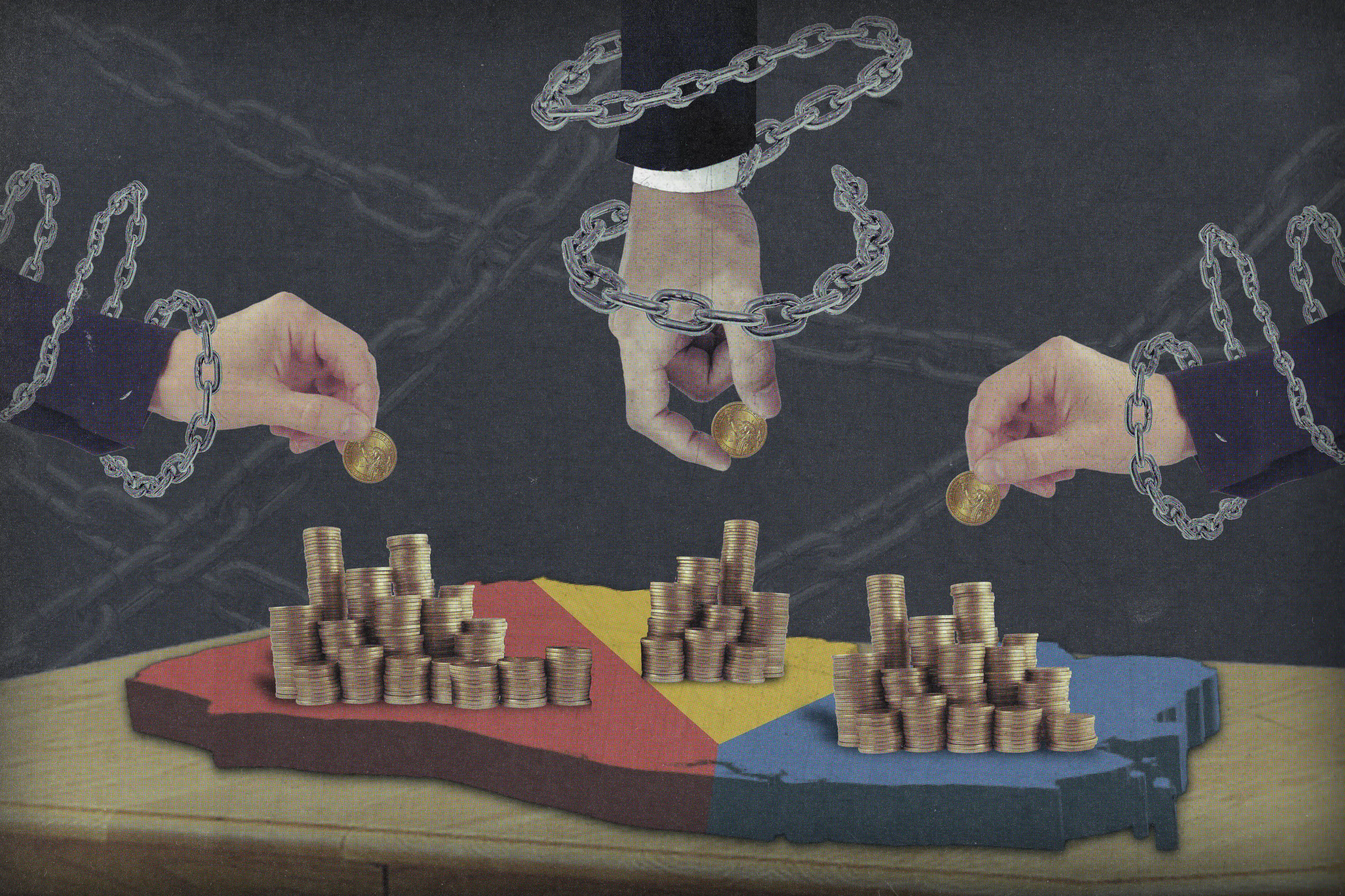

The finances of Nayib Bukele’s government have remained afloat thanks to debt totaling $7,767 million in disbursements from three types of creditors: international financial organizations (such as CABEI, IDB, IMF, CAF), international investors who bought bonds, and domestic investors – private banks and institutions in the financial sector – who bought government debt in the local market.

