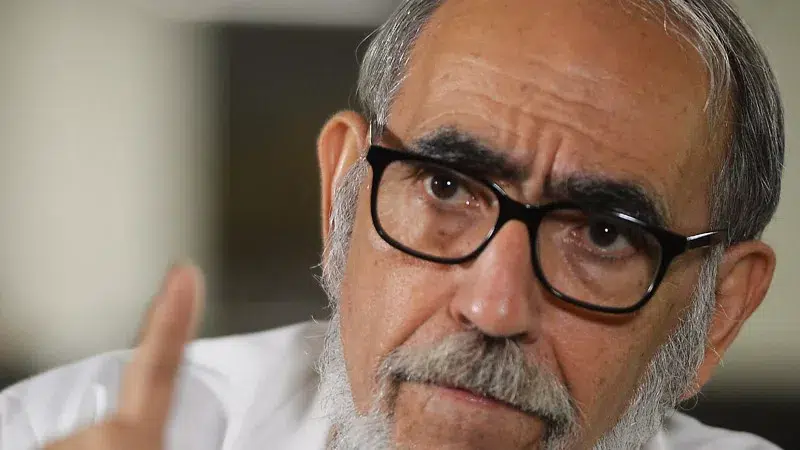

Former Salvadoran ambassador to the United States, Rubén Zamora, asserts that the reform agreement to Article 248 of the Republic’s Constitution, approved by the Legislative Assembly on April 29, aims to establish Nayib Bukele’s indefinite presidential re-election after Bukele was re-elected for a second term against the stipulations in the Magna Carta.

With this reform, the Assembly granted itself the power to make changes to the Republic’s Constitution within a single legislature: it will no longer be necessary to wait for the vote of a second Assembly to ratify constitutional reforms, as three-quarters of the lawmakers’ votes will suffice to change the Constitution. “This represents an imminent danger, we are facing the death of democracy,” considers Zamora.

The analyst and former politician also questions the 54 Nuevas Ideas lawmakers in the new legislature if they will “do what the Constitution orders them to” on June 1st, disregarding Nayib Bukele as president. He recalled that, according to Article 131 of the Republic’s Constitution, it is an attribute of the Assembly to “compulsorily not recognize the president when they continue exercising the office after their constitutional period, and to appoint an interim president.”

Zamora, who also served as El Salvador’s ambassador to the United Nations, analyzes the role of the international community in what he considers “a crisis” in the country.

“The international community has spoken in its own way,” he acknowledges, rejecting human rights violations through the state of exception.

However, he regrets that there is no clear stance from governments in the region on El Salvador’s situation in the face of Bukele’s re-election aspirations. “The United States does not have a clear policy for Central America, despite the formation of a new dictatorship,” he asserts.

Regarding the possible activation of the Inter-American Democratic Charter by the Organization of American States (OAS), suggested by the Washington Office for Latin American Affairs (WOLA), he does not find it a viable option due to the time it would take and the positions of Latin American countries concerning the nation.

“From the OAS, there has never been a call to tell a country how to reform its own Constitution,” he explains. For Zamora, “there are limitations” in the statements the OAS can make: “the words are very nice, but there has to be consensus for all member countries to sign, the words are not usually so forceful.”

What is your analysis of the approval of the reform to Article 248?

It is what they have been seeking from the beginning. The eagerness to change the Constitution goes back to the first years of Bukele’s administration, including a mandate given to Vice President (Félix) Ulloa, who formed his ad hoc team to propose constitutional reforms. All of this was a sham to try to get Bukele to be immediately re-elected, but it did not work. In the end, they opted to do it through a resolution of the Constitutional Chamber (Sala de lo Constitucional) that they themselves appointed, but this is not enough for a new term, and they know it. That is why they have now sought to do something else, which is to invent this reform to allow a single Assembly to change the Constitution. This is obviously illegal, and in the event that the new Assembly ratifies it, it is due to a desperate measure by Bukele’s Government, which does not know how to stay in power. He wanted to change the Constitution from the beginning, but since he was told no, he now carries a reform to remove this obstacle.

What is the Government’s intention in accelerating the reform process?

To be able to do whatever they want. For Bukele, the Constitution is a hindrance, and he is eliminating it with this decision. The first step is indefinite re-election, which the law prevents them from carrying out, but they will not stop there. They want a higher degree of control, and this can even be seen in what has just happened with the doctors. There is an article in the Constitution that talks about the practice of medicine and how it should be monitored by organizations made up of the same professionals. They could eliminate this, and they have done so de facto by approving a law to regulate medical specialties, where the president appoints the heads of professions. We could expect this in other areas as well. In other words, this social contract that is the Constitution, destroys it: it is a clear dictatorship.

