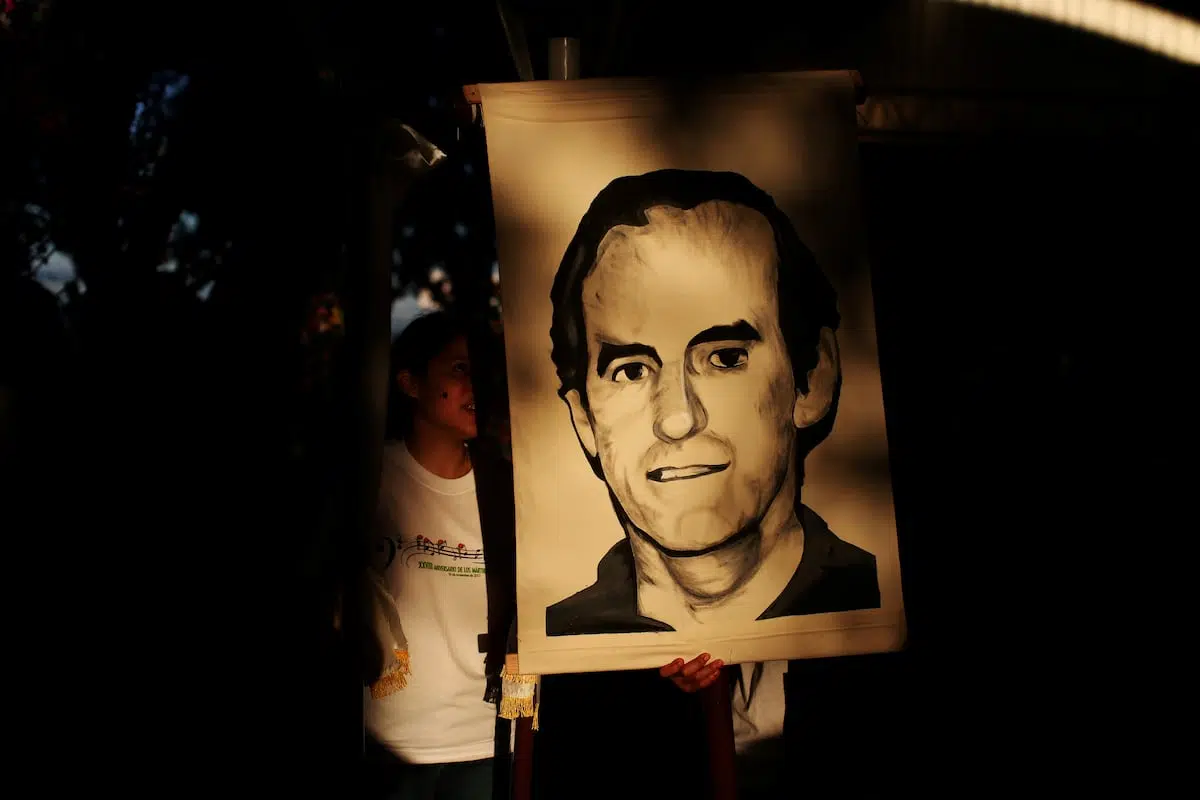

Activist Benjamín Cuéllar considers the Jesuit priest Ignacio Ellacuría as an “apostle.” Cuéllar was the director of the Human Rights Institute of the Central American University (Idhuca) that pushed the Salvadoran justice system to hold accountable the material and intellectual perpetrators of the massacre of five Spanish priests, a Salvadoran, and two women on November 16, 1989, on the university campus. Cuéllar is well-acquainted with the details of this process, which he began working on in 1992, and laments that the truth about that tragic event has not yet been established and that the victims have not received justice. Last week, a court in San Salvador opened a process against 11 individuals, including former President Alfredo Cristiani, three ex-military officers, and a former lawmaker, for being the intellectual authors of the crime. However, the activist lacks confidence in the Salvadoran justice system, which is controlled by the current president, Nayib Bukele, to have a real commitment to the case. Nonetheless, the continuation of this trial revives the image of a theologian and his colleagues committed to peace and reconciliation in a country torn apart by war. “It should be said that with Ellacuría, an apostle of Jesus Christ passed through El Salvador,” states Cuéllar. “He was a staunch promoter and defender of a negotiated resolution to the conflict,” he adds.