These $7,767 million in disbursements of “external financing” (2019-2023), which entered budgets and were spent, represent an average contribution of 20% to the national budget of El Salvador, which, in total, amounts to $39,522 million spent and settled in those five years. This data comes from financial management reports submitted by the Treasury to the Legislative Assembly, public information that allows for the conclusion that 38.3% of the disbursements of “external financing” were provided by international organizations ($2,973 million); 38.7% by international investors ($3,006 million); and 23% by local investors who also bought $1,788 million of government debt.

President Bukele controls all three branches of government, and this concentration of power has allowed him to dismantle gangs and reduce violence rates. His Achilles’ heel has been the economy and public finances. His administration has not been able to keep the government’s finances afloat without resorting to high-interest loans that compromise future budgets by having as a condition the payment of higher amortizations (installments to gradually reduce debt). One example: in 2023, interest payments included in the budget ($1,016 million) were higher than the accrued budget for the Health branch ($1,008 million). With the new debt, that expense will grow more.

Although different presidential administrations have covered a percentage of the budget with debt, the Bukele administration has taken it to the extreme: a search for creditors with lax requirements or who do not require accountability for the use of the funds they are lending. The government has opted for placing debt in the international market at usurious rates (over 10%). In addition, this administration has implemented a policy of hiding information that prevents knowing how these disbursements of “external financing” are being spent.

The Bukele administration has not implemented a tax reform that would cut unnecessary spending and increase revenue collection. Instead, as it becomes more indebted, it spends more opaquely. To maintain this practice, it has stopped honoring commitments that in previous years were met in the budgets. For example, on December 19, 2022, the Bukele administration agreed not to pay its debt to the pension fund for four years: more than $2,000 million. Although the government claims that it has not defaulted on its creditors, the truth is that it has stopped paying its debt to active workers who contribute to the AFPs every month to grow the pension fund that will pay their retirement benefits.

In addition to this measure, the suppression of Fodes (State Fund for financing municipalities) and the reduction of mayoralties (from 262 to 44 local governments) has allowed for savings of more than $800 million, redirected to an institution controlled by the Presidential House: the Directorate of Municipal Works, which is now responsible for managing one of the largest wallets for the allocation of public works contracts to construction companies.

If the government finds more “relief of this kind” – stop paying commitments such as contributions to the pension fund and eliminate financial obligations to the mayoralties – it may be that in Bukele’s second five-year term, which begins on June 1, 2024, it will increase its spending (which is much higher than its income) and maintain the same pace of indebtedness. However, the government will require putting out fires through the subscription of loans with higher interest rates to continue paying due loans and sustaining the functioning of its government.

And there are already signs: just days before the start of his second and unconstitutional presidential term, more than $2,500 million in debt is about to be signed to support President Bukele’s second five-year term. This new debt includes a bond issuance of $1,000 million in the international market at an interest rate of 12%, one of the highest post-war interest rates. The Treasury also obtained a second legislative authorization to issue another $1,500 million in bonds (another type of debt) that was known in the plenary session of the Legislative Assembly in the penultimate week of May 2024.

The Treasury provided a brief explanation of the purpose of this new indebtedness, through a piece of correspondence received on May 20. The document describes that they are requesting authorization to subscribe to this debt as part of a “liabilities restructuring strategy,” meaning a new loan to pay off other loans that are about to expire. “These credit securities, other financial instruments, and/or a combination of both will be used for general budget needs of the State and/or financing of liability management operations,” says the piece of correspondence.

The destination of the disbursements received from creditors in the National Budget is unknown, as the Treasury reserved all accounting information managed by the General Directorate of Government Accounting. The Bukele administration had promised in 2021, through a “Public Financial Sector Indebtedness Policy,” that the debt managed from 2019-2024 would only be used for strategic priorities: “the primary objective is for entities to have the necessary funds to finance public investments, in accordance with the Government’s strategic priorities, the Cuscatlán Plan, and other sector plans,” says the policy developed by the Ministry of Finance.

Loan disbursements did not serve to fulfill the Cuscatlán Plan: Bukele’s government failed to fulfill 78% of the promises in that plan, meaning 46 unfulfilled promises in public works, economy, transparency, education. The government created the Agency for Development and Nation Design on September 28, 2021, led by the American David Rivard, but to date, the plans drawn up by that office and the Council of Ministers have not made public the actions included in these “sector plans” to evaluate their level of fulfillment.