What does this reform imply for the country?

It means that what is coming is a large number of reforms. The Constitution is falling apart; it is no longer valid; this is the most serious issue: it will be like any secondary law that can be changed from one day to the next, as the Government wishes. This represents an imminent danger; we are facing the death of democracy in the country.

Do you believe the intention is to perpetuate power over time?

To me, it is clear. Why does the Constitution bother them? Because the Constitution sets limits; for example, it states six times that he cannot serve two consecutive terms and that he cannot exercise power even one day after his term. I would like to ask the new lawmakers: what will they do with the obligation the Constitution imposes on them not to accept even one hour or one day more for someone who wants to stay in the Government?

Should they disregard him?

It is what the Constitution orders them to do; it is within the Assembly’s attributions to compulsorily not recognize the president when they continue exercising the office after their constitutional term ends and to appoint an interim president.

What implications would indefinite re-election have internationally for El Salvador?

There is something that everyone knows, and that is that the United States currently does not have a real strategy regarding its relationship with Central America. Suddenly it is pointing to Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, or rejecting some action by Bukele, especially through the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which has told him that it will not give a cent if he does not stop this Bitcoin issue. Another dictatorship in the region is serious, but there is no firm stance from the governments of the region, let alone the United States.

Do you believe the international community is not active regarding what is happening in El Salvador?

I think it is. For example, the United Nations is making proposals for what falls within its purview. Calls have been made for human rights violations in the state of exception, and strong calls have also been made in the Inter-American system. But it has reached only that far because a declaration is something that each country must assess, and the whole region is in a very difficult transition period to assume.

Do you think the reform also has implications in limiting citizens’ rights?

Yes, but it is something they are already doing. It could deepen; for example, by promoting a reform that would hinder the functioning of civil society organizations… All of this will be like in dictatorships, where what the leader says is done.

If ratified, do you think the United States will take a firmer stance?

There is a problem there. The American extreme right sees it from a migration perspective, to put an end to migration, while the Democrats know that it is a delicate issue, that migration is rejected, but they do not know what to do. Let’s also remember that they are campaigning, so it is a delicate situation. We are not a target audience for that campaign, with just 2 million Salvadorans living in the United States, we do not have an impact.

Do you believe Joe Biden’s administration has softened its stance?

I think the United States does not have a defined strategic position regarding Central America, despite the formation of another dictatorship in the region.

The Washington Office for Latin American Affairs (WOLA) suggested applying the Inter-American Democratic Charter. Are the conditions met to activate it?

The Inter-American Democratic Charter’s recourse is excellent, but the problem lies in applying it. There is a trend to talk about whether it will be applied or not; they discuss it in the Organization of American States (OAS) and sometimes apply it too late. Moreover, from the OAS, there has never been a call to tell a country how to reform its own Constitution, and it is a problem with these international documents. The words are beautiful, but since all countries must sign a consensus, the words are not so powerful. It is a weakness of this mechanism, which has a limit imposed by the member countries themselves.

Should indefinite re-election be expected to apply the Charter?

Regardless of the timing, it will be difficult to pressure to activate the Inter-American Charter. In the OAS, we are like 40 countries, but the problem is that they are not consistent, and we are separated, there are conflicts among the members themselves. The OAS Secretary, Luis Almagro, has to calculate everything very carefully because if he pushes for something like this and does not find enough support among all the countries, he will fail.

If the international community cannot influence, what options do Salvadorans have?

There may be support, but I have my doubts. I would not stake my life on the idea that someone will come out and speak out with every setback. But the responsibility here lies with the political parties, as opposition, to present themselves seriously as an option to the population.

What role does civil society have?

Currently, I have no doubt that civil society will continue to speak out. They are the first to react and must unite and strengthen. But there is definitely a political need, not for them to become politicians, but for political changes to occur. Those who should speak out are opposition leaders, people organized in political parties, but they are in a deep crisis, caused by cuts to financing, corruption cases, political persecution. But we have seen that after the elections, opposition parties have remained dormant.

“Para Bukele la Constitución es un estorbo, y lo está eliminando”: Rubén Zamora

El exembajador de El Salvador en los Estados Unidos, Rubén Zamora, asegura que el acuerdo de reforma al artículo 248 de la Constitución de la República, aprobado por la Asamblea Legislativa el pasado 29 de abril, tiene el objetivo de instaurar la reelección presidencial indefinida de Nayib Bukele, quien se reelegió para un según mandato en contra de lo establecido en la Carta Magna.

