Saúl, a 16-year-old minor, was sentenced to 12 years in prison after the San Francisco Gotera Juvenile Court found him guilty of terrorist organizations based solely on the evidence presented by the Attorney General’s Office (FGR) against him: the testimony of the police officers who captured him.

The police officers’ testimony in court summarized this story: at 3 p.m. on April 19, 2022, when four officers were conducting preventive patrols in a municipality of Morazán, they received a call from a sergeant who told them that there were two gang members in the area. Upon finding them, the officers searched them but found nothing illegal. In that call, the sergeant stated that they should arrest them because they had information from the public that the minor collaborated in the collection of extortion money.

A month later, in Santa Ana, four police officers told a similar story to justify the arrest of Óscar, another 16-year-old minor. This story recounted that an anonymous person informed them that on a street in the neighborhood, several young people had gathered who seemed to be gang members. When the police arrived, everyone fled, leaving only Óscar and his sister behind. Both were arrested because, according to the police, he had been previously identified as a collector of “rent” in local stores.

These two accounts appear in two of the four judicial files of minors convicted under the state of exception, which LA PRENSA GRÁFICA accessed. The testimonies of the arresting police state that they were captured for gathering or because someone, anonymously and without making a formal complaint, accused them of being gang members.

In addition to police testimony, the documents follow the same pattern in the version of how the arrests occurred; the cases are based on reference evidence, and no illegal items were confiscated at the time of detention. There was also no material, documentary, or expert evidence that any of these minors had a criminal record.

Despite these procedural conditions and characteristics, judges have convicted minors, even to sentences of 12 years in prison, with elements that, in other analyzed sentences, have been labeled “subjective and personal imputations” that are not reliable to prove involvement with a gang by a judge and a Minor Chamber.

For two years, the government has promoted the state of exception as a strategy to end the gang problem in El Salvador, which has been heavily criticized for violating human rights and also affecting minors.

The Ministry of Justice and Security reported that from the time the measure was implemented on March 27th, 2022, to February 2024, 1,194 boys and girls had been captured and prosecuted. However, the 2024 Trafficking in Persons report, produced by the United States Department of State, shows the most current figure of children detained during the state of exception: 3,329 boys, girls, and adolescents imprisoned between March 2022 and December 2023. This data comes from an official report given by the National Council for Early Childhood, Childhood, and Adolescence (CONAPINA) to the United States Department of State.

In March 2022, the Legislative Assembly amended the Juvenile Penal Law so that when crimes were committed by gang members, the maximum sentence could be up to 20 years in prison for minors aged 16 and over, and up to 10 years for those who were 12 years old.

Despite the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which El Salvador is a party to, urging states to ensure that the minimum age of criminal responsibility is not less than 14 years and encouraging them to progressively increase the age of criminal responsibility.

This media outlet contacted the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, Attorney General’s Office, Supreme Court of Justice, and the National Council for Early Childhood, Childhood, and Adolescence on the subject, but none of the institutions provided a response.

Unjustified convictions

The day the police captured Saúl, who was accused of collecting rent at the time, they found nothing that could corroborate this version. There was also no record of the alleged complaints by neighbors.

The first officer to testify at the trial said that the police had an investigation that had been initiated three months earlier, but they did not capture him earlier because they did not have an arrest warrant against him. “(We did not capture him earlier) because we did not have an order for deprivation of liberty. The state of exception, according to decree 333, gave us the power to proceed with what is deprivation, so we proceeded,” she emphasized.

The social aspect included in the case against Saúl states that he is the second of five siblings, always stayed at home, and that the entire family worked in agriculture for their subsistence.

“He works in agriculture with his dad in his spare time since his priority is studying. He attends the Assemblies of God Church and plays soccer. His life goal is to continue his studies and work with his father to help with the local economy,” the text describes.

Although this description was included in the court case, the Attorney General’s Office insisted that Saúl collaborated as a “lookout” (surveillance) for the Ordon City Locos Salvatruchos clique. For this, they had a police expert testify in court who argued that his report was based on review records, profiles of the adolescents, and inputs that the police institution possessed.

Without any evidence to corroborate that Saúl indeed had that level of participation in the gang, the judge argued that there was “full certainty that he not only belongs to the structure, but also has been at the disposal of the orders given by the leaders of each clique and program for a while.”