More debt, less transparency

Between 2020 and 2024, the IMF held talks with the Government of El Salvador to facilitate a fund of $1,300 million, earmarked and tied to a series of transparency recommendations and fiscal targets. Among the points that stalled an agreement with the IMF was the government’s refusal to remove Bitcoin’s recognition as legal tender – which it has held since September 2021 – and the government’s unwillingness to establish a fiscal transparency program that would allow for knowing how resources are being used.

In 2022, the government was struggling to avoid default – not being able to honor its commitments to creditors on time – and to make bond maturity payments. At the end of March that year, the government communicated to Wall Street investors its three plans – or scenarios – to obtain $4,852 million and avoid default between 2022 and 2024. Scenario two – described in the document – is called “pension reform and local debt market” and includes a list of emergency measures to be implemented in the absence of an agreement with the International Monetary Fund. The scant financial information available from the Treasury allows concluding that the government managed to buy time thanks to loan disbursements received between January 2022 and April 2024: $4,559 million (of the $7,767 million in loans disbursed in the five-year term). The fiscal adjustment with the spending cut established in the pension reform and the suppression of Fodes allowed the government to remain temporarily afloat.

How much time has the government bought while waiting for an agreement with the IMF? The Executive declared under reservation the actuarial studies of the pension reform approved on December 19, 2022. Without this information, it is uncertain to establish a date when the government will need that agreement with the IMF to cover expenses that are becoming underfinanced in the future, for example, the hole of more than $2,000 million that is being created in the pension fund due to the four-year payment moratorium. It is not clear whether the government in 2026 will extend that moratorium on payment of its debt with the pension fund.

On March 20, 2023, an IMF technical team completed its visit to El Salvador for the preparation of the Article IV Report, which usually includes a diagnosis of the state of public finances and a suggestion of measures. “The authorities did not authorize the publication of the report prepared by the staff or the press releases,” says a brief IMF statement from March 20, explaining that the Government of El Salvador opposed making transparent the information collected by that technical mission.

A statement from the visit in February 2023 and an earlier IMF report, which was not reserved, already included a series of recommendations that were not well received by the government. “We urge the authorities to reduce the scope of the Bitcoin Law, removing its legal tender status,” says one of the recommendations in that previous report.

The IMF also called for a transparency program with these components: “improve procurement procedures, including information on ultimate beneficiaries of awarded contracts”; “improve accountability of Fopromid funds”; “strengthen fiscal transparency, including the use of funds for addressing the Covid-19 emergency”; “define parameters for auditing Chivo and Fidebitcoin.”

When the Assembly with an official majority took office on May 1, 2021, one of the first actions was to strike a blow to the judiciary, by removing the magistrates of the Constitutional Chamber. They also dismissed the Attorney General. They imposed a prosecutor who shelved the investigations of a file known as Cathedral, which investigated $71 million in irregularities in food purchases with Covid-19 funds. The previous Prosecutor’s Office had raided the Ministry of Health and was investigating the management of $20 of the $31 million budget for protective equipment and medical supplies purchased during the pandemic. That same official Assembly approved an Amnesty Law for crimes that may have been committed in the management of resources to address the pandemic.

Disbursements of loans for $7,767 million

The five main international organizations for the interests of the Bukele administration have been CABEI, IDB, CAF, JICA, and the World Bank. This class of creditor has contributed $2,973 of the $7,767 million in disbursements received in the budgets from 2019 to 2023. El Faro asked CABEI, IDB, CAF, and the World Bank on May 23 if they can guarantee – with information such as audits – the proper handling of the funds disbursed to the government and also asked if they are not concerned that the government has reserved information on budget execution. Still, at the close of this note, there was no response from any of these international organizations.

Contracts with international organizations usually include transparency, anti-fraud, and anti-corruption clauses. Despite these rules, they have continued to support the government that has reserved all information on budget execution. In March 2023, El Salvador was expelled from the Open Government Partnership for dismantling its national transparency system and the absence of accountability for the use of public funds. El Faro requested an interview with Finance Minister Jerson Posada by email on May 28, and one of the topics included was whether in Bukele’s second term they would end the reservation of information on budget execution, but at the close of this note, there was no response.

The dismantling of democracy in El Salvador has had few repercussions on disbursement flows. The only significant change occurred in 2021, with CABEI, IDB, and CAF. Between 2019 and 2020, the IDB was on its way to becoming the organization that provided the most funds to the government of El Salvador to finance budget projects. However, since 2021 it has cut its contributions to the government, coinciding with the blow to the judiciary dealt by Bukele. CABEI and CAF, on the other hand, increased their contributions from that time on to the power concentration project of the Bukele clan. CABEI and CAF contributed $1,030 and $301 million, respectively.

