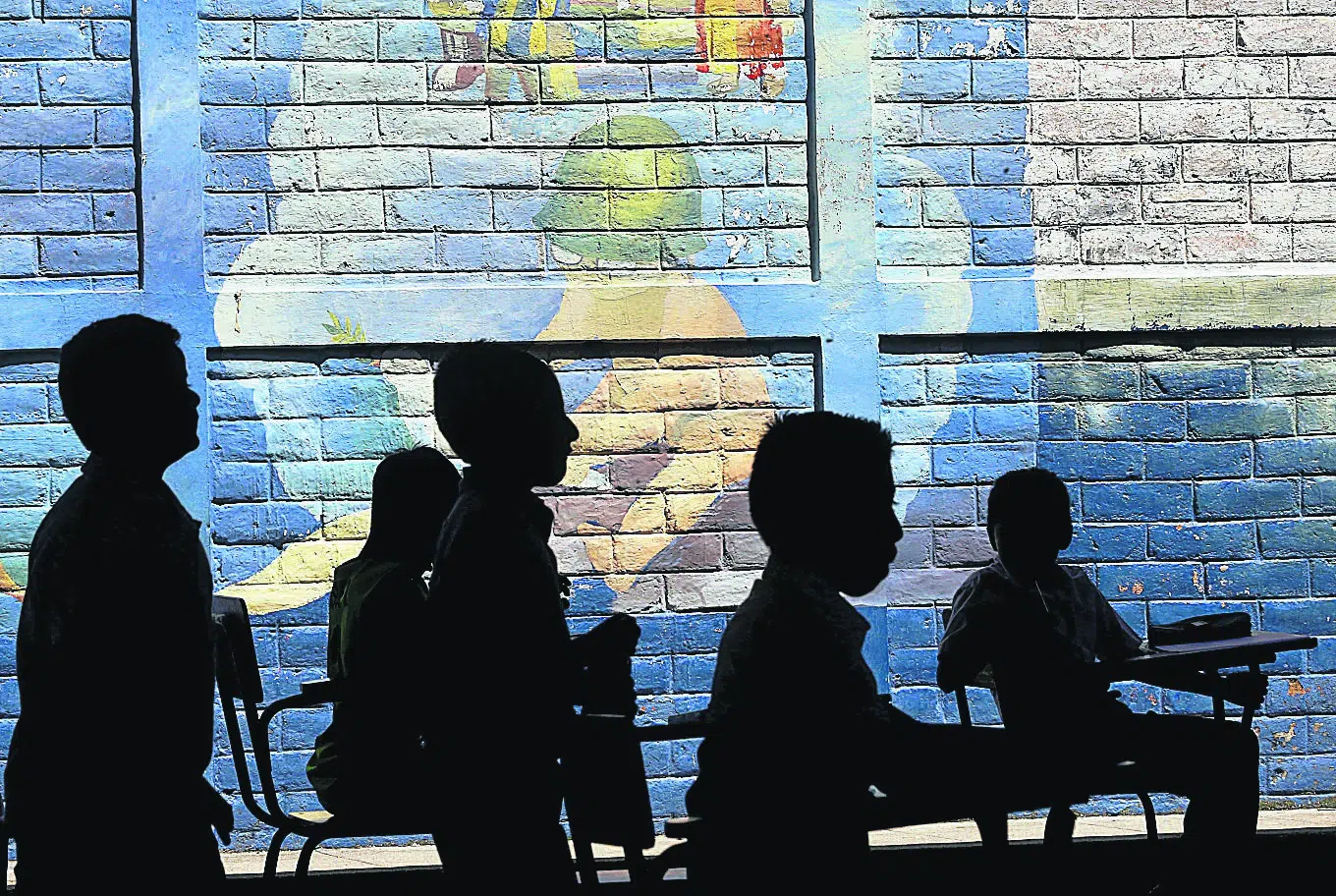

A recent report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) on violations of human rights in children and adolescents during the state of exception in El Salvador concludes that the security measure stigmatizes and criminalizes young populations. This assertion is supported by teachers and psychology specialists, who have documented cases of school dropout and anxiety and depression problems in students who have experienced detention or have family members or classmates in jail.

According to HRW, the majority of adolescent arrests during the state of exception have occurred in “low-income communities,” and those arrested have been subjected to “mistreatment and torture.” The international organization gathered cases of students who were taken out of their schools or were awaited after school hours to be arrested.

LA PRENSA GRÁFICA confirmed such cases with teachers from various schools in the country, who stated that many youngsters no longer attend classes because “they are afraid of being arrested,” and others are suffering from “anxiety and fear of the authorities due to fear of arrests.”

“The experience we have in the schools where many of our colleagues work is that there has been a dropout rate between 8 and 10% regarding the regime. Many students stop attending school due to being stigmatized, especially by the government’s threat to keep records of students considered problematic,” said Carlos Olano, general secretary of the Teachers’ Union for Education for All (SINDOPETS).