In addition, the statements of the officers and the expert were sufficient to find him guilty. “They were able to detail how the structure was formed, as well as link the adolescents to the crime of illegal associations, detailing their functions within the gang (…).” The judge insisted that there was enough incriminating evidence against Saúl to hold him accountable.

Óscar was arrested a month after Saúl, only in the western part of the country, but with a similar version. It was 6:30 p.m. on May 21, 2022, Óscar’s sister, Blanca, who is older than him and accompanied by her son, had come to visit. She went to the store, located about 100 meters from the house, to buy candy for her son. As she made her purchase, the police appeared and said she had to accompany them. They put her in the patrol car and transferred her to the place where she lived with her mother-in-law and husband, a few blocks from where the arrest occurred.

The patrol parked right in front of Blanca’s house. She had not finished getting out when Óscar reached them on a motorcycle and the police asked who he was, to which he replied that he was her brother. “Get on, you’re coming with us too,” said the policeman, arresting him.

This story is as told in the testimonies of Óscar’s father, Blanca’s mother-in-law, and a neighbor who also witnessed the events.

In court, the Attorney General’s Office accused Óscar of belonging to the Hoover Locos Sureños HVLS clique of the 18th Street gang, with the rank of extortioner and as a collaborator. Two of the four police officers who arrested him testified against him. The version both gave in the trial was that they were conducting preventive patrols in the area around 10 p.m. on May 21, 2022, when an unidentified person told them that there was a group of gang members gathered in the neighborhood who did not belong to the area.

Following the warning, they proceeded to intervene, but everyone fled except for Óscar and Blanca. The first officer to testify said that he had known Óscar for five months and had seen him asking people for money, “posting,” or riding a bike with other gang members.

“Some ran one way, others another way, but the only one they caught was the youngster who stayed in the area. There was no one else, the youngster walked in the direction of the others, not running, so they managed to catch up with him,” he added.

Óscar’s father has a different version: “The way the police claim they captured him is a lie because they said they arrested him in another place, at another time of night and that he was gathered with others, but that has nothing to do with what actually happened.”

With no other evidence to corroborate the officers’ statements, the Ahuachapán Juvenile Court determined that the witness accounts were “consistent” with the expert and documentary evidence.

“(The police) were emphatic in stating two important circumstances. One is that they received information from a person who did not want to be identified out of fear, and the statement of the police expert, who references that the area where the defendant resides and where he was captured has the presence of the 18th Street gang (…) The testimony of the witnesses that were presented is credible, as they were categorical, natural, and objective in providing information about the case,” the judge argued for the conviction of two years and six months.

