“They’re stealing millions”…”They want to break my back, and the worst part is it’s people from my own side.”

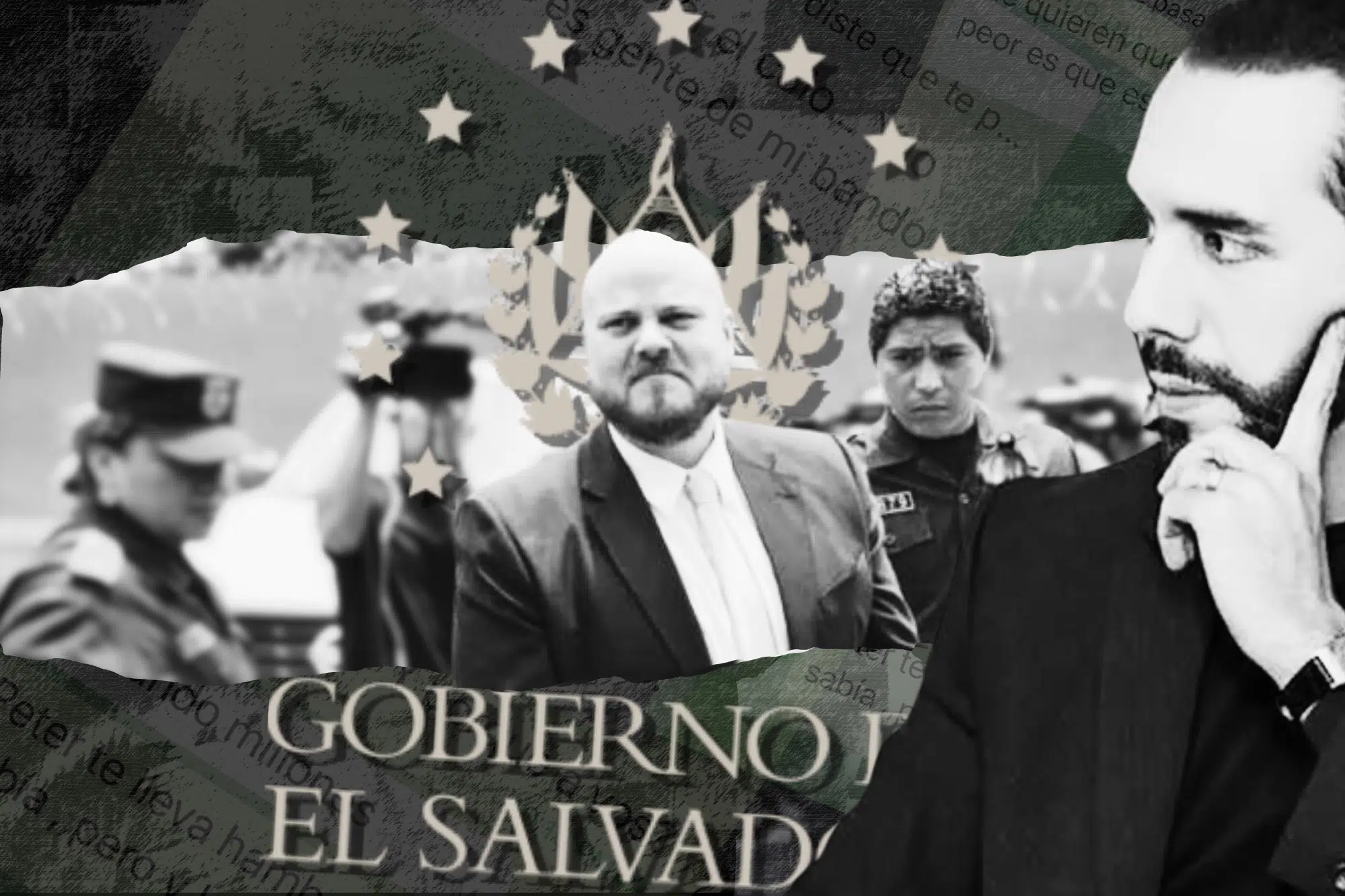

This special investigation reveals that Alejandro Muyshondt had access to President Nayib Bukele’s inner circle during the first two years of his initial presidential term (between 2019 and 2021). Muyshondt was aware of initiatives to spy on opponents and journalists and reported cases of corruption and suspicions that Bukele’s allies were linked to drug trafficking both within the government and to foreign officials. Ernesto Castro, the current president of the Legislative Assembly and then Bukele’s private secretary, asked him to set up a political espionage office.

Testimonies from people close to Muyshondt and recovered electronic messages indicate that Bukele’s public security advisor suffered mistreatment and inadequate medical care after being detained in August 2023. The medical records compiled from the time he was admitted to a public hospital, after allegedly being beaten, contain dozens of contradictions. The family suspects that Alejandro Muyshondt died, as suggested by signs found on the body, as a result of torture he may have received while in custody.

Alejandro Muyshondt knew too much. And he knew it early on when the government he worked for, led by President Nayib Bukele, was just beginning. Jus over seven months had passed since the new president’s inauguration in June 2019, and Muyshondt already knew that some officials, particularly in the security cabinet, had set up corruption networks from their offices; that the lawmaker recently appointed by Bukele as head of prisons was diverting funds from prison stores and creating phantom positions; and that another official lawmaker was involved in drug trafficking routes along the northern corridor of the country.

Jorge Alejandro Muyshondt Álvarez, a Salvadoran born on February 12, 1977, descended from a Belgian grandfather, and a specialist in informatics, was appointed national security advisor at the beginning of the new government. He was bonded to Bukele through a friendship that began after the founding of Nuevas Ideas, the new president’s party, and was strengthened after Muyshondt assisted the politician in navigating issues such as the “hacking” by a group of Bukele supporters in 2016 of La Prensa Gráfica, a critical newspaper, or when he helped bring down the website of Revista Factum, an independent media outlet that had just published a piece on the connection between Bukele and $1.9 million received from Alba Petróleos de El Salvador, a company accused of laundering Venezuelan oil money.

Once named national security advisor, Muyshondt worked on political intelligence and cybersecurity. In an office set up in Condado Santa Elena, on the outskirts of San Salvador, partly financed with money from the Presidential House, the advisor collected, among other things, information about the corruption that had become entrenched in the new government from the start.

Muyshondt also knew very early on that knowing these things and denouncing them could cost him his life. Because Muyshondt reported, first internally within the government and Nuevas Ideas, and then to state and foreign investigators.

“They want to break my ass, and the worst part is it’s people from my own side,” Muyshondt told one of his collaborators in WhatsApp messages. “You never know. I have no fear of dying. But if they screw me over… I’ll be the one laughing in my grave,” he wrote on February 14, 2020. The messages were a premonition: almost three years later, on August 9, 2023, the attorney general, appointed by Bukele, ordered Muyshondt’s arrest on charges of revealing official secrets and other offenses. Six months later, the national security advisor died in a state hospital after being admitted there with a head injury and a brain infection reportedly caused by a beating.

The person who received those WhatsApp messages in 2020 asked who the advisor suspected: “But who” would want to harm him? In response, Muyshondt mentioned the names of officials close to the president: “Rogelio, Peter, Osiris, Sanabria, etc.” Rogelio is Rogelio Rivas, then Minister of Justice and Public Security. Peter is Peter Dumas, a personal friend of Bukele and current director of the Organismo de Inteligencia del Estado (State Intelligence Agency, OIE). Osiris is Osiris Luna Meza, a former lawmaker of the Grand Alliance for National Unity (GANA) party appointed as head of the Dirección General de Centros Penales (General Directorate of Prisons) and honorary vice minister of security. Sanabria is Ernesto Sanabria, a close friend of the president, accused, among other things, of misogynistic violence and directing troll farms to harass journalists and opponents.

One of Muyshondt’s theses, as revealed in dozens of messages he sent to collaborators and close associates, was that a group from the GANA party, led by lawmaker Guillermo Gallegos and Luna Meza, had taken over Bukele’s security cabinet to enrich themselves. GANA was the political formation that Nayib Bukele ran for the presidency in 2019 after the Supreme Electoral Tribunal of El Salvador denied the registration of Nuevas Ideas, his party.

Over time, several investigations, especially one from the Fiscalía General de la República de El Salvador (FGR) (Attorney General’s Office of El Salvador) before Bukele took control of it, and another from the Vulcano Task Force of the United States, would prove Muyshondt right. Both offices collaborated for months in an investigation into corruption in the Bukele government, which would take shape by 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Before that, Alejandro Muyshondt had already warned of the corruption.

Those investigations bore fruit. Some were strengthened by the Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en El Salvador (CICIES) (International Commission Against Impunity in El Salvador), a supranational investigative entity funded by the Organization of American States (OAS), which Bukele initially supported but ended up closing when investigations reached his officials. Based on these investigations, prosecutors from the Southern District of New York, supported by Vulcano, prepared a criminal indictment against Osiris Luna, which was never filed in the appropriate court due to a political decision, according to a former official of Joe Biden’s administration in Washington.

Alejandro Muyshondt learned very early about this corruption.

When the COVID-19 lockdown was about to end, Muyshondt took his suspicion to the Presidential House, right to Nayib Bukele’s anteroom. In August 2020, the advisor met with Ernesto Castro, the president’s private secretary, warning him that drug trafficking and large-scale corruption were living within the government’s core.