A conflict that left more than 70,000 dead, 80% of them civilians, and spanned from 1979 to 1992. These were terrible years when the Salvadoran army fought against the guerrillas of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), who wanted to establish a new socialist regime. The wealthiest sectors of the small Central American country feared losing their privileges, and there was a consensus among the influential families of the nation to eradicate the guerrillas. The civil war resulted in events that horrified the world, such as the assassination of Archbishop Óscar Arnulfo Romero on March 24, 1980, while officiating a mass in a chapel in the Salvadoran capital, an attack perpetrated by a far-right group, or the massacre of American missionaries in December of that same year, which according to an OAS report, “were brutally murdered and found with signs of abuse and torture.”

Salvadoran memory also holds the infamous El Mozote massacre, considered the worst military massacre in the Americas, carried out by soldiers of the Atlácatl Battalion of the Salvadoran army, many of whom were trained at the School of the Americas. At least 986 people were killed (552 children and 434 adults, including 12 pregnant women) in a bloodbath that spanned from December 10 to 12, 1981. Alongside them, the history of horror includes the murder of the UCA Jesuits. The events took place on the early morning of November 16, 1989, when an elite group of the Atlácatl Battalion stormed the university campus and shot dead six Jesuit priests: Spaniards Ellacuría, Ignacio Martín-Baró, Segundo Montes, Amando López, Juan Ramón Moreno, and Salvadoran Joaquín López. That night, they also killed the wife and daughter of the university’s gardener, Elba and Celina Ramos.

The army’s cruelty was such that Cuéllar recalls that in the United States, which for decades maintained a strategy to prevent the spread of communism in what its most conservative politicians considered Washington’s “backyard,” voices began to rise to end the bloodshed. “There was a U.S. senator who said he was ashamed to be funding an army that committed such atrocities,” comments Cuéllar. “The war was already being repudiated from all corners of the world,” adds the activist, whose cousin, Patricia Emilie Cuéllar Sandoval, her father, and the domestic worker went missing during the conflict, a case that led to a ruling in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

In that context of horror, the figure of theologian Ellacuría, then rector of the UCA, stands out as an important actor for finding a negotiated resolution to the war and declaring peace in the Central American country. The philosopher also defended Liberation Theology, which preached the Christian principle of a preferential option for the poor. It was a branch of Catholicism that aroused distrust among politically and economically conservative sectors in Latin America, as it was associated with left-wing currents attempting to impose socialist systems in the region. “By being a staunch defender of a negotiated resolution to the conflict, he was positioned as an ideologist of the FMLN and also for his significant contributions in favor of the popular majorities, the implementation of human rights, which he advocated to be applied the same way to a privileged minority and popular sectors,” Cuéllar explains in a phone interview from San Salvador.

Paolo Lüers, a political columnist and a witness and survivor of the Salvadoran tragedy, lives in Mexico and has published ‘Double Face: War, Peace, and War’, where he recounts his personal experiences as a reporter covering the civil war and, later, for 12 years as a guerrilla upon joining the FMLN ranks. He explains that his work in the guerrilla organization was related to communication within the so-called Radio Venceremos System, which included film production and international dissemination. Lüers was in New York on that fateful day in November as part of his dissemination work and remembers the impact that the news of the 1989 massacre had on him. “For me and the people I was in permanent contact with, it was horrible,” says Lüers. “Ellacuría’s loss was a significant and heartfelt loss for both the FMLN and President Alfredo Cristiani, because Ellacuría was the bridge in the peace negotiations. He always maintained open and trusting contact with both parties. The Front’s leadership had very open discussions with him. They trusted that they could tell him things that he would not reveal publicly. Everyone needed that contact,” the journalist affirms.

Lüers recounts in a phone interview that, when it became known that the guerrillas were organizing an offensive against San Salvador in November 1989 as a decisive blow against the army, Ellacuría made several efforts with the Front to persuade them not to carry it out. “Everyone speculated about it, but someone like Ellacuría had direct information that it was being planned and that it was going to happen soon. He did not agree. His recommendation was not to do it, as he feared that the peace process would be completely ruined. But the Front responded that they would carry it out in any case because the blow would increase the chances of peace, clearly demonstrating that the army would not win the war and that the only option for the government was to seek a negotiated resolution and make the necessary concessions,” Lüers remembers.

Lüers recalls that Ellacuría went with this information to speak with President Cristiani and informed him that the FMLN would not break off the negotiations. “This was extremely important so that no one would think that peace was impossible and bet everything on war,” he explains. Then the massacre occurred, and Lüers remembers what he thought in New York: “Everything was ruined. It was devastating. Besides, Ellacuría was a man who generated much respect and affection. We tried to do everything possible to make sure it did not have the desired effect. We first said that we were not responsible. And we did not point fingers at Cristiani, but at the army’s General Staff,” he narrates. After the massacre, negotiations continued, and on April 4, 1990, the Salvadoran Government and the FMLN signed the first commitment in Geneva to seek a resolution to the armed conflict, under the supervision of the United Nations.