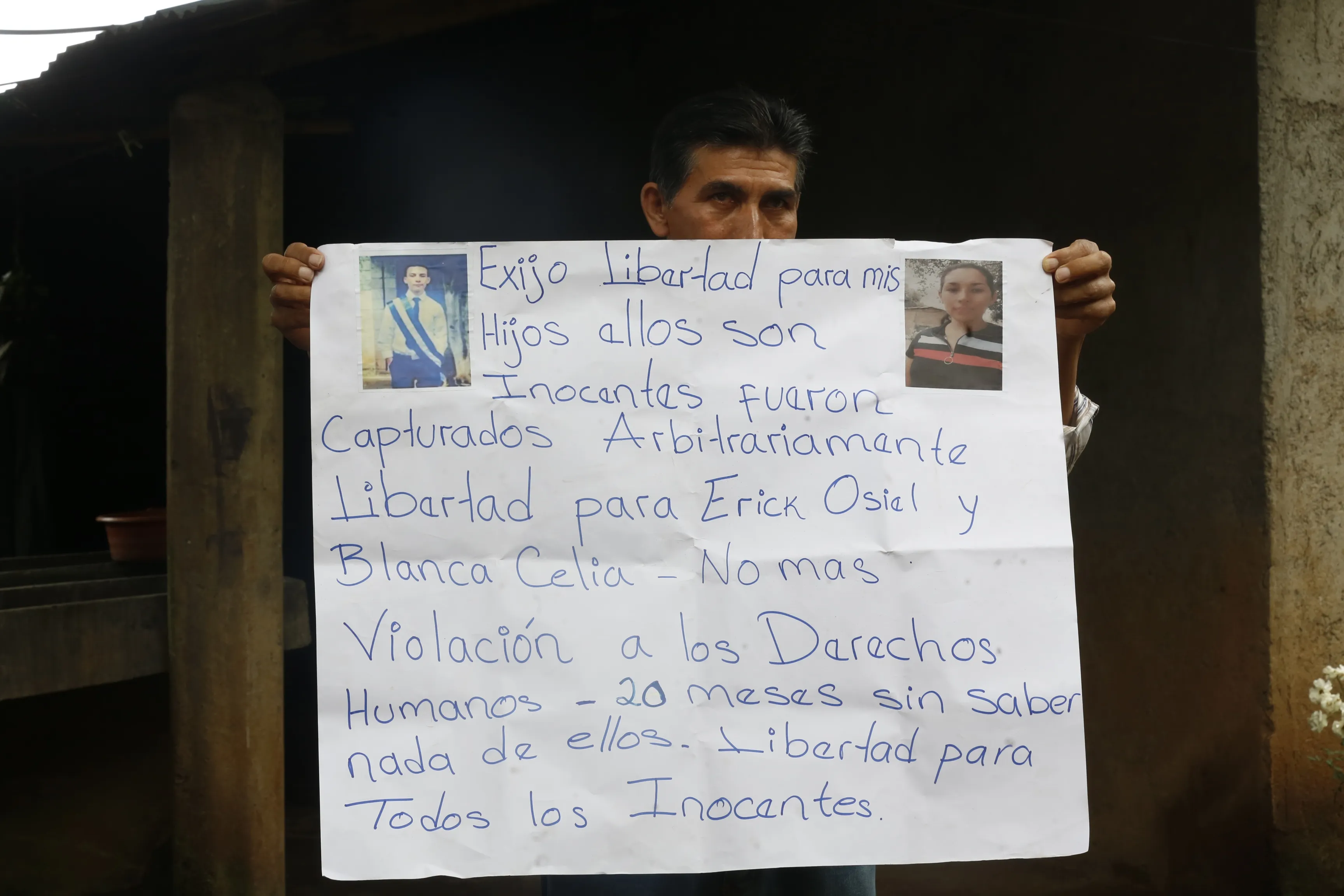

It’s the morning of June 28th, and sitting on the porch of the house, his father holds a sign with both hands, which he carries with him on marches to demand the freedom of his unjustly convicted son. It reads, “No more violation of human rights, 20 months without knowing about my son.” Since he was captured, the family has heard nothing from Óscar, and at the last hearing, the lawyer could not see him either.

“It’s as if he disappeared. It’s very hard times because everything happened so unjustly. I have always followed him to all the places where he was transferred since his capture. I used to work as a security guard and quit my job because of all the errands that had to be done, and it took me all day to go from Santa Ana to Ilobasco,” he emphasizes.

A conviction overturned by a Chamber

It was 6 p.m. on April 14, 2022, when a group of minors had decided to go out and play in one of the neighborhoods in the department of La Unión. The game had started when they were arrested by the police.

“They started searching us, taking off our shirts, socks, and caps, ripping them. They practically left us in our underwear. They searched us to see if we had drugs, but we didn’t. They wanted to plant them on us,” recalls Kevin, one of the six minors arrested that afternoon who ended up being released after 14 days.

That day, Esmeralda, a 14-year-old girl who was Kevin’s friend and his other friends’, had also arrived. He remembers how the police began telling her that she was “everybody’s woman.” According to the statement of facts in the court file, the officers also asked her how long she had been in a romantic relationship with one of the minors and when they last had sexual intercourse and at what time.

“She just had her boyfriend who was there with us, and that’s why they arrested her,” Kevin recounts.

Although a juvenile court convicted Kevin, a chamber found that the evidence was weak and full of contradictions.

Furthermore, the testimonial evidence presented by the Attorney General’s Office “violates the principle of sufficient reason, contradiction, and derivation to support the adolescent’s involvement as a collaborator in an illicit association.”

The situation was the same as in the other cases recounted by relatives of other minors: patrolling officers saw a group of people and decided to flee upon seeing them. They caught six of them and accused them of being gang members.

The Chamber emphasized that there was no evidence to support the police testimonies. “What must be sought is evidence that corroborates the testimony of a witness so that his or her statement does not remain a simple verbal statement considered subjective,” they warned.

A sergeant also argued that he had been following the case for months because the teenager was a collaborator of the local gang, and he knew about it from people in the area.

“As there is no other evidence establishing the adolescent’s collaboration with this type of structure, the reasoning and motivation given by the judge who declared the adolescent responsible is not in accordance with the law,” the court ruled.

