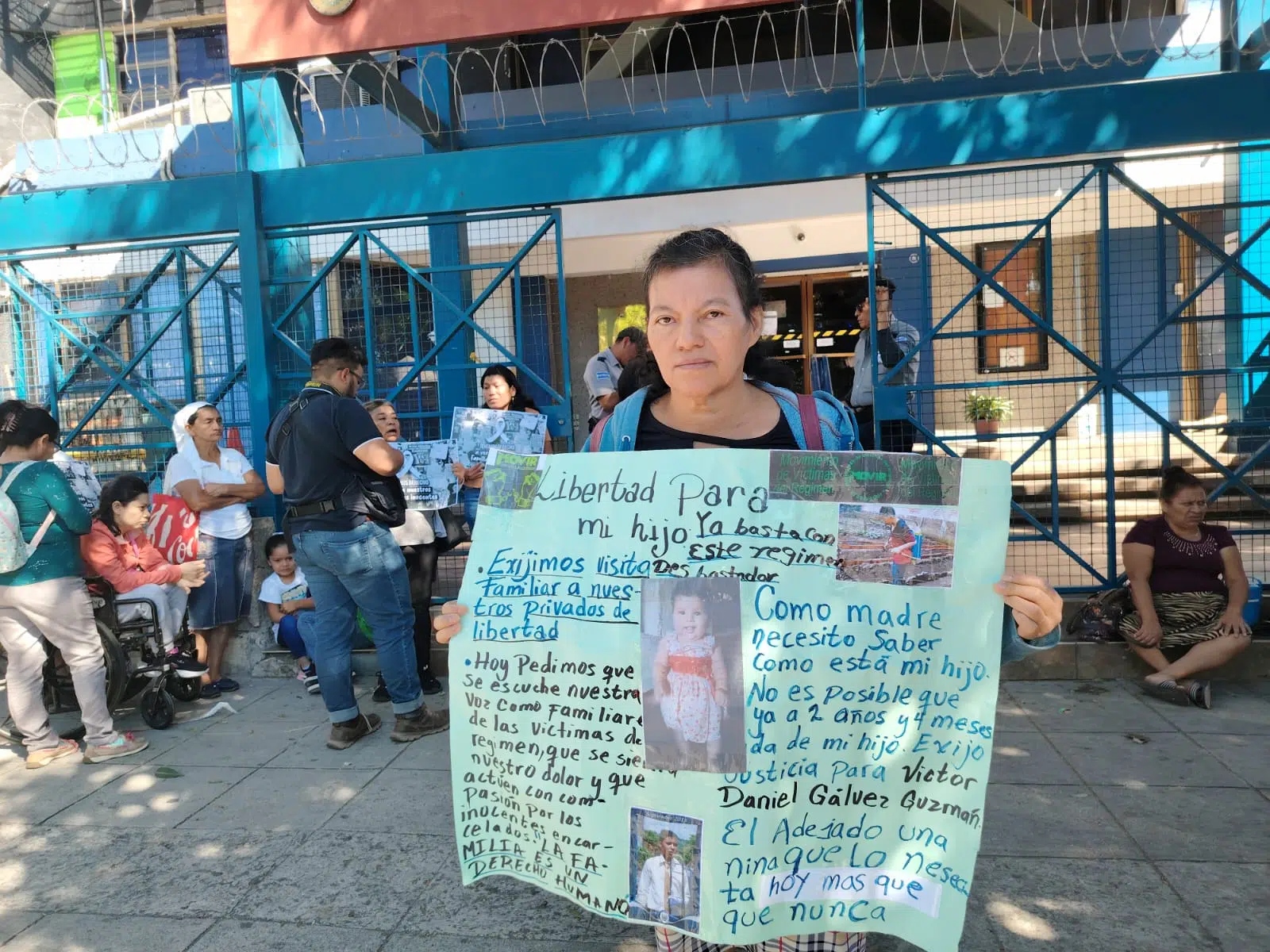

She demands her son’s freedom or at least to be allowed to visit him to know where he is. This is what the green sign she carries says, which she took to the offices of the Procuraduría General de la República (PGR) (Office of the Attorney General) last week.

Since her son was arrested on July 11, 2022, she has not found peace in her life because she doesn’t know if her son is alive or dead, if he is sick or malnourished. This uncertainty has undermined her health. She suffers from scleroderma, kidney, liver issues, and has diabetes.

But that is the least of her worries. She now wants to retrieve her granddaughter, who lives with her other grandmother. The little girl was one year old when her father was arrested. Delmy says the child is malnourished, but what worries her most is that she could be in danger because the woman is known “to sell her daughters.” Therefore, she went to the Consejo Nacional de la Primera Infancia, Niñez y Adolescencia (Conapina) (National Council for Early Childhood, Children, and Adolescents) to ask for help and for them to check on her granddaughter’s situation, but they have not yet done so.