In 2020, during the pandemic, the IMF made available to countries a special fund, and El Salvador had access to $393 million. Since then, the government has been in talks to obtain an Agreement with the IMF for $1,300 million (over three years, 2021 to 2024). The Treasury had marked on its calendar that by 2021 that agreement should already be ratified, according to an internal Treasury document that El Faro had access to. That money is key to keeping the government’s finances afloat in Bukele’s second term.

Although the IMF has halted this credit line, the World Bank has contributed $237 million for the budgets from 2019 to 2023. It was in 2022 when it contributed the most disbursements, associated with pandemic recovery expenses, of $146 million. They have also supported the first lady’s early childhood policy, Crecer Juntos, with almost $50 million.

In addition to international organizations, there are two other types of creditors whose disbursements kept the government afloat in this first five-year term: $1,788 million was contributed by local investors (private banks), and $2,788 million came from bond placements in the international market. These two creditors are most interested in the government signing an agreement with the IMF to guarantee the liquidity needed to meet their financial obligations.

Among domestic investors, the government has turned to local private banks to manage the purchase of more government debt, and the bankers’ association has joined the government’s call. “Private banks in El Salvador have confirmed that they will actively participate in this country’s issuance program, thus contributing to El Salvador’s sustainable economic growth,” says a statement from Abansa – the association of El Salvador’s private banks – published on August 24, 2023. This means that private banks will use more of the population’s deposits to buy more government debt.

The announcement of the agreement’s content did not come from the government, but from a brief statement drafted by the country’s bankers’ association: “The banks have proposed a structure for local issuances at terms of 2, 3, 5, and 7 years that will allow reducing short-term public debt levels and obtaining a better profile of El Salvador’s financial obligations due in the medium term.”

Los $7,767 millones en deuda que sostuvieron a flote al primer Gobierno de Bukele

Las finanzas del Gobierno de Nayib Bukele se han mantenido a flote gracias al endeudamiento que suma $7,767 millones en desembolsos provenientes de tres tipos de acreedores: los organismos financieros internacionales (como el BCIE, BID, FMI, Caf), los inversores internacionales que compraron bonos y los inversores nacionales -la banca privada e instituciones del sector financiero- que compraron deuda del Gobierno en el mercado local.

Estos $7,767 millones en desembolsos de “financiamiento externo” (2019-2023), que entraron a los presupuestos y se gastaron, representan un aporte promedio del 20 % al presupuesto nacional de El Salvador devengado, que en total suma $39,522 millones gastados y liquidados en esos cinco años. Estos datos provienen de los informes de gestión financiera entregados por Hacienda a la Asamblea Legislativa, información pública que permite concluir que el 38.3 % de los desembolsos de “financiamiento externo” fueron aportados por organismos internacionales ($2,973 millones); el 38.7 %, por inversores internacionales ($3,006 millones); y, el 23 %, aportado por inversores locales que también compraron 1,788 millones de deuda del Gobierno.

El presidente Bukele controla los tres poderes del Estado y esa concentración de poder le ha permitido desarticular a las pandillas y reducir los índices de violencia. Su talón de Aquiles ha sido la economía y las finanzas públicas. Su administración no ha sido capaz de mantener a flote las finanzas del Gobierno sin recurrir a créditos con tasas de interés altas que comprometen los presupuestos futuros al tener como condición el pago de amortizaciones (cuotas para disminuir de forma gradual la deuda) más altas. Un ejemplo: en 2023, los pagos de intereses incluidos en el presupuesto ($1,016 millones) fueron superiores al presupuesto devengado del ramo de Salud ($1,008 millones). Con el nuevo endeudamiento, ese gasto crecerá más.

Aunque ha sido normal que distintas administraciones presidenciales cubran un porcentaje del presupuesto con deuda, la administración de Bukele lo ha llevado al extremo: una búsqueda de acreedores con requisitos laxos o que no exigen rendición de cuentas del uso de los fondos que están prestando. El Gobierno ha optado por colocar deuda en el mercado internacional a tasas de usura (de más del 10 %). Además, esta administración ha implementado una política de ocultamiento de información que impide saber cómo se están gastando esos desembolsos de “financiamiento externo”.