Ibrajim Bukele, the president’s brother and one of his closest advisors, also heard Muyshondt’s complaints in a meeting that took place after the legislative elections of February 2021. The display of luxury items by officialist officials on social media, the advisor told Ibrajim, could come back to haunt them. “Lawmakers and mayors with new cars; if this isn’t taken into account, the project will erode,” said Muyshondt, who believed that everything good and bad that happened within the ruling party would be attributed to the president: “In Nuevas Ideas, everything revolves around your brother; people will not individualize the thefts.”

Prensa Comunitaria (Community Press) had access to 8 hours of recordings made by Muyshondt during conversations he had with Castro, with Ibrajim Bukele, with Xavier Zablah, president of the Nuevas Ideas party, with Minister of Security Gustavo Villatoro, and with Juan Pablo Durán, former president of the state-owned Banco de Desarrollo Social de El Salvador (Social Development Bank of El Salvador). Over six months, through digital comparisons between the recordings and public appearances of the officials and corroborations made with at least ten people who know them and have interacted with them, Infobae verified the authenticity of the audios.

Besides the audios, Prensa Comunitaria has in its possession hundreds of pages from Muyshondt’s medical file compiled at the Hospital Nacional Saldaña, where the former advisor was admitted at the end of September 2023, photos of the body taken by officials of the Instituto de Medicina Legal in San Salvador, and dozens of text messages exchanged via electronic messaging with people close to him. The authenticity of the texts was corroborated through interviews with former collaborators, relatives, officials in El Salvador and the United States, and specialists. Most spoke on condition of anonymity due to fear of reprisals from the Bukele government. Efforts were made to reach the officials and people mentioned in this investigation, but in most cases, there was no response; when there was a response, it is indicated.

What all these documents and interviews narrate is the story of a man who entered Bukele’s government to conduct political intelligence and work in cybersecurity, who became disappointed very quickly by what he saw within the new government, and who was frustrated by the inaction of the president—a man he admired. They also tell the story of how the Salvadoran State arrested him, mounted a criminal investigation against him, and watched him die after allegedly torturing him.

“In Asocambio there’s a huge mess, tiger”

Alejandro Muyshondt turns on his phone’s recorder before entering the office of Ernesto Castro, the private secretary of President Nayib Bukele, in the neoclassical building that houses the Presidential House in the southwestern part of the capital of El Salvador. He records everything, as he usually does whenever he meets with powerful government officials, his colleagues.

In this meeting, which takes place in August 2020, Muyshondt and Castro discuss threats to the presidency’s cybersecurity, corruption in the prison system, and the displeasure of the United States embassy with Guillermo Gallegos, a lawmaker and ally of Bukele whom federal agents in Washington have been tracking for drug trafficking since at least 2014.

Alejandro Muyshondt is 43 years old when he goes to this meeting at the Presidential House. A little over 18 months have passed since, partly as a thank you for everything he did for him in difficult times, Nayib Bukele appointed him national security advisor at the beginning of his first presidential term in June 2019. The president and the advisor are not close friends, but they have shared battles and details, like the time Muyshondt gifted him a Sig Sauer P226 Legion pistol. “I already have it in my hands. Thanks, ‘brother,’ for the gift. You outdid yourself,” Bukele thanked him on September 17, 2019, in a WhatsApp message accompanied by a photo of the gun.

These are not good times for Muyshondt when he meets with Castro. Since Bukele appointed him national security advisor, the president has not paid him much attention, and most of the requests he has made for his office—computers, more personnel, travel expenses for his bodyguards—where about 20 people work, often remain archived, many of them in the private secretary’s office. After long months of lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the advisor feels sidelined. But the conversation with Castro leaves him with some promises: the secretary commits to creating an additional position for his office, resolving some financial matters, and collaborating more closely with him.

From the beginning, Muyshondt has asked the private secretary for permission to speak “frankly, without fear of reprisals and dismissals.” Castro responds with a laugh. Frankly, the security advisor informs Bukele’s second-in-command at the Presidential House about a corruption scandal that is about to burst, the one involving ASOCAMBIO, an association created to manage money from prison stores controlled by Osiris Luna Meza, the director of prisons. Here is part of the conversation, which has only been edited for clarity (the original audio is available):

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “In ASOCAMBIO there’s a huge mess, tiger. Big-time stealing. They got rid of Jesús de la O, but the mistress is still there. And the Prosecutor’s Office is assembling a file on that crap. Osiris’s (Luna) mom started assembling certain supplier groups: ‘you give me the tamales, and you give me whatever’ and there’s always a commission (of money) in between. This person, with Jesús de la O, was part of that scheme; (the prosecutors) have conversations, they have a ton of stuff that the Prosecutor’s Office could take into account. They suddenly got a load of cash… That crap (the independent newspaper) El Faro also has clues about that…”

- Ernesto Castro: “…They already have them pegged.”

- Muyshondt: “And that’s a bomb that could be very counterproductive if it goes off before the elections. It’s a punch that’s well documented and hard to deny and create a smokescreen to dodge such a punch…”

- Castro: “Yes.”

“Osiris’s mom” is Alma Yanira Meza. Shortly after this conversation, two Salvadoran media outlets make public documents that prove the irregular diversion and use of USD 8.5 million in the prison system. The FGR, in fact, has an open case that is not public at the time and has named Luna and his mother as the main suspects in the diversion. Prosecutors also believe that mother and son are leaders of a corruption network that has created phantom positions to pocket unpaid salaries and awarded contracts for services in prisons in exchange for kickbacks. In a few months, thanks to these positions, the Luna Meza network has gained approximately USD 300,000, according to the prosecutor’s investigations.

The prosecutor’s files also show that Jesús de la O, the man Muyshondt refers to in his conversation with Castro, is the main executor of the irregular collections.

By 2020, the Prosecutor’s Office is also investigating Luna for his role in negotiating a governance pact with the MS13 and Barrio 18 gangs, which is then in effect. The Vulcano Task Force, created by the Donald Trump administration in Washington to support the anti-corruption fight in Central America, collaborates with the investigations into Luna Meza. At the end of 2021, when Joe Biden is already the president of the United States, the Department of State and the Treasury Department sanction Meza and his mother and accuse them of corruption. In Bukele’s San Salvador, nothing happens.

When, in the August 2020 meeting, Muyshondt informs the private secretary about the corruption network in prisons, Castro writes down the name of someone, one of the supposed individuals involved in the crimes, and moves on to something else. To this day, despite being one of the first major corruption scandals to hit the Bukele government, the main suspect remains in his position. When Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas lawmakers, the ruling party, appoint a loyal attorney general in May 2021, the investigations into Luna Meza and his mother are buried.

The silence and inaction only increase Muyshondt’s frustration, which had begun in late 2019 when he was already talking about these things to people close to him. “They’re stealing millions,” the security advisor wrote to one of his contacts on February 14, 2020. The day after, in an electronic diary where he logs the most relevant events of each day—a portion of which Prensa Comunitaria accessed—Muyshondt writes: “Now I understand why, despite being offered the OIE (State Intelligence Agency) it wasn’t ultimately given to me. Obviously, they need someone to cover all the shady stuff they’re doing in CAPRES (Presidential House). For that same reason, they have me isolated.”

The dynamic of the meetings that Alejandro Muyshondt holds with Bukele officials, between August 2020 and March 2021, is similar. The security advisor usually starts with requests for support for his office and the work he does. Then, he expands on what he has done and offered the government in areas like cybersecurity and technology and complains about the little attention he, his office, and his proposals receive. Amid the conversations, Muyshondt always introduces his concern about what he collects through his intelligence work on corruption and his analysis of the potential harm it can bring to the president. Never, in these conversations, do the officials dismiss the allegations against individuals such as Osiris Luna or Guillermo Gallegos, but neither do they say they will do anything about it.

“They’re questioning N’s friendship with Gallegos”

When speaking with Bukele’s private secretary in 2020, Alejandro Muyshondt addresses a recurring topic in other conversations, that of lawmaker Guillermo Gallegos, a man the United States has been investigating since 2014 for suspected drug trafficking ties, as confirmed by two officials from the Department of Justice in Washington to Prensa Comunitaria.

In 2020, Gallegos is a lawmaker who has been in Congress for 20 years, initially representing the right-wing ARENA party. Over time, along with other political operators discarded by traditional Salvadoran conservatism, he founded the Great Alliance for National Unity (GANA). In 2019, after several shifts in political loyalties, Gallegos and GANA lent the party to Bukele to run for the presidency, after failing to register Nuevas Ideas on time. Since then, Bukele and Gallegos have been friends, good friends.

In the 2020 conversation with Muyshondt, Secretary Ernesto Castro confirms the friendship ties. “That one (Gallegos) is a good buddy (friend) of Herbert (Saca) and a good buddy of Nayib,” says the official. Herbert Saca, the other person mentioned in the conversation, is the cousin of former President Antonio Saca, who is imprisoned for corruption offenses. Herbert has been accused of alliances with the drug trafficking group Los Perrones, one of the most significant in the history of Salvadoran organized crime, and of assisting previous governments—besides that of his cousin—in bribing lawmakers.

Gallegos faces several public accusations, including investigations by Salvadoran judicial authorities. In 2018, an examination by the Supreme Court of Justice’s (CSJ) Probity Section, the office that investigates officials’ asset growth, determined that Gallegos used approximately USD 100,000 irregularly and exchanged money with Adolfo Tórrez, another political operator who, like Herbert Saca, had ties to drug traffickers Los Perrones. Two investigations by El Faro newspaper also reveal that Gallegos claimed expenses for trips to Spain he never made and diverted half a million dollars from the Legislative Assembly to an NGO where his wife was a director. When Nuevas Ideas, Bukele’s party, gained a majority in the Legislative Assembly in February 2021, their lawmakers set up a committee to investigate legislative fund allocations to civil organizations; those financed by Gallegos were not touched.