Con esta reforma, la Asamblea se recetó la facultad de hacer cambios a la Constitución de la República en una sola legislatura: ya no será necesario esperar el voto de una segunda Asamblea para ratificar las reformas constitucionales, y bastará con el voto de tres cuartas partes de los diputados para cambiar la Constitución. “Esto significa un peligro inminente, estamos ante la muerte de la democracia”, considera Zamora.

El analista y expolítico también cuestiona a los 54 diputados de Nuevas Ideas en la nueva legislatura si harán “lo que les ordena la Constitución” el 1 de junio, desconociendo a Nayib Bukele como presidente. Recordó que, según el artículo 131 de la Constitución de la República, es una atribución de la Asamblea “desconocer obligatoriamente al presidente cuando terminado su período constitucional continúe en el ejercicio del cargo, y hasta designar un presidente interino”.

Zamora, quien también fungió como embajador de El Salvador ante las Naciones Unidas, analiza el papel de la comunidad internacional ante lo que considera “una crisis” en el país.

“La comunidad internacional se ha pronunciado a su manera”, reconoce, rechazando la violación de derechos humanos a través del régimen de excepción.

Sin embargo, lamenta que no haya una postura clara de gobiernos en la región sobre la situación de El Salvador ante la aspiración reeleccionista de Bukele. “Estados Unidos no tiene una política clara para Centroamérica, a pesar de la formación de una nueva dictadura”, afirma.

Sobre la posible activación de la Carta Democrática Interamericana por parte de la Organización de Estados Americanos (OEA), sugerida por la Oficina de Washington para asuntos Latinoamericanos (WOLA), no le parece una opción viable, debido al tiempo que llevaría y las posturas de los países latinoamericanos respecto al país.

“Desde la OEA nunca se ha hecho un llamado para decirle a un país cómo debe reformar su propia Constitución”, explica. Para Zamora, “hay limitaciones” en los pronunciamientos que pueda hacer la OEA: “las palabras son muy bonitas, pero tiene que haber un consenso para que firmen todos los países miembros, las palabras no suelen ser tan contundentes”.

¿Cuál es su análisis sobre la aprobación la reforma al artículo 248?

Es lo que ellos han estado buscando desde el principio. El afán de cambiar la Constitución viene desde los primeros años de la administración de Bukele, incluso hubo un mandato que se hizo al vicepresidente (Félix) Ulloa, que hizo su equipo ad hoc para proponer reformas a la Constitución. Todo esto fue una porquería para intentar que Bukele pudiera reelegirse inmediatamente, pero no resultó. Al final, optaron por hacerlo a través de una resolución de la Sala (de lo Constitucional) que ellos mismos pusieron, pero eso no les alcanza para un nuevo periodo y lo saben. Por eso ahora han buscado hacer otra cosa, que es inventarse esta reforma para permitir que una sola Asamblea pueda cambiar la Constitución. Estoobviamente es ilegal, y en el caso de que la nueva Asamblea lo ratifique, es por una medida desesperada del Gobierno de Bukele, que no sabe cómo hacer para mantenerse en el poder. Él quería el cambio de la Constitución desde el principio, pero como se le dijo no, ahora lleva una una reforma para quitar este freno.

¿Cuál es la intención del Gobierno al acelerar el proceso de reformas?

Poder hacer lo que quieran. Para Bukele la Constitución es un estorbo, y lo está eliminando con esta decisión. El primer paso es la reelección indefinida, que la ley les impide, pero no se va a quedar ahí. Quieren un grado de control mayor, y eso se ve hasta en lo que acaba de pasar con los médicos. Hay un artículo en la Constitución que habla sobre el ejercicio de la profesión médica, y cómo debe ser vigilado por organismos conformados por los mismos profesionales. Esto podrían eliminarlo, y lo han hecho de facto aprobando una ley para regular las especialidades médicas, donde es el presidente el que nombra a los jefes de las profesiones. Esto podríamos esperarlo también en otras áreas. En otras palabras, ese contrato social que es la Constitución, la destruye: es una clara dictadura.

¿Qué implica esta reforma para el país?

Eso significa que lo que va a venir es una gran cantidad de reformas. La Constitución se desbanca, ya no vale, eso es lo más grave: va a ser como cualquier ley secundaria que se puede cambiar de un día para otro, según quiera el Gobierno. Esto significa un peligro inminente, estamos ante la muerte de la democracia en el país.

¿Cree que la intención entonces es perpetuarse en el poder?

Para mí es claro. ¿Por qué les molesta la Constitución? porque la Constitución les pone límites, por ejemplo, al decir seis veces que él no puede estar dos veces consecutivas, y que no puede ejercer el poder ni un día más después de su mandato. Yo quisiera preguntar a los nuevos diputados ¿qué van a hacer con la obligación que les pone la Constitución de no aceptar ni siquiera una hora o un día más al que se quiere quedar en el Gobierno?