“I already went there, to Conapina, to ask them to please help me with my granddaughter. I went to Mejicanos and they sent me to Santa Ana, then to Santa Tecla, and from there to Sonsonate. There they told me that they would call me, and to this date, they have not,” she reported.

Delmy says the government has always turned its back on her, and this would already be the third time. The second was the arrest of her daughter. But the first is an experience she will never forget. Her first daughter was taken from her when she was 19. It happened during labor when they took her out of her womb, and that was the only time she saw her. And although she asked the authorities for help, they never assisted her in searching for her, she lamented.

Delmy wasn’t the only mother who came to the Procuraduría to request permission for the records. Jeannete tried to obtain these documents online but was unsuccessful, as it required permission from the PGR. As such, she was sitting outside the institution’s offices waiting to be attended to. She hasn’t heard from her son since he was arrested in January of this year during the military encirclement set up in Tutunichapa.

What she regrets most is that her son didn’t even live in that community when he was arrested; he was just testing a motorcycle that a client had bought. He was riding in Tutunichapa when a soldier called him over to ask for his information. Even though he said he was there for work, he was captured. Now his mother demands to see him and is worried because she thinks they will never release him.

Las tres veces que el Estado le falló a Delmy

Delmy asegura que su hijo es inocente y solo podrá demostrarlo con los arraigos, una serie de documentos que no ha podido completar porque su abogada pública no le quiere entregar un permiso para que retire los antecedentes penales, en los cuales se demuestra que su hijo nunca ha tenido problemas con la justicia.

“Cuando fui a buscar al primer abogado de mi hijo, para pedirle una autorización para los antecedentes, me dijo que no podía porque tenía miedo al régimen. ‘Para nosotros está prohibido dar eso. ¿Para qué lo va a sacar? Es por gusto que lo haga’, me dijo el señor”, indicó.

Luego le asignaron a otra abogada y ella tampoco le quiso dar el permiso. La única esperanza que tenía era que lo liberaran cuando fue la audiencia inicial, pero le dijeron que se lo entregarían cuando “tuviera un año”, algo que no sucedió.

“Yo iba contenta porque me lo iban a dar”, relata Marta, pero lamentablemente era mentira. Luego le dijeron que cuando él tuviera dos años sí se lo iban a dar. Otra vez llegó con la esperanza que se lo dieran y nada. Ahora le han dicho que espere hasta agosto de 2025. “¿Por qué mienten?”, cuestionó Delmy.

Ella exige la libertad de su hijo o por lo menos que le permitan visitarlo para saber donde está. Así lo dice el cartel verde que carga y que llevó a las instalaciones de la Procuraduría General de la República (PGR) la semana pasada.

Desde que su hijo fue capturado el 11 de julio de 2022, ella no ha encontrado paz en su vida, porque no sabe si su hijo está vivo o muerto, si está enfermo o desnutrido. Esa incertidumbre ha socavado su salud. Padece de esclerodermia, de los riñones, el hígado y tiene diabetes.

Pero esa es la menor de sus preocupaciones. Ella ahora quiere recuperar a su nieta, que vive con su otra abuela. La pequeña tenía un año cuando su papá fue capturado. Delmy dice que la niña está desnutrida, pero lo que más le preocupa es que podría correr peligro, porque la señora tiene fama “de vender a sus hijas”. Por ello, fue al Consejo Nacional de la Primera Infancia, Niñez y Adolescencia (Conapina) a pedir que la ayuden y vayan a ver la situación de su nieta, pero aún no lo hacen.

“Ya fui ahí, al Conapina, a pedirles por favor que me ayuden con mi nieta, fui a Mejicanos y me mandaron para Santa Ana, luego a Santa Tecla, de ahí para Sonsonate. Allí me dijeron que me iban a hablar y hasta la fecha no lo han hecho”, denunció.

Delmy dice que el gobierno siempre le ha dado la espalda y esta ya sería la tercera vez. La segunda fue la captura de su hija. Pero la primera es un experiencia que jamás olvidará. Le robaron a su primera hija cuando ella tenía 19 años. Fue en la labor de parto cuando se la sacaron de su vientre y esa fue la única vez que la vio. Y aunque pidió ayuda a las autoridades nunca le ayudaron a buscarla, lamentó.

Delmy no fue la única madre que llegó a la Procuraduría a solicitar un permiso para los antecedentes, Jeannete, intentó sacar estos documentos en línea, pero fue imposible, dice, le pedía permiso de la PGR. Por ello, estaba sentada a las afueras de las instalaciones de la institución esperando ser atendida. Ella no sabe de su hijo desde que fue capturado en enero de este año, en el cerco militar instalado en la Tutunichapa.

Lo que más lamenta es que su hijo ni siquiera vivía en esa comunidad cuando fue capturado, sino que andaba probando una moto que había comprado un cliente. El recorrido lo hacía en la Tutunichapa y allí fue llamado por un militar para preguntarle por sus datos. Y aunque le dijo que estaba allí por trabajo, lo capturó. Ahora su madre exige verlo y está preocupada porque piensa que jamás van a liberarlo.