But Gallegos’s primary problem has never been in El Salvador, where he has always emerged unscathed from investigations, but in the United States. The Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) has been tracking the former Salvadoran lawmaker since at least 2014 for potential drug trafficking links. Prensa Comunitaria spoke with a special agent from the FBI and a former U.S. diplomat stationed in El Salvador during those years; both confirmed the investigations.

By 2016, three years before Bukele became president, a court in New York’s Southern District (SDNY) had already opened a formal investigation into Gallegos. That year, when he was not yet working for Nayib, Alejandro Muyshondt traveled to the SDNY headquarters in Manhattan to discuss, among other things, Guillermo Gallegos, whom he knew well: Muyshondt had been active in GANA, the former lawmaker’s party.

In 2020, Muyshondt tells Castro, a CIA station agent in San Salvador had once again asked questions about Gallegos, and this time about his relationship with the newly elected President Bukele.

“There’s an ongoing case in the SDNY where (Guillermo) Gallegos is very involved and there’s this DEA prosecutor named Eric Stouch, and they have an obsession with Gallegos, you could say… I don’t care about Gallegos, what bothers me is… the person in charge of intelligence for the United States is questioning why N is friends with Gallegos. She asks why, if he’s made him a partner or if he’s covering for him,” Muyshondt warns the private secretary. At one point, Castro tries to downplay Gallegos’s relationship with Bukele but then acknowledges that both men are friends. Part of the conversation:

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “It worries me.”

- Ernesto Castro: “But N doesn’t have a strong friendship with Gallegos…”

- AM: “That’s not what N conveys…”

- EC: “I mean, yes they are friends, but a friendship… Like who? Well, like with Herbert (Saca), it feels the same to me.”

- AM: “I’m just telling you, be very careful with that stuff.”

- EC: “Yes, yes… Actually, I tell you, for me, that one (GG) is good buddies with Herbert and is good buddies with Nayib.”

- AM: “I’m also buddies with H.”

- EC: “I know, so am I… The point is…”

- AM: “The thing is that this could severely impact his (Bukele’s) image… Gallegos, the more he boasts about his friendship with that one (Bukele), the more popularity, the more votes.”

- EC: “He’s been clever, hasn’t he?”

The Americans, Muyshondt tells Castro, perceive that Bukele is protecting Gallegos. “It’s concerning how the Americans are already questioning whether that son of a bitch Gallegos is in partnerships with N or if N is protecting him,” he comments. The national security advisor’s alarm is justified: for years, Washington has suspected Gallegos of having alliances with local drug trafficking and moving large sums of money through foreign banks. The private secretary, in fact, knows something about all that.

Castro acknowledges that the State Intelligence Agency (OIE) sent him and Bukele a report containing compromising information about Gallegos. The secretary implies that nothing was done about it. “During the campaign… OIE gave us a report, but a stunning one, showing account movements abroad… And I still remember saying… Look… and what do we do with this crap… Nothing, let’s leave it there, let them keep searching, we don’t give a damn,” says the secretary.

Muyshondt is quite vocal about his concerns regarding Guillermo Gallegos. The same warning he brings to Ernesto Castro’s office, he repeats, more or less, in other meetings with officials close to Bukele. He tells Ibrajim Bukele, the president’s brother and main economic and commercial advisor, and Xavier Zablah, Nayib’s cousin and president of the Nuevas Ideas ruling party. Both listen and opt to remain silent.

The day Alejandro Muyshondt is captured in San Salvador, in an investigation the Bukele-appointed prosecutor opens based solely on two notes published in fake news outlets run by a government propagandist, the president details the accusations against his national security advisor on his social media. One of the alleged crimes, the president states before the Prosecutor’s Office makes a formal announcement, is the revelation of official secrets shared with journalists and “a foreign government.”

Alejandro Muyshondt has, indeed, talked to the Americans. It’s part of his job. The president’s inner circle knows it, among other reasons, because Muyshondt has told them himself when discussing the investigations on Gallegos. He has shared this information, among others, with Private Secretary Castro, Ibrajim Bukele, the brother, and Xavi Zablah, the cousin of the president and head of the Nuevas Ideas party. This is part of one of the conversations with Zablah recorded on Muyshondt’s phone:

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “I’ve been working with DEA… the intelligence chief has told me: either your president is protecting Gallegos or your president is with Gallegos…”

- Xavier Zablah: “I know, and we know…”

- AM: “Hopefully, that guy starts distancing himself because it’s going to cost us a big political price…”

- XZ: “I know.”

- AM: ”Look, the gringos have lots of dirt on Gallegos, so much so that in the USDNY (Southern District of New York prosecutor’s office) he has a big file… They’re doing it blatantly, they’re dropping off at San Juan La Herradura… When they seized USD 1.2 million in drugs, who was the one who jumped? Gallegos jumped and called the ‘chele’ (fair-skinned, Mauricio) Arriaza (Chicas, head of the Police), threatening to remove him…”

- XZ: “Look, I about those issues, man…”

A top police chief who collaborated in the past with Mauricio Arriaza Chicas, the director of the Policía Nacional Civil (PNC) (National Civil Police) appointed by Nayib Bukele, confirms that, on at least two occasions, Gallegos calls Arriaza and, in one of them, refers to a drug seizure. “You guys already screwed it up; you’re not making seizures, you’re hijacking because the merchandise was being sold by Torero (an unspecified alleged drug trafficker) and the ‘chapines’ (Guatemalans) who were paying USD 6,000 per kilo were smuggling it out through blind spots,” the lawmaker reportedly said, according to this officer.

Conversations and text messages shared with one of his collaborators reveal that from at least mid-2020, the security advisor meets with two Department of Justice agents assigned to the Vulcano Task Force, sometimes outside the country, in places like Panama City, Madrid, Guatemala City, Miami, and even France. Two officials working with Joe Biden’s administration in Washington confirm this relationship, as does a former member of the Salvadoran Public Ministry who was in contact with Vulcano.

“Our bad guys should be our bad guys”: Project C815 to Spy on Journalists and Opponents

When he meets with Ernesto Castro in August 2020, the presidential private secretary entrusts Alejandro Muyshondt with a particular mission. He asks him to set up a political espionage office, a center for intelligence, Castro calls it.

The idea takes shape over two meetings. In the first, where they also discuss lawmaker Gallegos, Castro explores the possibility of the national security advisor setting up a clandestine operation from his office to gather information on persons of interest. He asks for a short-term project proposal. The conversation begins as follows:

- Ernesto Castro: “Are you doing intelligence work?”

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “Yes, even when not assigned, I do. In fact, it’s one of the topics I want to discuss with you…”

When the conversation takes place, entering the second year of Nayib Bukele at the helm of the Executive Branch, the president governs without political correlation in the Legislature. Bukele has emerged relatively unscathed from the coronavirus crisis: he was among the first to close his country in March 2020, he constructed a hospital exclusively for treating those affected by the disease, and implemented an efficient vaccination policy. Later, the World Bank would say that Bukele concealed the actual death toll, and local media would publish investigations questioning the effectiveness of the COVID-19 hospital. But that would be later. Currently, Bukele’s men are preparing for the first legislative election and want to gain a majority in the Assembly. The president’s private secretary wants more information. That’s what he requests from Alejandro Muyshondt. The conversation continues:

- Ernesto Castro: “And how do we set up political intelligence?”

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “It can be done, but without formalizing it…”

- EC: “Mmmjm.”

- AM: “You can’t make it official, you know?”

- EC: “No.”

- AM: “Now, I tell you, these would be clandestine services.”

- EC: “Chocolate and vanilla popsicles… And what scope would it have?”

- AM: “Depends on what you want to do… Do you want to hack emails? Hack Facebook… That’s what is done, and from there, you can also provide tracking, with tracking it’s another thing.”

- EC: “Could you make a small project? When I say small, I mean a couple of guys, okay? And if we see that crap is giving us information and it’s worth it… For when…?”

- AM: “The people for already… There are certain things better not have them here: a server is rented in the Netherlands, let’s say, and from there the attacks are made, or Ukraine. Never did it with own servers, always paid to have the processing power there in another place.”

What follows is Castro asking Muyshondt for a meeting soon to review the project and make a decision. They arrange to meet a week later, and they do. The national security advisor arrives at the second meeting accompanied by Raúl Torres, an IT engineer and his trusted man. The two men enter Ernesto Castro’s office. Like the previous time, Muyshondt has his cell phone recorder on.

Upon entering, Muyshondt introduces Torres and provides a brief “background” of his assistant. Torres was, says the advisor, the one who helped him take down the Revista Factum website in 2019, the media that in September of that year revealed that Nayib Bukele had received USD 1.9 million from Alba Petróleos at the start of his political career when he was the mayor of Nuevo Cuscatlán. Alba Petróleos is the Salvadoran subsidiary of Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), a conglomerate of companies through which, according to U.S. and Salvadoran prosecutors, millions of dollars were laundered.

Muyshondt claims the intervention in Factum was executed by a direct order, although it’s unclear from the audio by whom. “When Factum started attacking us, we took down Factum for almost three weeks… Well, the order came directly from… to take down Factum, and we did it with few resources.” The editors of this media, according to what they published in 2020, confirmed it was offline for one week in October 2019, following the report linking Bukele with Alba Petróleos. A later investigation by the media determined Raúl Torres was implicated in the attack on the magazine.

