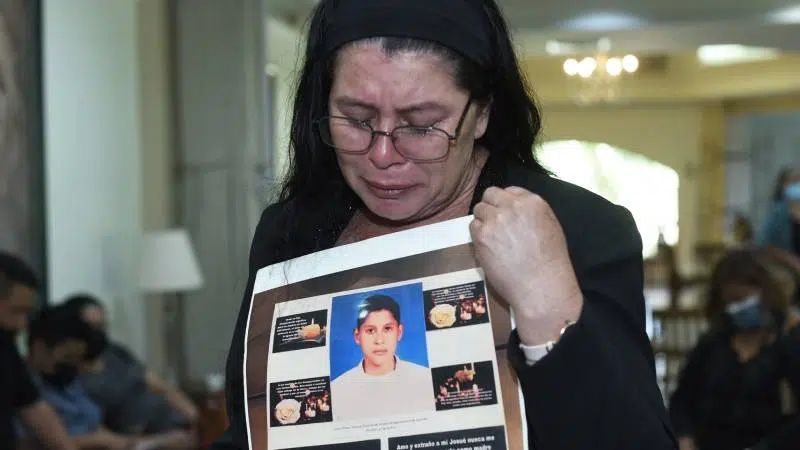

Although the Salvadoran State has tools for searching for missing persons, organizations involved in the area and in human rights matters point out that they have not been used effectively to solve cases and find victims.

The recent report “Forced or involuntary disappearances” by the Due Process Foundation (DPLF), the Passionist Social Service (SSPAS), Cristosal, the Human Rights Institute of the UCA (Idhuca), the Foundation for Studies for the Application of Law (FESPAD), and ORMUSA questions that to date in the country, there is no reliable and updated registry of missing persons and that when the search begins, it is done under the presumption of death.

Likewise, they question that the search is not carried out immediately. The report denounces that a waiting time is required to report the disappearance, contrary to current legal provisions.

“According to testimonies from relatives, the Prosecutor’s Office and the Police continue to require them to wait 24 or even 72 hours before filing a report, or they tell them that their relatives “will reappear” or that they are with their partners, among other disqualifications,” they indicate in the document.

After the waiting period, both prosecutors and police officers send the reporting families directly to the Legal Medicine Institute (IML) or hospitals to verify that the missing person has not been murdered. “Authorities in El Salvador seem to presume, without prior investigation, that the victim has been murdered,” denounce the organizations.

Regarding disappearances at the hands of the State, the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office (PDDH) received 54 complaints of forced disappearance of persons from January 2022 to December 2023. Of these, 40 correspond to men (74.07%) and 14 to women (25.93%).

However, not all complaints received by the PDDH refer to current events: four occurred in the 90s; five between 2016 and 2018; and 45 between 2019 and 2023.

In addition, the signing organizations have documented 327 complaints of forced disappearance that have occurred since the beginning of the state of exception in March 2022. In this context, they identify at least three patterns of disappearances, especially short-term disappearances.

The first form is when people are detained by state agents (police or military) in public places and in front of witnesses, with a refusal to acknowledge the arrest and their whereabouts; days, weeks, or months later, due to the insistence of the families, the people are located in detention centers. However, despite being located, information about their situation is scarce and the detainees are mostly incommunicado.

The second form consists of cases of people detained by state agents in public places and in front of witnesses, with a refusal to acknowledge the arrest and their whereabouts. Despite the insistence of the families and the filing of habeas corpus, there is no news of them.

And third, the cases of people detained by state agents in public places and in front of witnesses, there is an acknowledgment of the arrest and after days, weeks, or months due to the insistence of the families, the people are located in detention centers. However, later, it is learned that the people lost their lives in state custody, and the bodies of some of them are found with signs of torture and mistreatment.

The State’s response

In the last trial between Salvadoran human rights organizations against the Salvadoran State before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), government Human Rights Commissioner Andrés Guzmán intervened, stating that they did not recognize such figures; to which the Commission argued that the fact that they rejected them does not mean they do not exist.

In the case of disappearances committed by non-state agents, although they have been occurring for more than two decades, the state response has been “slow and still faces several challenges,” notes the report.

The organizations recall that a challenge related to the lack of information on the total universe of disappearance victims was pointed out by the IACHR: “No state institution has exact data on missing persons.”

In addition, they criticize the disparity of data on missing persons depending on the institution in question.