Since then, the path to find justice for the priests and the two women murdered has been long and tortuous. The Salvadoran justice system prosecuted former Colonel Guillermo Benavides for this crime, sentencing him to 30 years in prison, while Spanish justice sentenced former Colonel Inocente Orlando Montano to 130 years in prison in 2020. The Spanish Prosecutor’s Office accused him of participating in the planning and execution of the plan to eliminate the victims. Last week, a judge in San Salvador ordered 11 accused of being the intellectual authors of that crime to stand trial, including former President Alfredo Cristiani, former military officers Joaquín Cerna, Juan Rafael Bustillo, and Juan Orlando Zepeda, former lawmaker Rodolfo Parker, and six other individuals.

Both Cuéllar and Lüers doubt that Cristiani knew about the massacre, as he was interested in the role that theologian Ellacuría played in the negotiations. “The political, theoretical, and logical conclusion is that Cristiani could not have had an interest in killing him because it was a powerful blow to him,” Lüers affirms. “There was a faction within the armed forces that wanted to sabotage the peace negotiations and decided to do so by killing Ellacuría. When many people on the left said that Cristiani ordered the assassination, I thought it was absurd, because it did not correspond to the relationship, the triangle that existed between the Front, Ignacio, and the president,” he asserts. Cuéllar recalls that in their accusation, they pointed out six high-ranking army officials for the intellectual authorship of the crime and President Cristiani for concealment and omission, for being part of the power apparatus. “He had the possibility of preventing that crime,” he explains. “Some say that he gave the order, but with everything I know about the case over this time, I am convinced that Cristiani did not give the order,” Cuéllar affirms.

Although Cuéllar and Lüers hope that the truth will be established, and justice will be served for the victims of the massacre in a court case awaited for decades, they do not trust the current Salvadoran justice system, heavily influenced by President Bukele’s control over the state apparatus. “It was an expected decision, but now what I want is that justice is not manipulated,” Cuéllar states. “There can be no trust in El Salvador’s judicial system, zero. And specifically in the judge chosen for this, Arroldo Córdoba Solís, who is a candidate for the Court of Accounts and is most likely seeking to earn points to be elected, but he is a judge completely subject to political instructions and acts in the hearings without taking into account even the minimum rules,” Lüers asserts. Despite these criticisms, it is now up to the Salvadoran justice system to move forward in a case that remains an open wound in this Central American country. “They eliminated a moral, political, and intellectual leadership,” Lüers concludes.

El martirio de Ignacio Ellacuría y los jesuitas de El Salvador: “Eliminaron un liderazgo moral, político e intelectual”

El activista Benjamín Cuéllar considera al sacerdote jesuita Ignacio Ellacuría como un “apóstol”. Cuéllar fue director del Instituto de Derechos Humanos de la Universidad Centroamericana (Idhuca) que impulsó en la justicia salvadoreña el caso para juzgar a los autores materiales e intelectuales de la masacre de cinco sacerdotes españoles, un salvadoreño y dos mujeres ocurrida el 16 de noviembre de 1989 en el campus de la universidad. Cuéllar conoce muy bien los detalles de este proceso en el que comenzó a trabajar en 1992 y lamenta que hasta ahora no se haya logrado imponer la verdad sobre aquel hecho fatídico y que las víctimas no tengan justicia. Un juzgado de San Salvador abrió la pasada semana un proceso contra 11 señalados, entre ellos el expresidente Alfredo Cristiani, tres exmilitares y un exdiputado, de ser lo autores intelectuales del crimen, pero el activista no tiene confianza en que la justicia salvadoreña, controlada por el actual presidente Nayib Bukele, tenga un compromiso real en el caso. La continuidad de este juicio, sin embargo, revive la imagen de un teólogo y sus colegas comprometidos con la paz y la reconciliación de un país destruido por la guerra. “Debería decirse que con Ellacuría pasó un apóstol de Jesucristo por El Salvador”, afirma Cuéllar. “Fue un férreo promotor y defensor de la salida negociada al conflicto”, agrega.