La administración de Bukele no ha implementado una reforma fiscal que recorte gastos innecesarios e incremente la recaudación, sino que conforme se endeuda más, gasta más de manera opaca. Para mantener esta práctica, ha dejado de honrar compromisos que en años anteriores eran cumplidos en los presupuestos. Por ejemplo, el 19 de diciembre de 2022, la administración Bukele acordó no pagar por cuatro años su deuda con el fondo de pensiones: más de $2,000 millones. Aunque el Gobierno presume que no ha caído en impago con sus acreedores, lo cierto es que sí ha dejado de pagar su deuda con los trabajadores activos que mes a mes aportan sus cotizaciones a las AFP para hacer crecer el fondo de pensiones con el que se pagarán sus prestaciones de jubilación.

A esa medida hay que sumar la supresión del Fodes (Fondo del Estado para financiar municipalidades) y la disminución de alcaldías (de 262 a 44 gobiernos locales), que ha permitido un ahorro de más de $800 millones, reorientados a una institución que controla Casa Presidencial: la Dirección de Obras Municipales, que ahora se encarga de manejar una de las billeteras más grandes para la asignación de los contratos de obra pública a las empresas constructoras.

Si el Gobierno encuentra más “alivios de este tipo” -dejar de pagar compromisos como los aportes al fondo de pensiones y eliminar obligaciones financieras con las alcaldías- puede que en el segundo quinquenio de Bukele, que inicia este próximo 1 de junio de 2024, incremente sus gastos (que son muy superiores a sus ingresos) y mantenga el mismo ritmo de endeudamiento. Pero el Gobierno requerirá apagar fuegos a través de la suscripción de créditos con tasas más altas de interés para seguir pagando préstamos por vencer y poder sostener el funcionamiento de su Gobierno.

Y ya hay muestras: a escasos días de que inicie su segundo e inconstitucional periodo presidencial, está por suscribirse más deuda ($2,500 millones) para sostener el segundo quinquenio del presidente Bukele. Esta nueva deuda incluye una emisión de bonos de $1,000 millones en el mercado internacional a una tasa de interés del 12 %, una de las tasas de interés más altas de la posguerra. Hacienda también logró una segunda autorización legislativa para emitir otros $1,500 millones en bonos (otro tipo de deuda) que fue conocida en la plenaria de la Asamblea Legislativa de la penúltima semana de mayo de 2024.

Hacienda entregó una escueta explicación del destino de este nuevo endeudamiento, a través de una pieza de correspondencia recibida el 20 de mayo. El escrito describe que piden autorización para suscribir esta deuda como parte de una “estrategia de reestructuración de pasivos”, es decir, un nuevo crédito para pagar otros créditos que están próximos a vencer. “Estos títulos valores de crédito, otros instrumentos financieros y/o una combinación de los mismos se destinarán para necesidades generales de presupuesto del Estado y/o financiación de operaciones de manejos de pasivos”, dice la pieza de correspondencia.

El destino de los desembolsos recibidos de acreedores en el Presupuesto General de la Nación es desconocido, debido a que Hacienda reservó toda la información contable que maneja la Dirección General de Contabilidad Gubernamental. La administración Bukele había prometido en 2021, a través de una “Política de Endeudamiento del Sector Público Financiero”, que la deuda que se gestione de 2019-2024 solo se iba a usar para prioridades estratégicas: “el objetivo primordial es que las entidades cuenten con los fondos necesario para financiar inversiones públicas, acorde a las prioridades estratégicas del Gobierno, el Plan Cuscatlán y otros planes sectoriales”, dice la política elaborada por el Ministerio de Hacienda.

Los desembolsos de créditos no sirvieron para cumplir el Plan Cuscatlán: el Gobierno de Bukele incumplió el 78 % de las promesas de ese plan, es decir, 46 promesas incumplidas en obras públicas, economía, transparencia, educación. El Gobierno creó el 28 de septiembre de 2021 la Agencia de Desarrollo y Diseño de Nación, dirigida por el estadounidense David Rivard, pero a la fecha son desconocidos los planes que ha elaborado esa oficina y el Consejo de Ministros tampoco ha dado a conocer las acciones incluidas en estos “planes sectoriales” para poder evaluar su nivel cumplimiento.