“That is, there are no global data that the State has systematized. One factor that hinders the registration of cases is that the legal classification of the facts is not always adequate. In many cases, the Police or the Prosecutor’s Office register disappearances as ‘deprivation of liberty’ or ‘kidnapping’,” the organizations pointed out.

They recall the occasion in which, at a session with the Committee against Torture (CAT) of the Prosecutor’s Office, held in November 2022, the Public Prosecutor’s Office reported that between 2019 and March 2022, there were 551 disappearances of persons and 1,229 cases of deprivation of liberty. However, the National Civil Police (PNC) reported 6,932 missing persons between the beginning of 2019 and June 2022.

From the second half of 2022, the PNC did not provide complete information on disappearances, claiming that it is under reserve.

The Prosecutor’s Office, on the other hand, reported 6,435 missing persons between the beginning of 2019 and the end of 2021. Then, from 2022, the information was declared non-existent.

“It is important to stress the discrepancies in the information of both institutions. Since there is no unified database, there is no coincidence in the number of missing persons registered in the 2019-2021 period,” the organizations lamented.

Missing women and girls

There is an association between the disappearances of women and femicides, which stems from a criminal practice adopted and perfected by gangs and emulated by individuals and state agents, protected by the massiveness and impunity surrounding these events, according to the report.

After several cases documented by the organizations, it was possible to identify the modalities or patterns of disappearance of women.

The first modality is that of a group, committed by gangs associated with femicide risk. In these cases, the gangs aim to kill women or girls and erase any trace of their existence.

The second way these crimes are committed is by people in the close environment associated with the femicide risk. In this case, partners, ex-partners, and people close to the victims are involved, with or without ties to criminal groups, who use disappearance to cover up a femicide.

The third one is the disappearances committed by organized crime associated with human trafficking networks for sexual exploitation purposes and those committed by trafficking networks in migration routes.

Finally, the report mentions the modality of women who “must disappear” to escape contexts that make them vulnerable to some type of violence.

Organizaciones piden creación de un registro de personas desaparecidas

Aunque el Estado salvadoreño cuenta con herramientas para la búsqueda de personas desaparecidas, organizaciones vinculadas en el área y en materia de derechos humanos, señalan que no se han utilizado de forma efectiva para solucionar los casos y encontrar a las víctimas.

El reciente informe “Desapariciones forzadas o involuntarias” de la Fundación para el Debido Proceso (DPLF), el Servicio Social Pasionista (SSPAS), Cristosal, el Instituto de Derechos Humanos de la UCA (Idhuca), la Fundación de Estudios para la Aplicación del Derecho (FESPAD) y ORMUSA cuestiona que a la fecha en el país no exista un registro confiable y actualizado de personas desaparecidas y que al iniciarse la búsqueda, se realiza bajo la presunción de muerte.

Asimismo, cuestionan que no se realiza la búsqueda de manera inmediata. El informe denuncia que se exige tiempo de espera para denunciar la desaparición, contrario a las disposiciones legales vigentes.

“De acuerdo con testimonios de familiares, la Fiscalía y la Policía les siguen exigiendo que esperen 24 o hasta 72 horas antes de presentar una denuncia, o les dicen que sus familiares “ya van a aparecer” o que andan con sus parejas, entre otros descalificativos”, señalan en el documento.

Transcurrido el plazo de espera, tanto fiscales como policías envían a las familias denunciantes directamente al Instituto de Medicina Legal (IML) o a hospitales para verificar que la persona desaparecida no haya sido asesinada. “Las autoridades en El Salvador parecen presumir, sin previa investigación, que la víctima ha sido asesinada”, denuncian las organizaciones.

Sobre las desapariciones a manos del Estado, la Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos (PDDH) desde enero de 2022 hasta diciembre de 2023 recibió 54 denuncias de desaparición forzada de personas. De ellas, 40 corresponden a hombres (74.07 %) y 14 a mujeres (25.93 %).

Sin embargo, no todas las denuncias recibidas por la PDDH se refieren a hechos actuales: cuatro ocurrieron en los años 90; cinco entre 2016 y 2018; y 45 entre el 2019 y el 2023.

Además, las organizaciones firmantes han documentado 327 denuncias de desaparición forzada que habrían ocurrido desde el inicio del régimen de excepción en marzo de 2022. Bajo este contexto, identifican al menos tres patrones de desapariciones, sobre todo desapariciones de corta duración.