In the talk with Ernesto Castro, Muyshondt says doing the same with bigger newspapers, like El Diario de Hoy or La Prensa Gráfica, is more difficult. The private secretary clarifies that’s not what interests him, his interest lies in listening to specific journalists. Here’s part of the conversation:

- Ernesto Castro: “We don’t give a damn to ‘hack’ El Diario de Hoy.”

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “But it can be done…”

- EC: “It’s the again journalists we intervene… that is totally different… Ehhh… We’re not taking down El Faro… Those things are mischievous, right? Mess with them and keep them off for a week, whatever… But the interesting part is intervening with… Carlos Dada… those guys…”

- AM: “But that’s easy.”

- EC: “Well, let’s do it, then…”

Before in the conversation, it was Torres who outlined what the political espionage office, termed project C815 by Muyshondt, would be responsible for. He explained to Castro that the first step would be to try accessing electronic devices and email accounts of subjects of interest through a method known as “phishing”, involving sending deceptive links so the person inadvertently grants access to their information.

Torres also laid out the objectives. The information collected, he said in the meeting, would be used “to set up campaigns, to cut off journalists’ communication with their sources, and to know when a report is being assembled.” The government’s major problem, Torres pointed out, was the “leakage” of documents.

Before Castro gave the go-ahead for the project, Alejandro Muyshondt asked for communication regarding the project to be compartmentalized, excluding other intelligence entities like the OIE, which the security advisor didn’t hold in high regard. Here’s part of that conversation:

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “Will this be managed by you and me and the president, or…?”

- Ernesto Castro: “Yes.”

- AM: “Because I wouldn’t feel comfortable working with more people.”

- EC: “The thing is, I want to understand exactly what this is so as not to step… on the other’s functions as well…”

- AM: “And what do the others do, dude?”

- EC: “Not much, they do a couple of little things there…”

- AM: “I’ve seen the reports, tiger, they’re laughable… You’ll say… it’s a nest of infiltrators you have there.

- EC: I do believe that, too…

- AM: They are not people loyal to the president; they are loyal to their paycheque.

- AM: The fewer people involved in this…

- EC: No, sure, this won’t be shared with anyone at all.

Before wrapping up the conversation and after Muyshondt and Castro reviewed some details on possible hiring and administrative needs of the project, the private secretary circled back to the central objective of this initiative: to provide Nayib Bukele with information on journalists and opponents, collected illegally, which could have utility for the president. In passing, Castro criticizes the OIE for losing focus by gathering information on people assumed to be allies of the government and the Presidential House.

“It doesn’t matter… Our bad guys should be our bad guys, we’ll figure out how to manage them later, but the outsiders who want to screw us… are the ones we need to see. We need to see what Neto Muyshondt (then-mayor of San Salvador for the opposition ARENA party and cousin of Alejandro who has been imprisoned for over three years) … And what Norman Quijano (former San Salvador mayor for ARENA, accused of alleged pacts with gangs and fugitive) does… or Rodolfo Parker… By doing this, we can have numerous elements to make the man happy, things he needs,” Ernesto Castro concludes.

The Final Fight and the Arrest

After those conversations, Alejandro Muyshondt’s presence in public is intermittent. Privately, he continues to send reports to his boss, the president, periodically. One of the last ones is dated February 2023. Muyshondt titles it “Retos 2023” (Challenges 2023), listing, among others, corruption: “There are several bad actors within the government.” Judging by communications with a collaborator during those days, it’s unlikely that President Bukele reads the reports; he doesn’t reply to any in writing, at least.

Despite the president’s silence, Muyshondt remains a person with open communication lines to Nuevas Ideas lawmakers and some of Bukele’s closest advisors, such as Sofía Medina, the communications secretary, and Sara Hannah, a Venezuelan who advises the president in various matters like international politics, state finances, or communication strategies. He exchanges WhatsApp messages with Hannah, who in November 2022 urges him to cease public accusations against Banco Agrícola de El Salvador regarding an issue in the electronic banking system which Muyshondt has echoed on social media.

His exchanges with Sofía Medina cover various topics, including Muyshondt’s public confrontations on social media with government and presidential officials. In May 2023, one of these arguments discussed with Medina marks the beginning of the final stretch in Alejandro Muyshondt’s life.

On May 9, 2023, Muyshondt accuses Ernesto Sanabria, the presidential press secretary, of corruption on his social media. He claims that Sanabria, one of Bukele’s closest men until then, spent USD 77,193 on clothes in 11 months with an annual income of USD 72,000. A WhatsApp conversation with Sofía Medina, who, according to two officials consulted, is Sanabria’s political adversary, reveals she was aware of the accusations against him and that Muyshondt was given an order to air all that information.

Medina, in her conversation with Muyshondt about Sanabria, does not deny the accusations against the press secretary, rather confirms that there were superior instructions.

By July 2023, more public accusations emerged. Muyshondt claims on social media that Erick García, an officialist lawmaker, is linked to drug trafficking. The accusation against García causes a minor earthquake and a heated exchange on social media with government officials. More allegations by Muyshondt follow. He accuses Christian Guevara, the head of Bukele’s majority bloc in Congress, of benefiting from state contracts. Guevara responds by saying that Muyshondt attempted to extort him. Again, Sofía Medina intervenes, the communications secretary and one of the most influential officials at the Presidential House.

In an August 2, 2023 conversation, Medina reprimands Muyshondt via WhatsApp after he released information about supposed corruption involving Guevara. Here’s part of the conversation conducted through messaging:

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “Seriously, Sofi, I haven’t messed with him (Guevara)… Sanabria’s, P(orfirio) Chica’s, and (Christian) Guevara’s trolls are already active.”

- Sofía Medina: “And why didn’t you say this before the primaries? If it was about cleaning up, it would’ve been good to know all these things earlier… By fighting with everyone, they’ll all fight with you, I’ve always supported you, but I feel you’re not thinking, nor reasoning. I understand your anger with Sanabria, but it seems like you want to take it out on everyone else.”

- AM: “If they want it, that’s fine, just tell me, we’ll come to an agreement and…”

Shortly after these discussions, Alejandro Muyshondt is detained at a police checkpoint located between San Salvador and San Juan Opico, on the outskirts of the capital. Just hours after the arrest, announced on social media by the Attorney General’s Office, President Nayib Bukele posts a lengthy explanation about it on his social networks. Muyshondt, the president says, is imprisoned because he revealed official secrets to journalists and “a foreign government,” and because he allegedly aided in the evasion of a corruption-accused individual, namely the former president Mauricio Funes. In its formal accusation, the prosecutor’s office will also say that Muyshondt revealed Bukele’s location at a certain moment, endangering the president’s life.

Muyshondt and Bukele had touched on the subject of Funes, a fugitive in Nicaragua since 2016 after being accused of several corruption acts during his government. In a screenshot, Muyshondt sent a conversation with Bukele to a collaborator in November 2019, in which the president asked for Funes’s phone number. In another conversation, where Bukele reprimands him for attacking Osiris Luna on social media, he also questions him for giving “information to Funes.” Muyshondt replies: “I have not spoken with Funes since I got his phone number when you asked me.”

One of the last electronic message exchanges Muyshondt had before his capture on August 9, 2023, was with Walter Araujo, a former lawmaker and former president of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, who, after shifting political allegiances multiple times and joining Herbert Saca and Guillermo Gallegos’s GANA party, has resurfaced as a spreader of fake news and a defender of Bukele and his government on opinion shows and official platforms.

In that discussion, Araujo accuses Muyshondt of what the attorney’s office will later formally charge him with: “leaking” the president’s location, something the security advisor denies in the chat. Muyshondt further reiterates to Araujo that his communication with Funes occurred because Bukele requested the former president’s phone number: “Ask the president (Bukele) when he asked me for Funes’s new number (I don’t know why, I didn’t question), but that’s why I had to contact Funes years ago.”

The night when police arrest Alejandro Muyshondt, the police and the prosecutor’s office also raid at least three homes of the security advisor’s relatives, including his office. Muyshondt’s relatives have confirmed these raids, during which prosecutors seized “tablets,” TVs, laptops, and phones, searching, says one who was at one raid, for codes to access virtual files in which Muyshondt might have stored information.

At one of the houses, where Muyshondt’s daughter and ex-partner live, Minister of Security Gustavo Villatoro shows up; while the office raid is led by Attorney General Rodolfo Delgado. They all pursue the same goal: the information, presumably left by the President Nayib Bukele’s national security advisor.

Long before his arrest, Alejandro Muyshondt suspected they wanted to kill him because of what he knew; he knew it early, in 2019, when Bukele’s government was just beginning. Later, when his confrontations with some officials he accused of corruption became public, and after months of sharing information about that corruption within the government and with American agents, it was Washington officials who warned him to leave El Salvador. “They told him six weeks before… that the president knew, it wasn’t safe for him,” said a collaborator about the Americans’ warning, confirmed in Washington by two Joe Biden administration agents. But he didn’t leave. He was captured. Eight months after entering a police station in San Salvador in good health, Alejandro Muyshondt died after experiencing a rapid deterioration that caused brain hemorrhage.