¿Deberían desconocerlo?

Es lo que les ordena la Constitución, está en las atribuciones de la Asamblea desconocer obligatoriamente al presidente cuando terminado su período constitucional continúe en el ejercicio del cargo, y hasta designar un presidente interino.

¿Qué implicaciones tendría una reelección indefinida a nivel internacional para El Salvador?

Hay algo que todos saben, y es que Estados Unidos en este momento no tiene una estrategia real sobre su relación con Centroamérica. De repente está señalando a Daniel Ortega, en Nicaragua; o rechaza alguna acción de Bukele, sobre todo a través del Fondo Monetario Internacional (FMI), que le ha dicho que no dará un centavo si no deja esto del Bitcoin. Otra dictadura en la región es grave, pero no hay una postura firme de los gobiernos de la región, y mucho menos de Estados Unidos.

¿Considera que la comunidad internacional no está activa en relación a lo que está sucediendo en El Salvador?

Yo creo que sí lo está. Por ejemplo Naciones Unidas está haciendo planteamientos de lo que le toca. Se han hecho llamados por la violación de los derechos humanos en el régimen de excepción, fuertes llamados también en el sistema interamericano. Pero ha llegado hasta ahí, porque una declaración es algo que cada país debe valorar, y toda la región está en un período de transición muy difícil de asumir.

¿Cree que la reforma también tenga implicaciones en la limitación de derechos ciudadanos?

Sí, pero es algo que ya están haciendo. Puede profundizarse, por ejemplo, al promover una reforma que para obstaculizar el funcionamiento de organizaciones de sociedad civil… Todo esto va a ir siendo como en las dictaduras, donde se hace lo que dice el líder.

De ratificarse, ¿cree que Estados Unidos tome una postura más firme?

Ahí hay una problemática. La extrema derecha norteamericana lo ve desde una perspectiva de migración, para acabar con la migración; mientras que los demócratas saben que es un tema delicado, que se rechaza la migración, pero no saben qué hacer. Recordemos además que están en campaña, entonces es una situación delicada. No somos un público objetivo para esa campaña, con apenas 2 millones de salvadoreños residentes en Estados Unidos, no tenemos incidencia.

¿Considera que la administración de Joe Biden ha ablandado su postura?

Yo creo que Estados Unidos no tiene una posición estratégica definida respecto a Centroamérica, a pesar de la formación de otra dictadura en la región.

La Oficina de Washington para Asuntos Latinoamericanos (WOLA) sugirió que se aplique la Carta Democrática Interamericana. ¿Se cumplen las condiciones para activarla?

El recurso de la Carta Democrática Interamericana es muy bueno, pero el problema es al momento de aplicarlo. Hay una tendencia a hablar sobre si se aplicará o no, lo discuten en la Organización de Estados Americanos (OEA) y a veces lo han aplicado ya tarde. Además, desde la OEA nunca se ha hecho un llamado para decirle a un país cómo debe reformar su propia Constitución, y es un problema que hay con estos documentos internacionales. De palabras son muy bonitas, pero como tiene que haber un consenso para que firmen todos los países, las palabras no son tan contundentes. Es una debilidad de este mecanismo, que tiene un límite impuesto por los mismos países miembros.

¿Debería esperarse la reelección indefinida para aplicar la Carta?

Independientemente del momento, será difícil presionar para activar la Carta Interamericana. En la OEA somos como 40 países, pero el problema es que no son coherentes, y estamos separados, hay conflictos entre los mismos miembros. La secretaría de la OEA, de Luis Almagro, tiene que calcular todo muy bien, porque si él empuja una cosa de estas y no va a encontrar el suficiente respaldo entre todos los países, va a fracasar.

Si la comunidad internacional no puede incidir, ¿qué opciones tienen los salvadoreños?

Puede que haya un apoyo, pero tengo mis dudas. No pondría la mano al fuego para decir que va a salir alguien a pronunciarse en cada retroceso. Pero la responsabilidad aquí es de los partidos políticos, como oposición, de presentarse seriamente como una opción ante la población.

¿Qué rol tiene la sociedad civil?

Actualmente, no tengo ninguna duda que seguirá pronunciándose la sociedad civil. Son los primeros en reaccionar y deben unirse y fortalecerse. Pero definitivamente hay una necesidad política, no de que ellos se hagan políticos, si no de que haya cambios políticos. Quienes deberían pronunciarse son los líderes de la oposición, gente organizada en partidos políticos, pero están en una crisis profunda, provocada por los recortes al financiamiento, los casos de corrupción, la persecusión política. Pero hemos visto que después de las elecciones los partidos de oposición se han quedado como dormidos.