Un conflicto que dejó más de 70.000 muertos, el 80% de ellos civiles, y que se extendió de 1979 a 1992. Fueron años terribles, cuando el ejército salvadoreño combatió a las guerrillas del Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN) que querían imponer un nuevo régimen de carácter socialista. Los sectores económicos más poderosos del pequeño país centroamericano temían perder sus privilegios y había un consenso entre las influyentes familias de la nación por erradicar a la guerrilla. La guerra civil dejó hechos que horrorizaron al mundo, como el asesinato del arzobispo Óscar Arnulfo Romero el 24 de marzo de 1980 cuando oficiaba una misa en una capilla de la capital salvadoreña, un atentado perpetrado por un grupo de extrema derecha, o la masacre de misioneras estadounidenses en diciembre de ese mismo año, que según un informe de la OEA, “fueron brutalmente asesinadas y halladas con señales de vejaciones y torturas”.

La memoria salvadoreña también guarda la conocida como masacre de El Mozote, considerada como la peor matanza militar en América, y perpetuada a manos de militares del Batallón Atlácatl del Ejército salvadoreño, muchos de ellos formados en la Escuela de las Américas. Fueron asesinadas al menos 986 personas (552 niños y 434 adultos, entre ellos 12 mujeres embarazadas) en una sangría que se extendió del 10 al 12 de diciembre de 1981. Y junto a ellas se guarda en la historia del horror el asesinato de los jesuitas de la UCA. Los hechos ocurrieron la madrugada del 16 de noviembre de 1989, cuando un grupo de élite del Batallón Atlácatl irrumpió en el campus de la universidad y mató a tiros a los seis sacerdotes jesuitas: los españoles Ellacuría, Ignacio Martín-Baró, Segundo Montes, Amando López, Juan Ramón Moreno, y el salvadoreño Joaquín López. Esa noche también asesinaron a la esposa e hija del jardinero de la universidad, Elba y Celina Ramos.

La crueldad del Ejército había sido tal que Cuéllar recuerda que en Estados Unidos, que por décadas mantuvo una estrategia para evitar la expansión del comunismo en lo que sus políticos más conservadores consideraban el “patio trasero de Washington”, comenzaron a alzarse voces para terminar con aquella sangría. “Hubo un senador estadounidense que dijo que le daba vergüenza estar financiando a un Ejército que cometía ese tipo de atrocidades”, comenta Cuéllar. “La guerra ya era repudiada desde todas las partes del mundo”, agrega el activista, cuya prima, Patricia Emilie Cuéllar Sandoval, su papá y la trabajadora doméstica fueron desaparecidos durante el conflicto, un caso que logró una sentencia en la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos.

En ese contexto de horror, la figura del teológo Ellacuría, entonces rector de la UCA, destaca como actor importante para encontrar una salida negociada a la guerra y declarar la paz en el país centroamericano. El también filósofo era un defensor de la Teología de la Liberación que predicaba el principio cristiano de la opción preferencial por los pobres. Era una rama del catolicismo que despertaba desconfianza en sectores políticos y económicos conservadores de América Latina, porque la relacionaban con corrientes de izquierdas que querían imponer sistemas de carácter socialista en la región. “Al ser un férreo defensor de la salida negociada del conflicto, lo ubicaban como ideólogo del FMLN y también por sus aportes importantísimos a favor de las mayorías populares, la implementación de los derechos humanos, que no se vieran como simples tratados o textos, sino que se aplicaran de igual manera a una minoría privilegiada y a los sectores populares. Todo eso a partir de la realidad salvadoreña que él vivió”, explica Cuéllar en entrevista telefónica desde San Salvador.

Paolo Lüers es un columnista de temas políticos, testigo y sobreviviente de la tragedia salvadoreña. Vive en México y ha publicado Doble Cara: Guerra, paz y guerra, obra en la que relata sus vivencias personales como reportero cubriendo la guerra civil y, después, durante 12 años como guerrillero, tras unirse a la filas del FMLN. Explica que su trabajo en la organización guerrillera estaba relacionado con la comunicación, dentro del llamado Sistema Radio Venceremos, que incluía producción cinematográfica y difusión internacional. Lüers estaba en Nueva York aquel fatídico día de noviembre como parte de su trabajo de divulgación y recuerda el impacto que le generó la noticia de la masacre de 1989. “Para mí y para la gente con quienes estaba en contacto permanente fue horrible”, dice Lüers. “La de Ellacuría era una pérdida muy fuerte y sentida tanto para el FMLN como para el presidente Alfredo Cristiani, porque Ellacuría era el puente en las negociaciones de paz. Tenía siempre un contacto abierto y de confianza con ambas partes. La dirigencia del Frente tenía discusiones muy abiertas con él. Confiaban en que podían decirle cosas que él no revelaría en público. Todos necesitaban mucho de ese contacto”, afirma el periodista.