Listen to the second recording:

Listen to the next conversation:

Prensa Comunitaria: https://prensacomunitaria.org/2024/09/el-salvador-alejandro-muyshondt-el-asesor-de-nayib-bukele-que-supo-demasiado-y-termino-muerto/

El Salvador: Alejandro Muyshondt, el asesor de Nayib Bukele que supo demasiado y terminó muerto

“Están robando millones”…“Me quieren quebrar el culo y lo peor es que es gente de mi bando”

Esta investigación especial revela que Alejandro Muyshondt tuvo acceso al círculo íntimo del presidente Nayib Bukele durante los dos primeros años de su primer periodo presidencial (entre 2019 y 2021), que conoció de iniciativas para espiar a opositores y periodistas y que denunció, a lo interno del gobierno y ante funcionarios extranjeros, casos de corrupción y sospechas de que aliados de Bukele estaban vinculados al narcotráfico. Ernesto Castro, actual presidente de la Asamblea Legislativa y entonces secretario privado de Bukele, le pidió montar una oficina de espionaje político.

Testimonios de personas cercanas a Muyshondt y mensajería electrónica recuperada indican que el asesor de seguridad pública de Bukele sufrió malos tratos y deficiente atención médica después de ser detenido en agosto de 2023. El expediente médico levantado desde que fue ingresado a un hospital público, tras presuntamente ser golpeado, tiene decenas de contradicciones. La familia sospecha que Alejandro Muyshondt murió, según sugieren indicios encontrados en el cadáver, como consecuencia de torturas que pudo haber recibido cuando estuvo preso.

Alejandro Muyshondt supo mucho. Y lo supo pronto, cuando el gobierno para el que trabajaba, el del presidente Nayib Bukele, apenas arrancaba. Habían pasado poco más de siete meses desde la toma de posesión del nuevo mandatario, en junio de 2019, cuando ya Muyshondt sabía que algunos funcionarios, sobre todo en el gabinete de seguridad, habían montado redes de corrupción desde sus oficinas, que el diputado suplente al que Bukele acababa de nombrar jefe de prisiones desviaba fondos de las tiendas carcelarias y creaba plazas fantasmas y que otro diputado oficialista estaba implicado con las rutas del narcotráfico en el corredor norte del país.

Jorge Alejandro Muyshondt Álvarez, salvadoreño nacido el 12 de febrero de 1977, descendiente de un abuelo belga, especialista en informática, fue nombrado asesor nacional de seguridad al inicio del nuevo gobierno. Lo unía a Bukele una amistad que nació tras la fundación de Nuevas Ideas, el partido del nuevo presidente, y se había fortalecido luego de que Muyshondt le colaboró al político con asesoría informática para sacarlo de líos, como el provocado por el “hackeo” que un equipo de bukelistas hizo en 2016 a La Prensa Gráfica, un periódico crítico, o como cuando en septiembre de 2019 ayudó a tumbar el portal de Revista Factum, un medio independiente que acababa de publicar la relación entre Bukele y 1.9 millones de dólares que le había entregado Alba Petróleos de El Salvador, una empresa señalada por lavar dinero del petróleo venezolano.

Desde que fue nombrado asesor de seguridad nacional, Musyhondt trabajó en inteligencia política y en ciberseguridad. En una oficina montada en Condado Santa Elena, en las afueras de San Salvador, financiada en parte con dinero de Casa Presidencial, el asesor recogía, entre otras cosas, información sobre la corrupción que, desde el principio, se enquistó en el nuevo gobierno.

También supo Muyshondt muy pronto que conocer aquello y denunciarlo le podía costar la vida. Porque Muyshondt denunció, primero al interior del gobierno y del partido Nuevas Ideas, y luego a investigadores estatales, salvadoreños y extranjeros.

“Me quieren quebrar el culo y lo peor es que es gente de mi bando”, dijo Muyshondt a uno de sus colaboradores en mensajes de WhatsApp. “Uno nunca sabe. Miedo a morir no tengo. Pero si me joden… quien se va a estar cagando de la risa en su tumba soy yo”, escribió el 14 de febrero de 2020. Los mensajes eran una premonición: casi tres años después, el 9 de agosto de 2023, el fiscal general nombrado por Bukele ordenó arrestar a Muyshondt bajo cargos de revelación de secretos oficiales y otros. Seis meses después, el asesor de seguridad nacional murió en un hospital del Estado tras haber ingresado ahí con una lesión y una infección en el cerebro provocadas, según sospechan ahora personas cercanas a él y sugiere un mensaje que él envió mientras estuvo preso, por una golpiza.

La persona que recibió aquellos mensajes en WhatsApp en 2020 preguntó de quién sospechaba el asesor: ¿“Pero quiénes” querrían hacerle daño? Al responder, Muyshondt mencionó los nombres de funcionarios cercanos al presidente: “Rogelio, Peter, Osiris, Sanabria, etc”. Rogelio es Rogelio Rivas, entonces ministro de justicia y seguridad pública. Peter es Peter Dumas, amigo personal de Bukele y director vigente del Organismo de Inteligencia del Estado (OIE). Osiris es Osiris Luna Meza, exdiputado del partido Gran Alianza por la Unidad Nacional (GANA) nombrado jefe de la Dirección General de Centros Penales (DGCP) y viceministro de seguridad ad-honorem. Y Sanabria es Ernesto Sanabria, amigo íntimo del presidente, señalado, entre otras cosas, de violencia machista y de dirigir granjas de troles para acosar a periodistas y opositores.

Una de las tesis de Muyshondt, se desprende de decenas de mensajes que envió a colaboradores y personas cercanas, era que un grupo proveniente del partido GANA, comandado por el diputado Guillermo Gallegos y Luna Meza, se había apoderado del gabinete de seguridad de Bukele para enriquecerse. GANA fue la formación política con la que Nayib Bukele corrió por la presidencia en 2019 luego de que el Tribunal Supremo Electoral de El Salvador negara la inscripción de Nuevas Ideas, su partido.

Con el tiempo, varias investigaciones, sobre todo una de la Fiscalía General de la República de El Salvador (FGR) antes de que Bukele la controlara y otra de la Fuerza de Tarea Vulcano de los Estados Unidos, darían la razón a Muyshondt. Ambas oficinas colaboraron durante meses en una investigación sobre la corrupción en el gobierno Bukele, la cual tomaría forma hasta entrado 2020, durante el cierre por la pandemia de Covid-19. Antes de eso, Alejandro Muyshondt ya había alertado de la corrupción.

Aquellas investigaciones rindieron frutos. Algunas fueron fortalecidas por la Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en El Salvador (CICIES), un ente investigador supranacional financiado por la Organización de Estados Americanos (OEA) que Bukele en principio apoyó pero terminó clausurando cuando las investigaciones incluyeron a sus funcionarios. Basados en esas pesquisas, fiscales del Distrito Sur de Nueva York, apoyados por Vulcano, prepararon una acusación penal a Osiris Luna, la cual nunca se presentó a la corte pertinente por una decisión política, según confirmó un exfuncionario de la administración de Joe Biden en Washington.

Alejandro Muyshondt supo muy pronto de aquella corrupción.

Cuando el cierre por Covid-19 estaba por terminar, Muyshondt llevó la sospecha a Casa Presidencial, a la antesala misma del despacho de Nayib Bukele. En agosto de 2020, el asesor se reunió con Ernesto Castro, el secretario privado del presidente, a quien advirtió de que el narcotráfico y la corrupción a gran escala vivían en las entrañas del gobierno.

Ibrajim Bukele, hermano del presidente y uno de sus asesores más cercanos, también escuchó las quejas de Muyshondt en una reunión que ocurrió después de las elecciones legislativas de febrero de 2021. La exposición de funcionarios oficialistas presumiendo artículos de lujo en redes sociales, le soltó el asesor a Ibrajim, podía pasarles facturas. “Diputados y alcaldes con carros nuevos, si no se toma esto en cuenta se va a erosionar el proyecto”, le dijo Muyshondt, quien creía que de todo lo bueno y malo que pasara en el oficialismo se responsabilizará al presidente: “En Nuevas Ideas todo gira alrededor de tu hermano; la gente no va a individualizar los robos”.

Prensa Comunitaria tuvo acceso a 8 horas de grabaciones hechas por Muyshondt durante conversaciones que tuvo con Castro, con Ibrajim Bukele, hermano del presidente, con Xavier Zablah, presidente del partido Nuevas Ideas, con el ministro de seguridad Gustavo Villatoro y con Juan Pablo Durán, ex presidente del estatal Banco de Desarrollo Social de El Salvador. Durante seis meses, a través de comparaciones digitales entre las grabaciones e intervenciones públicas de los funcionarios y de corroboraciones hechas con al menos diez personas que los conocen y han convivido con ellos, Infobae corroboró la autenticidad de los audios.

Además de los audios, Prensa Comunitaria tiene en su poder cientos de páginas del expediente médico de Muyshondt elaborado en el Hospital Nacional Saldaña, donde el exasesor fue ingresado a finales de septiembre de 2023, fotografías del cadáver tomadas por funcionarios del Instituto de Medicina Legal de San Salvador en el Instituto de Medicina Legal y decenas de textos intercambiados por mensajería electrónica con personas cercanas a él. La autenticidad de los textos se corroboró en entrevistas con excolaboradores, parientes, funcionarios en El Salvador y Estados Unidos, y con especialistas. La mayoría habló desde el anonimato por temor a represalias del gobierno Bukele. Se buscó a los funcionarios y personas mencionadas en esta investigación, pero en la mayoría de los casos no hubo respuesta; cuando sí la hubo así se señala.

Lo que todos estos documentos y entrevistas cuentan es la historia de un hombre que llegó al gobierno de Bukele a hacer inteligencia política y trabajar en ciberseguridad, que se decepcionó muy pronto por lo que vio dentro del nuevo gobierno y se frustró por la inacción del presidente, un hombre a quien él admiraba. Y cuentan también la historia de cómo el Estado salvadoreño lo arrestó, le montó una investigación criminal y lo vio morir después de, presumiblemente, haberlo torturado.