It’s midday on Thursday, May 30, 2024, and a woman about 55 years old walks near the street where the six minors were captured. She says she knows Kevin and that he is a good student.

Her eyes redden and fill with tears as she remembers him: “He was a good boy, he worked very hard to study. I don’t know why they took him. His mother used to wash for others to send him to school, that’s how she did it until the ninth grade,” she whispers, her voice breaking and cracking into tears.

A kilometer away is Kevin’s house, where he now lives with his sister and grandfather as his mother was murdered after he was released. Resigned, he says he had to quit school after she died to help his grandfather with expenses.

After the arrest, when Kevin tried to return to school, he could not save the year; he had too many absences.

“I was in ninth grade, attending school in the afternoons, but while I was in jail, I lost the school year. The next year, I returned, but my peers teased me about whether I was a bad person and involved in wrongdoing,” he laments.

His days in jail were also not easy. He received food twice a day and was only allowed to drink water once or twice. What he misses most is being separated from his family. “All that time I was there, I couldn’t see my family. At night I felt depressed, sometimes I didn’t eat because of how much I missed them, and I would cry. The day I finally returned home, I cried, but out of joy,” he recounts.

Across the street where they were playing lived two of the captured minors, one of whom was released, Luis, 16, and the other convicted, Alberto, 15. His mother, Carmen, says Alberto has been detained for a year and a half at the Sendero de Libertad Social Integration Center in Ilobasco.

The La Union Juvenile Court sentenced him to two years in prison after finding him guilty of illegal associations, following the Attorney General’s Office accusing him of taking on the role of a “lookout” in the gang.

The officers’ testimonies at trial were contradictory. The first one relates that they received information through citizen complaints that gang members gathered in the neighborhood, and upon conducting preventive patrols, they located the minors and arrested them because they were not wearing uniforms that identified them as a soccer team while they were preparing to play on the street that April 14 afternoon.

The other version stated that they found the “subjects” and arrested them, “with no more to comply with what was established in the law of finding two or more people grouped.”

Pruebas para condenar a menores por el régimen: testimonios anónimos y de policías

Saúl, un menor de 16 años, fue condenado a 12 años de cárcel luego que el Juzgado de Menores de San Francisco Gotera lo declarara culpable del delito de organizaciones terroristas bajo la única prueba que la Fiscalía General de la República (FGR) ofertó en su contra: el testimonio de los policías que lo capturaron.

La declaración en juicio de los policías resumía esta historia: a las 3 de la tarde del 19 de abril de 2022, cuando cuatro agentes realizaban patrullaje preventivo en un municipio de Morazán recibieron la llamada de un sargento que les dijo que en ese lugar se encontraban dos pandilleros. Al encontrarlos los revisaron, pero no les encontraron nada ilícito. En esa llamada, el sargento manifestó que debían capturarlos porque tenían información de la ciudadanía que el menor colaboraba en el cobro de la extorsión.

Un mes después, en Santa Ana, cuatro policías contaron una historia similar para justificar la detención de Óscar, un menor también de 16 años. Esta narraba que una persona, que denunció bajo el anonimato, les informó que en una calle de la colonia se encontraban varios jóvenes reunidos que, al parecer, eran pandilleros. Cuando la Policía llegó al lugar, todos huyeron y solo quedó Óscar y su hermana. Ambos fueron detenidos porque, según los policías, él había sido identificado anteriormente como recolector de la renta en tiendas del lugar.

Estas dos versiones constan en dos de cuatro expedientes judiciales de menores de edad condenados en el régimen de excepción a los que tuvo acceso LA PRENSA GRÁFICA. Los testimonios de los policías captores cuentan que se los capturó por encontrarlos reunidos o porque alguien, de forma anónima y sin realizar una denuncia formal, los acusó de ser pandilleros.

Además del testimonio de policías, los documentos siguen un mismo patrón en la versión de cómo sucedió la detención, los procesos son basados en pruebas de referencia, no hubo decomiso de nada ilícito al momento de la detención y tampoco evidencia material, documental o pericial que alguno de estos menores tuviera antecedentes penales.

Pese a estas condiciones y características procesales, jueces y juezas han condenado a menores de edad, incluso a penas de 12 años de cárcel, con elementos que, en otras de las sentencias analizadas, han sido tildados como “imputaciones de carácter subjetivo y personal” que no son fiables para acreditar una vinculación a una pandilla por una jueza y una Cámara de Menores.