Más deuda, menos transparencia

Entre 2020 y 2024, el FMI mantuvo pláticas con el Gobierno de El Salvador para facilitar un fondo de $1,300 millones, destinado y atado a una serie de recomendaciones de transparencia y metas fiscales. Entre los puntos que entramparon un acuerdo con el FMI fue la negativa del Gobierno a quitar al Bitcoin el reconocimiento como moneda de curso legal -que ostenta desde septiembre de 2021- y la falta de voluntad del Gobierno a establecer un programa de transparencia fiscal, que permita conocer cómo se están utilizando los recursos.

En 2022, el Gobierno luchaba para no caer en ‘default’ -no poder honrar sus compromisos con acreedores a tiempo- y poder hacer los pagos de vencimientos de bonos. A finales de marzo de ese año, el Gobierno comunicó a inversores de Wall Street sus tres planes -o escenarios- para obtener $4,852 millones y evitar el default entre 2022 y 2024. El escenario dos -descrito en el documento- se denomina “reforma de pensiones y mercado local de deuda” e incluye una lista de medidas de emergencia a implementar ante la falta de un acuerdo con el Fondo Monetario Internacional. La poca información financiera disponible de Hacienda permite concluir que el Gobierno logró comprar tiempo gracias a desembolsos de préstamos recibidos entre enero de 2022 y abril de 2024: $4,559 millones (de los $7,767 millones en créditos desembolsados en el quinquenio). El ajuste fiscal con el recorte de gastos establecido en la reforma de pensiones y la supresión del Fodes permitió al Gobierno mantenerse temporalmente a flote.

¿Cuánto tiempo ha comprado el Gobierno a la espera del acuerdo con el FMI? El Ejecutivo declaró bajó reserva los estudios actuariales de la reforma de pensiones, aprobada el 19 de diciembre de 2022. Sin esa información, es incierto establecer una fecha en la que el Gobierno necesitará ese acuerdo con el FMI para cubrir gastos que están quedando desfinanciados a futuro, por ejemplo, el agujero de más de $2,000 millones que se está creando en el fondo de pensiones por la moratoria de pagos de cuatro años. No está claro si el Gobierno en 2026 prorrogará esa moratoria de pagos de su deuda con el fondo de pensiones.

El 20 de marzo de 2023, un equipo de técnicos del FMI terminó su visita a El Salvador para la elaboración del Informe del Artículo IV , que suele incluir un diagnóstico de cómo están las finanzas públicas y una sugerencia de medidas. “Las autoridades no autorizaron la publicación del reporte elaborado por el staff ni los comunicados de prensa”, dice un escueto comunicado del FMI, del 20 de marzo, que explica que el Gobierno de El Salvador se opuso a transparentar la información recogida por esa misión técnica.

Un comunicado de la visita de febrero de 2023 y un informe anterior del FMI, que no fue reservado, ya incluía una serie de recetas que no fueron bien recibidas por el Gobierno. ‘Instamos a las autoridades a reducir el alcance de la Ley Bitcoin, removiendo su estatus de moneda de curso legal’, dice una de las recomendaciones de ese informe anterior.

El FMI también pedía un programa de transparencia con estos componentes: ‘mejorar los procedimientos de compras incluyendo información de los beneficiarios finales de los contratos adjudicados’; ‘mejorar la rendición de cuentas de fondos Fopromid’; ‘fortalecer la transparencia fiscal, incluido el uso de los fondos destinados para atender la emergencia del Covid-19’; ‘definir parámetros para auditar a Chivo y Fidebitcoin’.

Cuando asumió la Asamblea con mayoría oficialista, el 1 de mayo de 2021, una de las primeras acciones fue dar un golpe al órgano judicial, con la destitución de los magistrados de la Sala de lo Constitucional. También destituyeron al fiscal general. Impusieron a un fiscal que archivó las investigaciones de un expediente conocido como Catedral, que investigaba $71 millones en irregularidades en compras de alimentos, con fondos Covid-19. La Fiscalía anterior había allanado el Ministerio de Salud e investigaba la gestión de $20 de los $31 millones del presupuesto para equipo de protección e insumos médicos comprados durante la pandemia. Esa misma Asamblea oficialista aprobó una Ley de Amnistía a los delitos que pudieron haberse cometido en la gestión de recursos para atender la pandemia.