“En Asocambio hay un gran desvergue (desorden), tigre”

Alejandro Muyshondt enciende la grabadora del teléfono celular antes de entrar a la oficina de Ernesto Castro, el secretario privado del presidente Nayib Bukele, en el edificio neoclásico que aloja a la casa presidencial de El Salvador en la zona suroeste de la capital. Lo graba todo, como suele hacerlo cada vez que se reúne con funcionarios poderosos del gobierno salvadoreño, sus colegas.

En esta reunión, que ocurre en agosto de 2020, Muyshondt y Castro hablan de amenazas a la ciberseguridad de la presidencia, de corrupción en el sistema carcelario y del malestar de la embajada de los Estados Unidos con Guillermo Gallegos, diputado y aliado de Bukele al que agentes federales en Washington siguen la pista por narcotráfico desde al menos 2014.

Alejandro Muyshondt tiene 43 años cuando va a este encuentro en casa presidencial. Han pasado poco más de 18 meses desde que, en parte como agradecimiento por todo lo que hizo por él en momentos difíciles, Nayib Bukele lo nombró asesor nacional de seguridad al inicio de su primer periodo presidencial en junio de 2019. El presidente y el asesor no son amigos íntimos pero si han compartido batallas y detalles, como la vez en que Muyshondt le regaló una pistola Sig Sauer P226 Legion. “Ya la tengo en mis manos. Gracias, ‘brother’, por el regalo. Te pasaste”, le agradeció Bukele el 17 de septiembre de 2019 por medio de un mensaje en WhatsApp que acompañó con una foto del arma.

No son tiempos buenos para Muyshondt cuando se encuentra con Castro. Desde que lo nombró asesor de seguridad nacional, Bukele no le presta demasiada atención y la mayoría de los requerimientos que ha hecho para su despacho -computadoras, más personal, viáticos para sus guardaespaldas-, en el que trabajan unas 20 personas, suelen quedarse archivadas, muchas de ellas en la oficina del secretario privado. Tras largos meses de encierro por la pandemia de Covid-19, el asesor se siente relegado. Pero la plática con Castro le deja algunas promesas: el secretario se compromete a crear una plaza más para su oficina, a resolverle algunos asuntos de dinero y a colaborar más de cerca con él.

Desde el principio, Muyshondt ha pedido al secretario privado permiso para hablar “con franqueza, sin temor a represalias y despidos”. Castro ha contestado con una risa. Con franqueza, el asesor de seguridad le informa al segundo de Bukele en Casa Presidencial sobre un escándalo de corrupción que está por reventar, el de ASOCAMBIO, una asociación creada para administrar dinero proveniente de tiendas carcelarias que es controlada por Osiris Luna Meza, el director de prisiones. Esta es parte de la plática, que solo ha sido editada para mayor claridad (el audio original está disponible):

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “En ASOCAMBIO hay un gran desvergue (desorden), tigre. Hueveyo de a galán (robo descontrolado). Quitaron a Jesús de la O, pero la dama (amante) sigue ahí. Y en la Fiscalía están armando un expediente de esa mierda. La mamá de Osiris (Luna) empezó a ensamblar ciertos grupos de proveedores: “vos me das los tamales y vos me das no se qué” y siempre hay una comisión (de dinero) de por medio. Esta persona, con Jesús de la O, estuvo en ese esquema; (los fiscales) tienen conversaciones, tienen un montón de cosas que la Fiscalía pudiera tomar en cuenta. Se empezaron a hacer de la nada un vergo de pisto (dinero)… Esa mierda (el periódico independiente) El Faro ya también tiene indicios de eso…”

- Ernesto Castro: “…Ya los tienen bien taloneados (ubicados)”

- Muyshondt: “Y eso es una bomba que puede ser bien contraproducente si la tiran antes de elecciones. Es un vergazo (golpe) que está bien documentado y es bien difícil desmentirlo y crear una cortina de humo para quitarse un vergazo de ese tipo…”

- Castro: “Sí.”

La “mamá de Osiris” es Alma Yanira Meza. Poco después de esta conversación, dos medios salvadoreños hacen públicos documentos que acreditan el desvío irregular y uso de USD 8.5 millones en el sistema carcelario. La FGR, en efecto, ha abierto un expediente que entonces no es público y ha puesto a Luna y a su madre como los principales sospechosos del desvío. Los fiscales, además, creen que madre e hijo son líderes de una red de corrupción que ha creado plazas fantasmas para apropiarse de salarios no entregados y de dar contratos por servicios en las cárceles a cambio de coimas. En pocos meses, gracias a esas plazas, la red de los Luna Meza se ha hecho con unos USD 300,000 según las investigaciones de la fiscalía.

Los expedientes fiscales también muestran que Jesús de la O, el hombre al que Muyshondt se refiere en su conversación con Castro, es el principal ejecutor de los cobros irregulares.

Para 2020, la Fiscalía también investiga a Luna por su rol en la negociación de un pacto de gobernabilidad con las pandillas MS13 y Barrio 18, que entonces está vigente. La Fuerza de Tarea Vulcano, creada por la administración de Donald Trump en Washington para apoyar la lucha anticorrupción en Centroamérica, colabora con las pesquisas en torno a Luna Meza. A finales de 2021, cuando ya Joe Biden es presidente en Estados Unidos, el Departamento de Estado y el del Tesoro sancionan a Meza y a su madre y los señalan de corrupción. En el San Salvador de Bukele nada pasa.

Cuando, en la reunión de agosto de 2020, Muyshondt cuenta al secretario privado sobre la red de corrupción en las cárceles, Castro anota el nombre de alguien, una de las supuestas involucradas en los crímenes, y pasa a otra cosa. Hasta la fecha, a pesar de que este termina siendo uno de los primeros grandes escándalos de corrupción que salpica al gobierno Bukele, el principal señalado sigue en su cargo. Cuando en mayo de 2021 los diputados de Nuevas Ideas, el partido oficialista, nombran a un fiscal general leal a Bukele, las investigaciones a Luna Meza y su madre quedan enterradas.

El silencio y la inacción hacen crecer la frustración de Muyshondt, la que había iniciado a finales de 2019, cuando ya hablaba de estas cosas a personas allegadas a él. “Están robando millones”, ha escrito el asesor de seguridad a uno de sus contactos el 14 de febrero de 2020. Un día después, en un diario electrónico en el que apunta los sucesos más relevantes de cada jornada -a parte del cual Prensa Comunitaria tuvo acceso-, Muyshondt escribe: “Ahora entiendo porque a pesar de que se me había ofrecido el OIE (Organismo de Inteligencia del Estado) no me lo terminaron dando. Obviamente necesitan a alguien que les cubra todas las chanchulleras (suciedad) que están haciendo en CAPRES (Casa Presidencial). Por esa misma razón me tienen aislado.”

La dinámica de las reuniones que Alejandro Muyshondt tiene con los funcionarios de Bukele, entre agosto de 2020 y marzo de 2021, es similar. El asesor de seguridad suele abrir con peticiones de apoyo a su oficina y al trabajo que él hace. Luego, se despliega hablando de lo que él ha hecho y ofrecido al gobierno en temas como la ciberseguridad y tecnología y se queja de la poca atención que él, su oficina y sus propuestas reciben. En medio de las pláticas, siempre, Muyshondt introduce su preocupación por lo que, a través de su trabajo de inteligencia, recoge sobre corrupción y su análisis sobre el daño que esto puede traerle al presidente. Nunca, en estas pláticas, los funcionarios desechan los señalamientos a personas como Osiris Luna o Guillermo Gallegos, pero tampoco dicen que harán algo al respecto.

“Están cuestionando la amistad de N con Gallegos”

Cuando habla con el secretario privado de Bukele en 2020, Alejandro Muyshondt toca un tema que será recurrente en otras conversaciones, el del diputado Guillermo Gallegos, un hombre al que Estados Unidos investiga desde 2014 por sospechas de nexos con el tráfico de drogas, según dos funcionarios del Departamento de Justicia en Washington confirmaron a Prensa Comunitaria.

Gallegos es, en 2020, un diputado que lleva 20 años en el Congreso, a donde llegó como representante del partido ARENA, de derecha. Con el tiempo, junto a otros operadores políticos desechados por el conservadurismo tradicional salvadoreño, fundó la Gran Alianza de la Unidad Nacional (GANA). En 2019, tras varios cambios de lealtades políticas, Gallegos y GANA le prestan el partido a Bukele para que corra por la presidencia luego de que este no alcanza a inscribir a tiempo a Nuevas Ideas. Desde entonces, Bukele y Gallegos son amigos, buenos amigos.

En la conversación de 2020 con Muyshondt, el secretario Ernesto Castro confirma los vínculos de amistad. “Aquel (Gallegos) es bien chero (amigo) de Herbert (Saca) y es bien chero de Nayib”, dice el funcionario. Herbert Saca, el otro aludido en la plática, es primo del expresidente Antonio Saca, quien guarda prisión por delitos de corrupción. Herbert ha sido señalado por alianzas con la banda de narcotraficante Los Perrones, una de las más importantes en la historia del crimen organizado salvadoreño, y de asistir a gobiernos anteriores -además de al de su primo al del expresidente Mauricio Funes- en la compra de diputados.