Desde hace dos años el Gobierno promueve el régimen como la estrategia para acabar con el problema de las pandillas en El Salvador, el mismo que ha sido duramente criticado por violar derechos humanos y que también ha afectado a menores de edad.

El Ministerio de Justicia y Seguridad publicó que, desde que la medida fue implementada el 27 de marzo de 2022 hasta febrero de 2024, habían sido capturados y procesados 1,194 niños y niñas. Sin embargo, el informe de Trata de Personas de 2024, elaborado por el Departamento de Estado de los Estados Unidos, arroja la cifra más actual de niños detenidos durante el régimen de excepción: 3,329 niños, niñas y adolescentes encarcelados entre marzo de 2022 y diciembre de 2023. Este dato se desprende de un informe oficial que el Consejo Nacional de la Primera Infancia, Niñez y Adolescencia (CONAPINA) le suministró al Departamento de Estado de los Estados Unidos.

En marzo del 2022, la Asamblea Legislativa hizo una reforma a la Ley Penal Juvenil para que cuando los delitos hayan sido cometidos por pandilleros, el máximo podrá ser de hasta 20 años de prisión a menores con 16 años cumplidos, y hasta 10 años cuando un menor haya cumplido los 12 años.

Esto pese a que en la Convención de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos del Niño, de la cual El Salvador es Estado parte, se insta a los Estados a que garanticen que la edad mínima de responsabilidad penal no sea inferior a 14 años, y los ha alentado a que aumenten progresivamente la edad de responsabilidad penal.

Este medio consultó al Ministerio de Justicia y Seguridad Pública, Fiscalía General de la República, Corte Suprema de Justicia y al Consejo Nacional de Primera Infancia, Niñez y Adolescencia sobre el tema pero ninguna de las instituciones brindó respuesta.

Condenas injustificadas

El día que la Policía capturó a Saúl, acusado de andar recolectando la renta en ese momento, no le encontró nada que pudiera comprobar esa versión. Tampoco había ningún acta registrada sobre las supuestas denuncias de los vecinos.

La primera agente que declaró en el juicio relató que la Policía tenía una investigación que había sido iniciada hacía tres meses, pero que no lo capturaron antes porque no tenían un acta de captura en su contra. “(No lo capturamos antes) debido a que nosotros no teníamos una orden de privación de libertad. El régimen de excepción, según decreto 333, nos dio la potestad de proceder a lo que es la privación, por eso procedimos”, recalcó.

El aspecto social incluido en el proceso contra Saúl cuenta que es el segundo de cinco hermanos, que siempre permaneció en el hogar y que todo el núcleo familiar trabaja en la agricultura para su subsistencia.

“Trabaja en su tiempo libre con el papá en la agricultura, ya que su prioridad es el estudio. Asiste a la iglesia Asambleas de Dios, juega fútbol, su proyecto de vida es poder continuar con sus estudios y trabajar con su padre para poder ayudar con la economía del lugar”, describe el texto.

Pese a que esta descripción incluida en el proceso judicial, la Fiscalía insistió en que Saúl colabora como “paro” (vigilancia) de la clica Ordon City Locos Salvatruchos, para ello llevó a declarar a un perito de la Policía quien sostuvo en el juicio que su informe se basaba en actas de revisión, perfiles de los adolescentes, además de insumos que la institución policial poseía.

Sin ninguna prueba que corroborara que Saúl efectivamente tenía ese rango de participación en la pandilla, la jueza sostuvo que existía “la plena certeza que no solo pertenece a la estructura, sino que tiene tiempo de estar a disposición de las órdenes dadas por los jefes de cada clica y programa”.

Además, que las declaraciones de los agentes y del perito eran suficientes para declararlo culpable. “Tuvieron la capacidad de detallar cómo estaba formada la estructura, así como vincular a los adolescentes en el delito de agrupaciones ilícitas, detallando sus funciones dentro de la pandilla (…)”. La juzgadora sostuvo que contaba con la suficiente prueba incriminatoria en contra de Saúl para declararlo responsable.

Óscar fue capturado un mes después que Saúl, solo que en el occidente del país, pero con una versión similar. Eran las 6:30 de la tarde del 21 de mayo de 2022, la hermana de Óscar, Blanca, que es mayor que él y andaba acompañada de su hijo, había llegado a visitarlos. Salió a la tienda, ubicada a unos cien metros de la casa, para comprarle dulces a su hijo, los pidió y fue entonces cuando la Policía apareció y dijo que debía acompañarlos. La subieron a la patrulla y la trasladaron al lugar donde ella vivía con su suegra y esposo, a unas cuadras de donde ocurrió la detención.