At the school where Daniel Rodríguez, secretary of the El Salvador Public Education Teachers’ Union (SIMEDUCO), works, an average of 20 to 30 students have dropped out since 2022. Among the reasons, he said, are the arrests of their parents.

“Then it happens that whoever took responsibility for them moved them to another place (displacement). Other parents have enrolled their children near their workplaces, and other young people have had to work,” he explained.

Regarding the stigmatization and criminalization of young people, Rodriguez stated that most of those arrested come from “communities where the gang or mara phenomenon took over the territories more, such as the neighborhoods of Soyapango, Ilopango, Cuscatancingo, Mejicanos, as well as cantons and hamlets. Also, young people from communities such as Bajo Lempa, where young people have been arrested for political reprisals.”

He also mentioned cases in neighborhoods like Altavista and the districts of Ilopango, Tonacatepeque, and San Martín, where “their populations have been stigmatized simply for living in those communities where the problem of criminal groups hit hard.”

Another teacher who preferred to remain anonymous for security reasons said that at his school, in the Western part of the country, there are only 173 students, and due to low enrollment this year, they had to remove the third cycle and keep only kindergarten to sixth grade.

“Before, we had just over 250 students in the school, but due to the dropout rate for the past two years, we had to close the third cycle. Many parents did not enroll their children; one of the reasons is that they had to leave the community or because the parents or even some minors were arrested by the regime,” he mentioned.

Regarding the abuse of authority by police and military officers, Rodríguez says that such treatment causes “irreversible psychological damage, which marks these young people for life. They have a great panic towards the security forces.”

Psychological effects

Pamela Rodríguez, a psychologist at the Legal Humanitarian Aid (SJH), has treated cases of arrested students and cases of children and adolescents who have relatives in prison due to the regime. After listening to these victims, she maintains that it is evident that after the traumatic event, they begin to develop “generalized anxiety” and, in very severe cases, “they start to approach dangerous behaviors or addictions to try to maintain control over what is happening.”

In many cases, Rodríguez has documented that students no longer want to go to school. In others, parents no longer let them go for fear of them being arrested. These students are around 17 years old and attend the third cycle or high school.

“For the moment, we have coined the syndrome of children and adolescents of the regime. They should be provided with psychological support from the moment they witnessed an arrest or were victims of one, but it is very difficult to obtain it because young people cannot afford a consultation, and when they seek this type of care in clinics, they are revictimized, which is why they do not return,” she said.

According to the specialist, the symptoms suffered by these victims worsen over time, and even if the relative is released, there are consequences: “they have this perception that the world is a dangerous place at this moment and think what could happen to me. And even if their relative is released, that thought will continue, and it will also determine many decisions they make in their lives.”

No official data

According to information collected by LPG Datos from the website of the Ministry of Education (Mined), between 2008 and 2021 (the last year that the causes of school dropout were published), there were 1.2 million students who stopped attending their schools for various reasons. Among the most notable are the change of the student’s residence, delinquency, parents not wanting their children to attend school, economic difficulties, or the students starting to work.

LA PRENSA GRÁFICA sent an email to the Minister of Education, José Mauricio Pineda, inquiring why they no longer publish data on school dropout, but as of the closing of this story, there was no response. The Ministry of Security’s communications department was also asked about the arrest of students, but there was no response either.

Régimen provoca deserción escolar y ansiedad en niños, niñas y adolescentes

Un reciente informe de Human Rights Watch (HRW) sobre violaciones de derechos humanos en niños, niñas y adolescentes durante el régimen de excepción en El Salvador concluye que la medida de seguridad estigmatiza y criminaliza a las poblaciones jóvenes. La afirmación es secundada por docentes y especialistas en psicología, quienes han documentado casos de deserción escolar y problemas de ansiedad y depresión en estudiantes que han experimentado una captura o tienen a familiares o compañeros de estudios en la cárcel.

Según HRW, la mayoría de capturas de adolescentes durante el régimen de excepción han sucedido en “comunidades de bajos ingresos” y estos, cuando son capturados, son sometidos a “malos tratos y torturas”. La organización internacional recopiló casos de estudiantes que fueron sacados de sus escuelas o eran esperados luego de estudiar para ser capturados.

LA PRENSA GRÁFICA confirmó este tipo de casos con profesores de varias escuelas del país, quienes afirmaron que muchos jóvenes ya no asisten a clases porque “tienen miedo de ser capturados” y otros están padeciendo “ansiedad y miedo a las autoridades por temor a capturas”.