Los desembolsos de créditos por $7,767 millones

Los cinco principales organismos internacionales para los intereses de la administración Bukele han sido el BCIE, BID, CAF, JICA y el Banco Mundial. Esa clase de acreedor ha aportado $2,973 de los $7,767 millones en desembolsos recibidos en los presupuestos de 2019 a 2023. El Faro preguntó el 23 de mayo al BCIE, BID, CAF y Banco Mundial si pueden garantizar con información -como auditorías- el buen manejo de los recursos desembolsados al Gobierno y también se les preguntó si no les preocupa que el Gobierno haya reservado la información de ejecución presupuestaria, pero al cierre de esta nota no hubo respuesta de ninguno de estos organismos internacionales.

Los contratos con organismos internacionales suelen incluir cláusulas de transparencia, anti-fraude y anti-corrupción. A pesar de estas reglas, han continuado apoyando al Gobierno que ha reservado toda la información sobre ejecución presupuestaria. En marzo de 2023, El Salvador fue expulsado de la Alianza por el Gobierno Abierto, por el desmantelamiento de su sistema nacional de transparencia y por la ausencia de rendición de cuentas sobre el uso de los fondos públicos. El Faro pidió una entrevista al ministro de Hacienda Jerson Posada por correo el 28 de mayo y uno de los temas incluidos era si en este segundo periodo de Bukele pondrán fin a la reserva de información de ejecución presupuestaria, pero al cierre de esta nota no hubo respuesta.

El desmantelamiento de la democracia en El Salvador ha tenido pocas repercusiones en los flujos de desembolsos. El único cambio significativo ocurrió en 2021, con el BCIE, BID y Caf. Entre 2019 y 2020, el BID iba camino a convertirse en el Organismo que más fondos entregaba al Gobierno de El Salvador para financiar proyectos del presupuesto, pero a partir de 2021 recortó sus aportes al Gobierno, coincidiendo con el golpe al órgano judicial asestado por Bukele. El BCIE y CAF, en cambio, aumentaron sus aportes a partir de ese momento al proyecto de concentración de poder del clan Bukele. BCIE y CAF aportaron $1,030 y $301 millones, respectivamente.

En 2020, durante la pandemia, el FMI puso a disposición de los países un fondo especial y El Salvador tuvo acceso a $393 millones. Desde entonces, el Gobierno ha estado en conversaciones para obtener un Acuerdo con el FMI por $1,300 millones (a tres años, 2021 a 2024). Hacienda había marcado en su calendario que para 2021 ese acuerdo ya debía estar ratificado, según un documento interno de Hacienda al que El Faro tuvo acceso. Ese dinero es clave para mantener a flote las finanzas del Gobierno en el segundo mandato de Bukele.

Aunque el FMI ha frenado esta línea de crédito, el Banco Mundial ha aportado $237 millones para los presupuestos de 2019 a 2023. Fue en 2022 cuando más desembolsos aportó y están asociados a gastos de recuperación de la pandemia, $146 millones. También han apoyado la política de la primera infancia impulsada por la primera dama, Crecer Juntos, con casi $50 millones.

Además de los organismos internacionales, hay otros dos tipos de acreedores cuyos desembolsos mantuvieron a flote al Gobierno en este primer quinquenio: $1,788 millones fueron aportados por inversores locales (la banca privada) y $2,788 millones provinieron de las colocaciones de bonos en el mercado internacional. Son estos dos acreedores los más interesados en que el Gobierno firme un acuerdo con el FMI que garantice la liquidez necesaria para hacerle frente a sus obligaciones financieras.

Entre los inversores nacionales, el Gobierno ha recurrido a la banca privada local para gestionar que compren más deuda estatal y la gremial de banqueros se ha sumado a los llamados del Gobierno. ‘Los bancos privados de El Salvador han confirmado que participarán activamente en este programa de emisiones del país, contribuyendo de esta manera al crecimiento económico sostenible de El Salvador’, dice un comunicado de Abansa -la asociación de la banca privada de El Salvador- publicado el 24 de agosto de 2023. Eso significa que la banca privada usará más dinero de los depósitos de la población para comprar más deuda estatal.

El anuncio del contenido del acuerdo no vino del Gobierno, sino de un escueto comunicado redactado por la gremial de banqueros del país: ‘Los bancos han propuesto una estructura de emisiones locales a plazos de 2, 3, 5 y 7 años que permitirá reducir los niveles de deuda pública de corto plazo y obtener un mejor perfil de vencimientos de las obligaciones financieras de El Salvador a mediano plazo’.