La patrulla se estacionó justo enfrente de la casa de Blanca. No había terminado de bajarse ella cuando Óscar los alcanzó en una moto y los policías le preguntaron quién era él, a lo que respondió que era el hermano. “Subite, vos también te vas con nosotros”, dijo el policía y lo arrestó.

Así lo cuentan los testimonios del papá de Óscar, la suegra de Blanca y una vecina que también presenció los hechos.

En los tribunales, la Fiscalía acusó a Óscar de pertenecer a la clica Hoover Locos Sureños HVLS, de la pandilla 18, con rango de extorsionista y función de colaborador. En su contra declararon dos de los cuatro policías que lo detuvieron. La versión que ambos dieron en el juicio fue que se encontraban realizando patrullaje preventivo en la zona, alrededor de las 10 de la noche del 21 de mayo de 2022 cuando una persona, que no quiso ser identificada, les comentó que en la colonia había un grupo de pandilleros reunidos y que no eran de la zona.

Posterior al aviso, procedieron a intervenirlos, pero huyeron del lugar a excepción de Óscar y Blanca. El primer agente en declarar dijo que tenía cinco meses de conocer a Óscar, que lo había visto pidiendo dinero a las personas, “posteando” o en bicicleta con otros miembros de la pandilla.

“Unos corrían para un lado, otros para otro lado, pero solo se dio alcance al menor que se quedó en el lugar. No había otra persona más, el menor salió caminando en ruta de los demás, no corriendo por eso fue que se logró darle alcance”, agregó.

El padre de Óscar tiene otra versión: “La forma en que la Policía dice que lo capturó es mentira, porque ellos dijeron que lo detuvieron en otro lugar, a otra hora de la noche y que estaba reunido con otros, pero eso no tiene nada que ver con lo que realmente pasó”.

Sin ninguna otra prueba que corroborara la declaración de los policías, el Juzgado de Menores de Ahuachapán determinó que las versiones de los testigos eran “concordantes” con la prueba pericial y documental.

“(Los policías) fueron enfáticos en expresar dos circunstancias importantes. Una, es que recibieron información de una persona que no quiso ser identificada por temor, y la declaración de la perito de la Policía quien, refiere que la zona donde reside el procesado y donde fue capturado tiene presencia de la pandilla 18 (…) La declaración de los testigos que se incorporaron es creíble, en tanto que al referirse al caso fueron categóricos, naturales y objetivos en los datos aportados”, sustentó el juez para otorgarle una condena de dos años y seis meses.

Es la mañana del 28 de junio y sentado en el corredor de la casa, su padre sostiene con ambas manos un cartel que carga consigo en las marchas para exigir la libertad de su hijo condenado injustamente. “No más violación a los derechos humanos, 20 meses sin saber de mi hijo”, dice el texto que su padre escribió, pues desde que fue capturado la familia no ha sabido nada de Óscar y en la última audiencia el abogado tampoco pudo verlo.

“Es como si estuviera desaparecido. Es bien duro porque todo sucedió injustamente, yo siempre lo he andado siguiendo a todos los lugares donde lo trasladaron desde su captura, trabajaba de seguridad y renuncié a mi trabajo por todas las vueltas que se deben hacer y desde Santa Ana hasta Ilobasco me lleva todo el día”, enfatiza.

Una condena revocada por una Cámara

Eran las 6 de la tarde del 14 de abril de 2022, cuando un grupo de menores de edad había dispuesto salir a jugar en una de las colonias del departamento de La Unión. El juego había empezado, cuando fueron detenidos por policías.

“Nos empezaron a revisar, nos quitaron las camisas, los calcetines, las gorras, y esas las rompieron, prácticamente nos dejaron en bóxer. Nos revisaron para ver si andábamos droga, pero nosotros no andábamos, ellos querían ponérnosla”, recuerda Kevin, uno de los seis menores de edad que fue capturado aquella tarde y que logró quedar libre después de 14 días.