“La experiencia que nosotros tenemos en los centros escolares donde trabajan muchos de nuestros compañeros es que ha habido una deserción entre un 8 y 10% con respecto al tema del régimen hay mucho estudiante que por haber sido estigmatizado deja la asistencia a los centros escolares, más por la amenaza que hizo el Gobierno de que se fichar a los alumnos que se consideraban problemáticos”, aseguró Carlos Olano, secretario general del Sindicato de Docentes de Una Educación para Todos (SINDOPETS).

En el centro escolar donde trabaja Daniel Rodríguez, secretario del Sindicato de Maestras y Maestros de la Educación Pública de El Salvador (SIMEDUCO), se han retirado un promedio de 20 a 30 estudiantes desde 2022. Entre las razones, según él, están la captura de sus padres.

“Luego pasa que quien se responsabilizó de ellos se los llevó a otro lugar (desplazamiento). Otros padres han puesto a estudiar a sus hijos cerca de sus lugares de trabajo y otros jóvenes han tenido que trabajar”, expuso.

Sobre la estigmatización y criminalización hacia los jóvenes, Rodríguez afirmó que la mayoría de los que han sido capturados provienen de “comunidades donde el fenómeno de la mara o pandilla se apropió más de los territorios, como las colonias de Soyapango, Ilopango, Cuscatancingo, Mejicanos, así como cantones y caseríos. También jóvenes de comunidades como el Bajo Lempa, dónde han capturado jóvenes por represalias políticas”.

También mencionó casos en colonias como Altavista y los distritos de Ilopango, Tonacatepeque y San Martín, donde “sus poblaciones han sido estigmatizadas por el simple hecho de vivir en esas comunidades donde golpeó duro el problema de los grupos criminales”.

Otro profesor que prefirió mantenerse en el anonimato por seguridad, dijo que en la escuela donde trabaja, en el Occidente del país,solo hay 173 estudiantes y que por la baja matrícula este año, tuvieron que quitar tercer ciclo y solo quedó de parvularia a sexto grado.

“Antes teníamos poco más de 250 alumnos en la escuela, pero debido a la deserción escolar desde hace dos años se tuvo que cerrar el tercer ciclo. Muchos padres de familia no matricularon a sus hijos, una de las razones es que tuvieron que salir de la comunidad o porque los padres o incluso algunos menores fueron capturados por el régimen”, mencionó.

Sobre el abuso de autoridad que han realizado policías y militares, Rodríguez asegura que este tipo de tratos causa “daños psicológicos irreversibles, que marca de por vida a estos jóvenes. Le tienen un gran pánico a los cuerpos de seguridad”.

Efectos psicológicos

Pamela Rodríguez, psicóloga del Socorro Jurídico Humanitario (SJH), ha tratado casos de estudiantes capturados y casos de niños y adolescentes que tienen a familiares en la cárcel por el régimen. Tras escuchar a esas víctimas sostiene que es evidente que luego del suceso traumático comiencen a desarrollar “ansiedad generalizada” y, en casos muy graves “comienzan a acercarse a conductas peligrosas o adicciones por intentar mantener un control sobre lo que está sucediendo”.

En muchos casos Rodríguez ha documentado que los estudiantes ya no quieren ir a la escuela. En otros los padres ya no los dejan ir por temor a que los capturen. Estos estudiantes ya rondan los 17 años y van a tercer ciclo o bachillerato.

“Por el momento le hemos puesto el síndrome de los niños y adolescentes del régimen. A ellos debería dárseles un acompañamiento psicológico desde que vieron una detención o fueron víctimas de una, pero es muy difícil obtenerlo porque los jóvenes no tienen cómo pagar una consulta y cuando buscan este tipo de atención en las clínicas reciben revictimización, por eso ya no vuelven”, opinó.

Según la especialista, los síntomas que padecen estas víctimas se agravan con el tiempo y aunque el familiar es liberado, quedan consecuencias: “tienen esa percepción que ahora el mundo es un lugar peligroso en este momento y piensan en qué me puede pasar. Y aunque sea liberado su familiar, ese pensamiento va a continuar y eso va a determinar también muchas decisiones que tomen en su vida”.

Sin datos oficiales

Según información recopilada por LPG Datos de la página web del Ministerio de Educación (Mined), entre 2008 y 2021 (último año que se publicó las causas de la deserción escolar) hubo 1,2 millones de estudiantes que dejaron de asistir a sus escuelas por diversas razones. Entre las que más destacan están el cambio del domicilio del estudiante, delincuencia, los padres no quieren que asistan a la escuela, hay dificultades económicas o que los estudiantes comenzaron a trabajar.

LA PRENSA GRÁFICA envió un correo al ministro de Educación, José Mauricio Pineda, consultando por qué ya no publican los datos sobre deserción escolar, pero la cierre de esta nota no hubo respuesta. También se consultó con el área de comunicaciones del Ministerio de Seguridad sobre la captura de estudiantes, pero tampoco hubo respuesta.