Sobre Gallegos pesan varios señalamientos públicos, incluso investigaciones de autoridades judiciales salvadoreñas. En 2018 un examen de la Sección de Probidad de la Corte Suprema de Justicia (CSJ), la oficina que investiga el crecimiento patrimonial de los funcionarios, determina que Gallegos ha usado de forma irregular unos USD 100,000 y que ha intercambiado dinero con Adolfo Tórrez, otro operador político que, al igual que Herbert Saca, ha tenido vínculos con la banda de narcotraficantes Los Perrones. Dos investigaciones del periódico El Faro revelan, además, que Gallegos cobra viáticos por viajes a España que nunca ha hecho y que ha desviado medio millón de dólares de la Asamblea Legislativa a una ONG de la que su esposa era directora. Cuando Nuevas Ideas, el partido de Bukele, logra mayoría en la Asamblea Legislativa, en febrero de 2021, sus diputados montan una comisión para investigar entrega de fondos legislativos a organizaciones civiles; a las financiadas por Gallegos no las tocan.

Pero el principal problema de Gallegos nunca ha estado en El Salvador, donde siempre salió bien parado de las investigaciones, sino en Estados Unidos. El Buró Federal de Investigaciones sigue la pista del exdiputado salvadoreño desde al menos 2014 por posibles nexos con el narcotráfico. Prensa Comunitaria habló con un agente especial del FBI y con un exdiplomático estadounidense que estuvo estacionado en El Salvador en aquellos años; ambos confirmaron las investigaciones.

Para 2016, tres años antes de que Bukele asuma como presidente, ya una corte en el Distrito Sur de Nueva York (SDNY) ha abierto una investigación formal a Gallegos. Aquel año, cuando aún no trabaja para Nayib, Alejandro Muyshondt viaja a la sede del SDNY en Manhattan para hablar, entre otras cosas, de Guillermo Gallegos, a quien él ya conocía bien: Muyshondt ha militado en GANA, el partido del exdiputado.

En 2020, le dice Muyshondt a Castro, una agente de la Agencia Central de Inteligencia (CIA) estacionada en San Salvador ha vuelto a hacer preguntas sobre Gallegos y, esta vez, sobre su relación con el recién estrenado presidente Bukele:

“Hay un caso que se está llevando en el SDNY a donde (Guillermo) Gallegos está muy metido y está este fiscal de la DEA que se llama Eric Stouch y tienen una obsesión con Gallegos se pudiera decir… A mí Gallegos me pela (no me importa) …, la cosa es que la que está encargada de la inteligencia aquí de los Estados Unidos está cuestionando el porqué de la amistad de N con Gallegos. Pregunta que por qué, si lo ha hecho socio o lo está encubriendo”, advierte Muyshondt al secretario privado. En un momento, Castro intenta minimizar la relación de Gallegos con Bukele, pero luego acepta que ambos hombres son amigos. Parte de la conversación:

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “Me preocupa”.

- Ernesto Castro: “Pero N no tiene gran amistad con Gallegos…”

- AM: “Es que no es lo que N transmite…”

- EC: “Digo, si tienen amistad, pero una amistad… ¿Cómo quién? Bueno, como con Herbert (Saca), cabrón, la misma, siento yo.”

- AM: “Yo solo te digo, hay que tener mucho cuidado con esa vaina.”

- EC: “Sí, sí… De hecho, te digo, para mí aquel (GG) es bien chero (amigo) de Herbert y es bien chero de Nayib.”

- AM: “Yo también soy chero de H.”

- EC: “Yo lo sé, yo igual… El punto es…”

- AM: “La onda es que eso le puede afectar bastante su imagen (a Bukele)” … “Gallegos entre más se jacta de la amistad que tiene con aquel (Bukele), más popularidad, más votos.”

- EC: “Ha sido vivo (astuto), ¿verdad?”

Los estadounidenses, le dice Muyshondt a Castro, perciben que Bukele protege a Gallegos. “Es preocupante la parte de los gringos, que ya están cuestionando que el hijueputa de Gallegos esté en sociedades con N o si N lo está protegiendo”, le comenta. La alarma del asesor de seguridad nacional tiene fundamento: por años, Washington ha sospechado que Gallegos tiene alianzas con el narcotráfico local y movimientos de grandes cantidades de dinero en bancos extranjeros. El secretario privado, de hecho, sabe algo de todo aquello.

Castro acepta que el Organismo de Inteligencia del Estado (OIE) les hizo llegar, a él y a Bukele, un informe en el que había información comprometedora para Gallegos. El secretario da a entender que no hicieron algo al respecto. “En campaña… a nosotros la OIE nos daba un reporte, pero palomísima (impresionante) en donde estaban movimientos de las cuentas en el exterior… Y todavía me acuerdo (de) que le digo yo… Mirá… y qué hacemos con esta mierda… Nada, ahí dejémoslo, que sigan buscando, nos vale verga (no nos importa)”, dice el secretario.

Muyshondt es bastante vocal sobre su preocupación respecto a Guillermo Gallegos. La misma advertencia que lleva a la oficina de Ernesto Castro la repite, palabras más palabras menos, en otras reuniones con funcionarios cercanos a Bukele. Se lo dice a Ibrajim Bukele, hermano del presidente y su principal asesor económico y comercial, y a Xavier Zablah, primo de Nayib y presidente del oficialista partido Nuevas Ideas. Ambos escuchan y optan por guardar silencio.

El día en que Alejandro Muyshondt es capturado en San Salvador, por una investigación que el fiscal de Bukele abre basado únicamente en dos notas publicadas en medios de noticias falsas dirigidos por un propagandista del gobierno, el presidente publica en sus redes sociales el detalle de las acusaciones contra su asesor de seguridad nacional. Uno de los delitos imputados, dice el mandatario antes de que la Fiscalía haga un anuncio formal, es revelación de secretos oficiales que, según Bukele, Muyshondt ha compartido con periodistas y “con un gobierno extranjero”.

Alejandro Muyshondt ha hablado, en efecto, con los estadounidenses. Es parte de su trabajo. El círculo más cercano del presidente lo sabe, entre otras cosas, porque el mismo Muyshondt se los ha dicho cuando les habla de las investigaciones al diputado Gallegos. El asesor se lo dice, entre otros, al secretario privado Castro, a Ibrajim Bukele, el hermano, y a Xavi Zablah, el primo del presidente y jefe del partido Nuevas Ideas. Esta es parte de una de las conversaciones con Zablah que Muyshondt ha grabado en su teléfono celular:

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “He estado trabajando con la DEA… con la encargada de inteligencia, me ha dicho: o su presidente está protegiendo a Gallegos o su presidente está con Gallegos…”

- Xavier Zablah: “Yo lo sé y lo sabemos…”

- AM: “Ojalá aquel vaya marcando su distancia, porque eso nos va a traer un costo político bien grande…”

- XZ: “Lo sé.”

- AM: “Mirá, los gringos le tienen a Gallegos un vergo de mierdas, tanto así que en el USDNY (fiscalía del distrito sur de Nueva York) tiene un expediente grande… Lo están haciend ‘jayanamente’ (descaradamente), están desembarcando en San Juan La Herradura…Cuando incautaron USD 1.2 millones en droga, quién fue el que saltó, Gallegos saltó y le habló al chele (Mauricio) Arriaza (Chicas, director de la Policía), amenazando con destituirlo…”

- XZ: “Mirá, yo de esos temas, cabrón…”

Un alto jefe policial que ha colaborado en el pasado con Mauricio Arriaza Chicas, el director de la Policía Nacional Civil nombrado por Nayib Bukele, confirma que, en al menos dos ocasiones, Gallegos llama a Arriaza y que, en una de ellas, se refiere a un decomiso de drogas. “Ya la cagan ustedes, ustedes no están decomisando, están haciendo tumbes porque la merca la estaba vendiendo Torero (un supuesto narco no identificado) y la sacaba por puntos ciegos a los chapines (guatemaltecos) que les pagaban a USD 6,000 el kilo”, habría dicho el diputado según este oficial.

Conversaciones y mensajes de texto compartidos con uno de sus colaboradores revelan que desde al menos mediados de 2020 el asesor de seguridad se entrevista con dos agentes del Departamento de Justicia asignados a la Fuerza de Tarea Vulcano, a veces fuera del país, en lugares como Ciudad de Panamá, Madrid, Ciudad de Guatemala, Miami, incluso en Francia. Dos oficiales que trabajan con el gobierno de Joe Biden en Washington confirman esta relación, así como un ex miembro del Ministerio Público salvadoreño que estuvo en contacto con Vulcano.

“Nuestros malos que sean nuestros malos”: El proyecto C815 para espiar a periodistas y opositores

Cuando en agosto de 2020 se reúne con Ernesto Castro, el secretario privado de Nayib Bukele encomienda una misión particular a Alejandro Muyshondt. Le pide montar una oficina de espionaje político, un centro de inteligencia le llama Castro.

La idea toma forma en dos reuniones. En la primera, donde también se ha hablado del diputado Gallegos, Castro explora la posibilidad de que el asesor de seguridad nacional monte, desde su oficina, una operación clandestina para obtener información de personas de interés. Le pide que, en el corto plazo, le entregue un proyecto. Así empieza aquella plática:

- Ernesto Castro: “¿Vos estás haciendo trabajo de inteligencia?”