La primera forma es cuando las personas son detenidas por agentes del Estado (policías o militares) en lugares públicos y frente a testigos, con la negativa a reconocer la detención y su paradero, días, semanas o meses después por la insistencia de las familias, las personas son ubicadas en centros de detención. Pero a pesar de ser ubicadas, la información sobre su situación es escasa y las personas detenidas están mayormente incomunicadas.

La segunda forma son casos de personas detenidas por agentes del Estado en lugares públicos y frente a testigos, con la negativa a reconocer la detención y su paradero. Pese a insistencia de las familias e interposición de habeas corpus, no se tiene noticia de ellas.

Y tercero, los casos de personas detenidas por agentes del Estado en lugares públicos y frente a testigos, hay un reconocimiento de la detención y tras días, semanas o meses por la insistencia de las familias las personas son ubicadas en centros de detención. Pero, posteriormente, se tiene noticia que las personas perdieron la vida bajo custodia del Estado y los cuerpos de algunas de ellas son hallados con señales de tortura y malos tratos.

La respuesta del Estado

En el último juicio entre organizaciones de derechos humanos salvadoreñas contra el Estado salvadoreño ante la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (CIDH), intervino el comisionado gubernamental de Derechos Humanos, Andrés Guzmán, quien señaló que dichas cifras no las reconocían; a lo que la Comisión alegó que el hecho que las rechazaran no significa que no existieran.

En el caso de desapariciones cometidas por agentes no estatales, pese a que llevan más de dos décadas de estar ocurriendo, la respuesta estatal ha sido “lenta y aún enfrenta varios desafíos”, señala el informe.

Las organizaciones recuerdan que un desafío relacionado con la falta de información sobre el universo total de víctimas de desaparición fue señalado por la CIDH: “Ninguna institución del Estado maneja un dato exacto sobre personas desaparecidas”.

Además, reprochan la disparidad de datos de personas desaparecidas dependiendo de la institución de que se trate.

“Es decir, no hay datos globales que el Estado haya sistematizado. Un factor que dificulta el registro de los casos es que la calificación jurídica de los hechos no siempre es adecuada. En muchas ocasiones, la Policía o la Fiscalía registran las desapariciones como ‘privación de libertad’ o ‘secuestro’”, señalaron las organizaciones.

Retoman la ocasión en que en una sesión con el Comité contra la Tortura (CAT) de la Fiscalía, realizada en noviembre de 2022, el Ministerio Público reportó que entre 2019 y marzo de 2022 se registraron 551 desapariciones de personas y 1,229 casos sobre privaciones de libertad. Pero, por su parte, la Policía Nacional Civil (PNC) reportó 6,932 personas desaparecidas entre inicios de 2019 y junio de 2022.

A partir del segundo semestre de 2022, la PNC no entregó información completa relativa a desapariciones, alegando que se encuentra bajo reserva.

La Fiscalía por otra parte, reportó 6,435 personas desaparecidas entre inicios de 2019 y finales de 2021. Luego, a partir del año 2022, la información fue declarada inexistente.

“Es importante recalcar las discrepancias en la información de ambas instituciones. Debido a que no existe una base de datos unificada, no hay coincidencia en el número de personas desaparecidas registradas en el periodo 2019-2021”, lamentaron las organizaciones.

Mujeres y niñas desaparecidas

Existe una asociación entre las desapariciones de mujeres y los feminicidios, que se deriva de una práctica criminal adoptada y perfeccionada por las pandillas y emulada por particulares y agentes del Estado, amparados en la masividad e impunidad que rodea estos hechos, según el informe.

Tras varios casos documentados por las organizaciones, se consiguió identificar las modalidades o patrones de desaparición de mujeres.

La primera modalidad es la de grupo, cometida por pandillas asociadas a riesgo feminicida, en estos casos las pandillas tienen como fin asesinar a las mujeres o a las niñas y borrar toda la evidencia.

Rastro de su existencia.

La segunda forma en que se cometen esos crímenes es por personas del entorno cercano asociadas al riesgo feminicida. En este caso, están vinculadas las parejas, exparejas y personas del entorno cercano a las víctimas, con o sin vínculos con grupos criminales, que utilizan la desaparición para encubrir un feminicidio.

La tercera son las desapariciones cometidas por crimen organizado asociadas a redes de trata de personas con fines de explotación sexual, y las cometidas por redes de tráfico en la ruta migratoria.

Finalmente, señala la modalidad de las mujeres que “deben desaparecer”, para huir de contextos que las vuelven vulnerables de algún tipo de violencia.