Ese día también había llegado Esmeralda, una menor de 14 años compañera de Kevin y sus amigos. Él recuerda cómo los policías comenzaron a decirle que ella era “mujer de todos”. Según consta en la declaración de los hechos del expediente judicial, los agentes también le preguntaron desde cuándo mantenía una relación sentimental con uno de los menores y cuándo había sido la última vez que ambos tuvieron relaciones sexuales y a qué hora.

“Ella solo tenía a su novio que andaba ahí con nosotros y por eso la llevaron detenida”, relata Kevin.

Aunque un juzgado de menores condenó a Kevín, una cámara consideró que las pruebas fueron débiles y cargadas de contradicciones.

Además, que la prueba testimonial presentada por la Fiscalía “violenta el principio de razón suficiente, contradicción y derivación para tener por acreditada la participación del adolescente como colaborador de una agrupación ilícita”.

La situación era la misma que en los otros casos narrados por familiares de otros menores: agentes que patrullaban observaron a un grupo de personas que al verlos optaron por huir. Alcanzaron a seis de ellos y los acusaron de ser pandilleros.

La Cámara enfatizó que no hubo elementos de prueba que confirmara los testimonios de los policías. “Lo que se debe buscar es una prueba que corrobore lo manifestado por un testigo a fin de que su declaración no quede como una simple manifestación verbal considerada subjetiva”, advirtió.

Un sargento sostuvo también que desde hacía meses él daba seguimiento al caso pues el adolescente era colaborador de la pandilla de la zona y que la información la conocía por personas del lugar.

“Al no existir otros elementos de prueba que establezcan la colaboración del adolescente a este tipo de estructuras, la fundamentación y la motivación dada por el juez que declaró responsable al adolescente no se encuentra apegada a derecho”, sentenció.

Es mediodía del jueves 30 de mayo de 2024 y cerca de la calle donde los seis menores fueron capturados camina una señora de aproximadamente 55 años, dice que conoce a Kevin y que sabe que es un buen estudiante.

Los ojos se enrojecen y se llenan de lágrimas al recordarlo: “él era un buen niño, hacía un gran esfuerzo para poder estudiar, yo no sé por qué se lo llevaron. Su mamá lavaba ajeno para poder mandarlo a la escuela, así fue como hizo hasta noveno grado”, susurra, su voz se quebranta y rompe en llanto.

A un kilómetro de ese lugar está la casa de Kevin, ahora solo vive con su hermana y su abuelo debido a que a su madre la asesinaron luego que él quedó libre. Resignado dice que tuvo que dejar de estudiar después que ella murió para ayudarle a su abuelo con los gastos.

Después de la captura, cuando Kevin intentó retomar la escuela ya no pudo salvar el año, tenía muchas inasistencias.

“Yo estudiaba noveno grado, iba a la escuela por la tarde, pero mientras estuve preso perdí el año escolar, el siguiente año regresé, pero mis compañeros me molestaban que si yo era una persona mala y metido en malos pasos”, lamenta.

Sus días dentro de la cárcel tampoco fueron fáciles. Recibía dos tiempos de comida al día y podía tomar agua una o dos veces. Lo que más lamenta es haber estado separado de su familia. “Todo ese tiempo que estuve ahí no pude ver a mi familia. En la noche me sentía deprimido, a veces no comía por la misma falta que me hacían, me ponía a llorar y el día que por fin volví a la casa yo lloraba pero de emoción”, relata.

Frente a la calle donde jugaban vivían dos de los menores capturados, uno de ellos salió libre, Luis de 16 años, y el otro fue condenado, Alberto de 15 años. Su madre, Carmen, cuenta que Alberto lleva detenido un año y medio en el Centro de Inserción Social Sendero de Libertad, en Ilobasco.

El Juzgado de Menores de La Unión lo condenó a dos años de cárcel tras declararlo culpable por agrupaciones ilícitas, luego de que la Fiscalía lo acusara de tener la función de “paro” dentro de la pandilla.

Las declaraciones en juicio de los agentes fueron contradictorias. La primera relata que recibieron información a través de denuncias de la ciudadanía que en la colonia se reunían miembros de pandillas y que al realizar patrullaje preventivo dieron con el paradero de los menores y por eso los capturaron, pues no portaban uniformes que los identificaran como un equipo de fútbol cuando se disponían a jugar sobre la calle, la tarde de aquel 14 de abril.

La otra versión contó que encontraron a los “sujetos” y que procedieron a su detención “sin más que cumplir con lo establecido en la ley de encontrar a dos o más personas agrupadas”.