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “Sí, aunque no se me asigne pero sí. De hecho es uno de los temas que quiero tocar con vos…”

Cuando la conversación ocurre, ya entrado el segundo año de Nayib Bukele al frente del Órgano Ejecutivo, el presidente gobierna sin correlación política en el Legislativo. Bukele no ha salido mal parado del coronavirus: el presidente ha sido uno de los primeros en cerrar su país, en marzo de 2020, también ha construido un hospital exclusivo para atender a afectados por la enfermedad, y ha emprendido una política de vacunación eficiente. Luego, el Banco Mundial dirá que Bukele ocultó la cifra real de fallecidos y los medios locales publicarán investigaciones cuestionando la efectividad del hospital para el coronavirus. Pero eso será luego. Ahora, los hombres de Bukele están por enfrentar la primera elección legislativa y quieren ganar mayoría en la Asamblea. El secretario privado del presidente quiere más información. Eso le pide a Alejandro Muyshondt. Así sigue la conversación:

- Ernesto Castro: “¿Y cómo hacemos para poner una inteligencia política?

- Alejandro Muyshondt: Se puede pero sin ponerla…

- EC: Mmmjm.

- AM: No lo podés hacer oficial, ¿verdad?

- EC: No.

- AM: Ahora, yo te digo, serían servicios clandestinos.

- EC: Paletas de chocolate y de vainilla… ¿Y qué alcance se tendría?

- AM: Depende de lo que querés hacer… Querés hackear correos, querés hackear Facebook… Eso es lo que se hace, y de ahí también se le puede dar seguimiento, con seguimiento ya es otra onda.

- EC: ¿Podrías hacer vos un proyectito chiquito? Cuando te digo chiquito es chiquito de un par de gentes, ¿verdad? Y si vemos que esta mierda nos está tirando información y vale la pena… ¿Para cuándo…?

- AM: La gente para ya… Hay ciertas cosas que mejor no tenerlas acá: se alquila un servidor en Holanda por decirlo así y desde ahí se hacen los ataques, o Ucrania. Nunca lo he hecho con servidores propios, siempre pagados para tener el poder de procesamiento allá en otro lado.

Lo siguiente es que Castro pide a Muyshondt una reunión pronto para revisar el proyecto y tomar decisión. Quedan para reunirse una semana después y así lo hacen. El asesor de seguridad nacional llega al segundo encuentro acompañado de Raúl Torres, ingeniero informático y su hombre de confianza. Los dos hombres entran al despacho de Ernesto Castro. Musyhondt, como lo hizo en la ocasión anterior, lleva la grabadora de su celular encendido.

Al entrar, Muyshondt presenta a Torres y ofrece un pequeño “background” de su asistente. Torres fue, dice el asesor, quien le ayudó a tumbar en 2019 el sitio de Revista Factum, el medio que en septiembre de aquel año reveló que Nayib Bukele había recibido USD 1.9 millones de Alba Petróleos al inicio de su carrera política, cuando era alcalde de Nuevo Cuscatlán. Alba Petróleos es la filial salvadoreña de Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), un conglomerado de empresas a través de las que, de acuerdo con fiscales estadounidenses y salvadoreños, se lavaron millones de dólares.

Muyshondt asegura que la intervención a Factum se hizo por una orden directa aunque en el audio no queda claro de quién. “Cuando Factum nos empezó a volar verga (atacar) tumbamos a Factum casi tres semanas… Bueno, la orden vino directamente de… para bajar Factum y lo hicimos con pocos recursos”. Los editores de este medio, según ellos mismos publicaron en 2020, confirmaron que estuvo fuera de línea una semana en octubre de 2019, después de la publicación del reportaje que vinculaba a Bukele con Alba Petróleos. Una investigación posterior del medio determinó que Raúl Torres había estado implicado en el ataque a la revista.

En la plática con Ernesto Castro, Muyshondt dice que hacer lo mismo con periódicos más grandes, como El Diario de Hoy o La Prensa Gráfica, es más difícil. El secretario privado aclara que eso no es lo que le interesa, sino escuchar a periodistas específicos. Aquí parte de la conversación:

- Ernesto Castro: “A nosotros nos vale verga (no nos importa) ‘hackear’ El Diario de Hoy.”

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “Pero se puede…”

- EC: “Nosotros lo que queremos es intervenir a (Jorge) Beltrán Luna, que es completamente diferente… Ehhh… Nosotros ni bajar El Faro… Todo eso son como picardías, ¿verdad? Jodamos a estos y los tenemos una semana, yo qué sé… Pero lo interesante es intervenir a… a Carlos Dada… a esos…”

- AM: “Pero eso está fácil.”

- EC: “Vaya, hagámoslo, pues…”

Antes, en la conversación, ha sido Raúl Torres el que ha perfilado de qué se encargará la oficina de espionaje político, a la que Muyshondt deja bautizada como proyecto C815. Ha explicado a Castro que el primer paso será intentar ingresar a los dispositivos electrónicos y cuentas de correo de los sujetos de interés a través de un método conocido como “phishing”, que consiste en enviar enlaces engañosos para que quien los abra dé acceso, sin quererlo, a su información.

Torres también ha expuesto los objetivos. La información que recolecten, ha dicho en la reunión, servirá para “armar campañas”, para “cortar” el contacto de los periodistas con sus fuentes y para “saber cuando se esté armando un reportaje”. El gran problema que tiene el gobierno, apunta Torres, es la “filtración” de documentos.

Antes de que Castro dé su visto bueno al proyecto, Alejandro Muyshondt ha pedido que la comunicación sobre el mismo sea compartimentada, y que se excluya de ella a otros entes de inteligencia en el Estado, como la OIE, de la que el asesor de seguridad no tiene un buen concepto. Aquí una parte de esa conversación:

- Alejandro Muyshondt: “¿Esto lo vamos a estar manejando vos y yo y el presidente o…?”

- Ernesto Castro: “Sí.”

- AM: “Porque no me sentiría cómodo trabajando con más personas.”

- EC: “Lo que pasa es que quiero entender exactamente qué es para tampoco entrar… en las funciones de los otros…”

- AM: ¿Y qué hacen los otros, vos?

- EC: “No creas… Hacen un par de cositas ahí…”

- AM: “Yo he visto reportes, tigre, dan risa… Vos dirás… Ahí es cuna de infiltrados que tenés ahí.

- EC: Eso sí creo yo también…

- AM: No son gentes leales al presidente, son gentes leales a su sueldo.

- AM: Entre menos gente se involucre en esto…

- EC: No, eso sí, esto no va a estar con nadie, absolutamente.

Antes de dar por terminada la plática, y de que Muyshondt y Castro hayan revisado algunos detalles sobre posibles contrataciones y necesidades administrativas del proyecto, el secretario privado vuelve al objetivo central de esta idea: darle a Nayib Bukele información de periodistas y opositores, recabada de forma ilegal, que pueda tener utilidad política para el presidente. De paso, Castro lanza su propia crítica al OIE, del cual dice que ha perdido el foco al embarcarse en recabar información sobre personas que, se supone, son aliados del gobierno y de casa presidencial.

“Vale verga… Nuestros malos que sean nuestros malos, ahí vemos después estos hijos de puta cómo salimos de ellos, pero los que nos quieren hacer mierda son los de afuera. Lo que tenemos que ver es lo que hace Neto Muyshondt (entonces alcalde de San Salvador por el partido ARENA, de oposición, primo de Alejandro y quien lleva más de tres años preso) … Lo que tenemos que ver es lo que haga un Norman Quijano (exalcalde de San Salvador por ARENA, acusado por supuestos pactos con las pandillas y prófugo), un Rodolfo Parker… Al hacer esto podemos tener muchos elementos para tener contento al hombre, son cosas que el hombre necesita”, cierra Ernesto Castro.

El pleito final y la captura

Después de aquellas conversaciones, la presencia de Alejandro Muyshondt en el ojo público es intermitente. En privado sigue enviando informes a su jefe, el presidente, de forma periódica. Uno de los últimos está fechado en febrero de 2023. Muyshondt lo titula “Retos 2023” y enumera, entre ellos, la corrupción: “Hay varios malos actores dentro del gobierno”. A juzgar por las comunicaciones que el asesor de seguridad nacional tiene con uno de sus colaboradores en aquellos días, es poco probable que el presidente Bukele lea los reportes; no contesta ninguno, al menos por escrito.

A pesar del silencio del presidente, Alejandro Muyshondt sigue siendo una persona con líneas de comunicación abierta a diputados de Nuevas Ideas y con algunos de los asesores más cercanos a Nayib Bukele, como Sofía Medina, la secretaria de comunicaciones, y Sara Hannah, venezolana que habla al oído del mandatario en temas variados como la política internacional, las finanzas del Estado o estrategias comunicacionales. Habla por mensajería de WhatsApp con Hannah, quien en noviembre de 2022, le pide que desista de hacer señalamientos públicos al Banco Agrícola de El Salvador a propósito de un problema en el sistema de banca electrónica del que Muyshondt se ha hecho eco en redes sociales.

Y habla con Sofía Medina de varias cosas, entre ellas los encontronazos públicos que Muyshondt tiene en redes sociales con funcionarios del gobierno y de la presidencia. En mayo de 2023, uno de los pleitos que comenta con Medina marca el inicio del trecho final en la vida de Alejandro Muyshondt.

El 9 de mayo de 2023, en sus redes sociales, Muyshondt acusa de corrupción a Ernesto Sanabria, el secretario de prensa de la presidencia. Publica que Sanabria, uno de los hombres más cercanos al presidente hasta entonces, se ha gastado USD 77,193 en prendas de vestir en 11 meses cuando su ingreso anual es de USD 72,000. Una conversación en WhatsApp con Sofía Medina, la secretaria de comunicaciones de Bukele, quien de acuerdo con dos funcionarios consultados es adversaria política de Sanabria, revela que ella sabía de las acusaciones a este último y que a Muyshondt le habían dado una orden para ventilar toda aquella información.