Lüers relata en entrevista telefónica que, cuando se supo que la guerrilla organizaba una ofensiva contra San Salvador en noviembre de 1989, como un golpe certero contra el Ejército, Ellacuría hizo varias gestiones con el Frente para convencerlos de que no la llevaran a cabo. “Se venía venir, todo mundo especulaba al respecto, pero alguien como Ellacuría tenía información directa de que se estaba planificando y de que iba a pasar pronto. Él no estaba de acuerdo. Su recomendación era que no la hicieran, porque tenía miedo de que el proceso de paz se iba a fregar de una vez por todas, pero el Frente le respondió que lo harían de cualquier manera, porque el golpe aumentaría las posibilidades de la paz, se iba a demostrar claramente que el Ejército no ganaría la guerra y que la única opción para el Gobierno era buscar de verdad una salida negociada y hacer las concesiones necesarias”, recuerda.

Lüers relata que Ellacuría fue con esa información a hablar con el presidente Cristiani y le informó que las negociaciones no se iban a romper de parte del FMLN. “Eso era sumamente importante para que nadie pensara que la paz era imposible y se apostara todo a la guerra”, explica. Luego ocurrió la matanza y Lüers recuerda lo que pensó en Nueva York: “Se cagaron en todo. Era gravísimo. Además, era un hombre que generaba mucho respeto y cariño. Tratamos de hacer todo lo posible para que eso no tuviera el efecto deseado. Dijimos primero que nosotros no fuimos. Y no señalamos a Cristiani, si no al Estado Mayor del Ejército”, narra. Tras la masacre, las negociaciones continuaron y el 4 de abril de 1990 el Gobierno salvadoreño y el FMLN firmaron en Ginebra un primer compromiso para buscar una salida al conflicto armado, bajo el seguimiento de las Naciones Unidas.

Desde entonces, el camino por hallar justicia para los sacerdotes y las dos mujeres asesinadas ha sido largo y tortuoso. La justicia salvadoreña ha procesado por este crimen al excoronel Guillermo Benavides, condenado a 30 años de prisión, mientras que la justicia española condenó en 2020 a 130 años de cárcel al excoronel Inocente Orlando Montano. La Fiscalía española lo acusó de participar en el diseño y ejecución del plan para acabar con las víctimas. La pasada semana un juez de San Salvador ordenó someter a juicio a 11 acusados de ser los autores intelectuales de aquel crimen, entre ellos el expresidente Alfredo Cristiani, los exmilitares Joaquín Cerna, Juan Rafael Bustillo y Juan Orlando Zepeda, el exdiputado Rodolfo Parker y otras seis personas.

Tanto Cuéllar como Lüers dudan de que Cristiani conocieran sobre la matanza, porque le interesaba el rol que jugaba el teológo Ellacuría en aquellas negociaciones. “La conclusión política, teórica, lógica es que no podía haber interés de Cristiani en matarlo, porque era un fuerte golpe para él”, afirma. “Había una fracción dentro de la Fuerza Armada que quería sabotear la negociación de la paz y decidió hacerlo matando a Ellacuría. Cuando mucha gente desde la izquierda dijo que Cristiani ordenó el asesinato, pensé que era absurdo, porque no correspondía a la relación, al triángulo que existía entre el Frente, Ignacio y el presidente”, asegura. Cuéllar recuerda que en su acusación señalaban a seis altos funcionarios del Ejército por la autoría intelectual del crimen y al presidente Cristiani por encubrimiento y omisión, por ser parte del aparato del poder. “Tenía la posibilidad de evitar ese delito”, explica. “Hay quienes dicen de que él dio la orden, pero con todo lo que conozco del caso durante este tiempo estoy convecidísimo de que Cristiani no la dio”, afirma.

Aunque Cuéllar y Lüers esperan que se establezca la verdad y haya justicia para las víctimas de la masacre en un proceso judicial esperado durante décadas, no confían en el actual sistema de justicia salvadoreño, fuertemente influenciado por el control que el presidente Bukele tiene del aparato estatal. “Era una decisión esperada, pero ahora lo que quiero es que no se manipule la justicia”, dice Cuéllar. “No se puede tener ninguna confianza en el sistema judicial de El Salvador, cero. Y en específico en el juez escogido para eso, Arroldo Córdoba Solís, que es candidato a la Corte de Cuentas y a lo mejor busca con esto ganar los puntos para que lo elijan, pero es un juez sometido totalmente a instrucciones políticas y que actúa en las audiencias sin tomar en cuenta las mínimas reglas”, afirma Lüers. A pesar de estas críticas, es el turno de la justicia salvadoreña para avanzar en un caso que es una herida abierta en ese país centroamericano. “Eliminaron un liderazgo moral, político e intelectual”, asegura el periodista Lüers.