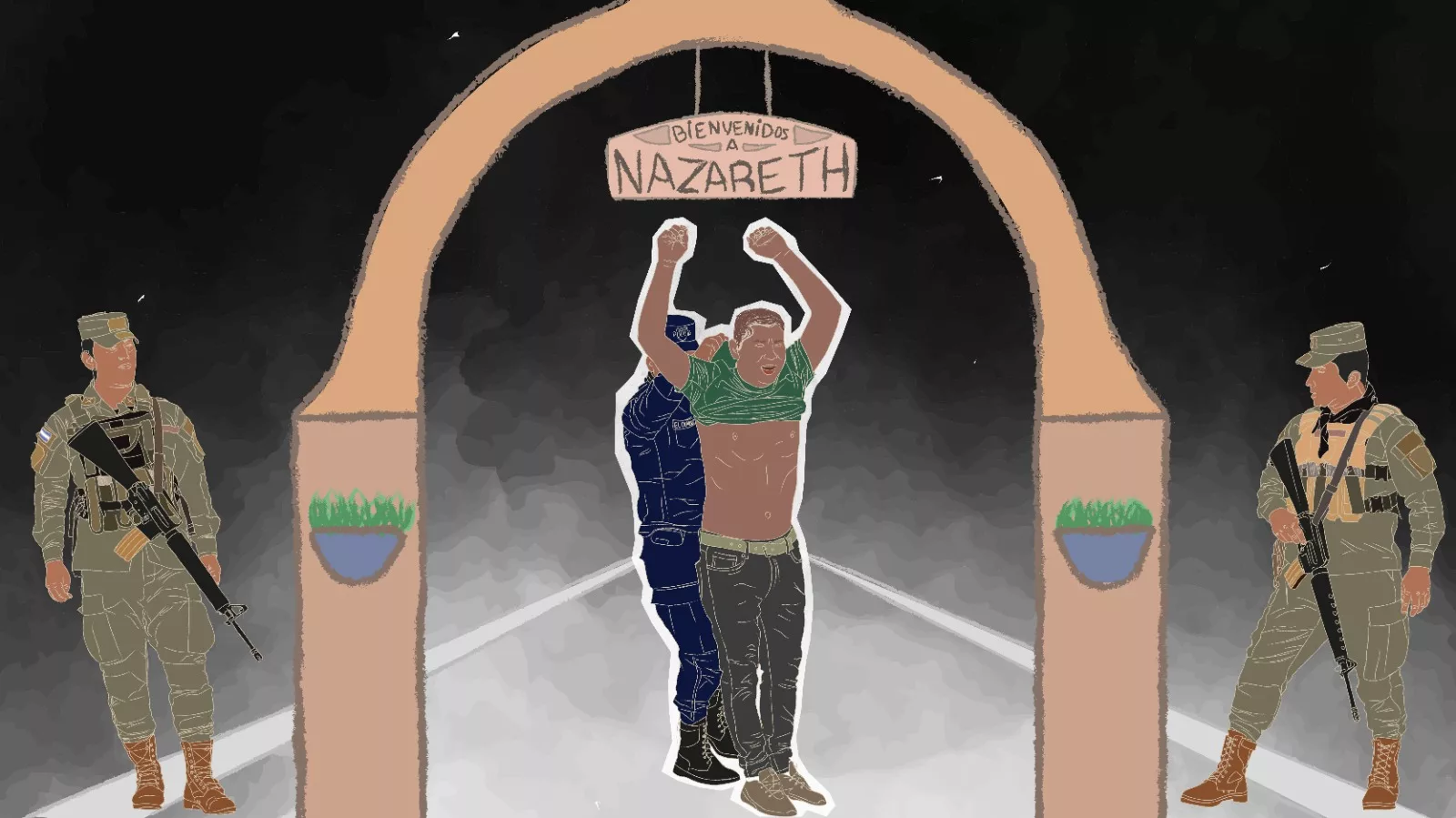

The sun was starting to set on Friday, July 15, 2022, when Elías was returning home after 12 hours of work at a fast-food restaurant on the outskirts of the Metropolitan Area of San Salvador. The motorcycle he had begun paying for a couple of months earlier was limping along a rural road that led him to a village just 5 miles south of the Salvadoran capital. Elías zigzagged and alternated accelerations with braking to dodge the craters of those pavement ruins. The 24-year-old was riding with the tranquility of someone who owes nothing, but shortly after passing under the arch that reads “Welcome to Nazareth,” he became uneasy when he saw a figure by the side of the road who raised his hand to order him to stop. It was The Devil, dressed in dark blue, accompanied by two other figures dressed in olive-green.

That trio was there officially to search for gang-related tattoos, firearms, or a unique identity document (DUI) that would reveal a gang-related past among those people they detained. Unofficially, there was also the possibility that they were only looking to meet the capture quota demanded by President Nayib Bukele’s government of the National Civil Police since the state of emergency began in March 2022, regardless of whether the person arrested is a gang member or not. The Devil and his companions had their checkpoint in an area historically disputed by the Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 gangs, and given the intense gang activity in the area, it was perhaps a good place to try to catch a “terrorist.”

The first part of the police inspection ended without any surprises: Elías had no gang-related tattoos, and his DUI number led to no criminal record for which he could be detained. Everything seemed fine until The Devil commented that he found it suspicious that one of Elías’s two cell phones was discharged. That was the sole reason he decided to confiscate it and promised to return it after reviewing it and verifying that the phone did not contain incriminating information. Elías disagreed but knew that in those days, there were plenty of arbitrary agents who could send anyone to prison for less than the claim of a cell phone. And although Elías felt robbed, he thought at least he could continue his journey home. And so he did.

The following day, Elías reported The Devil to the National Civil Police for aggravated theft. He had no idea that turning to the institution responsible for preventing and combating crime would not only mean the end of his peace but also his exile. Because The Devil, furious, would arrive a day later to announce to Elías’s mother his intention to harass and threaten them to such an extent that the young man would have no alternative: “He’ll have to get the hell out of here,” he would declare.

Nazareth is almost invisible among the coffee plantation-covered hills in the municipality of Huizúcar and has a water supply coveted by those who build dozens of residential complexes and shopping centers in neighboring municipalities. Nazareth has no shortage of water or electricity, but getting an internet or phone signal is little short of a miracle.

When you search for “Nazareth village” on Google, most of the information from the last ten years is about extortion, disappearances, forced displacement, murders, and gangs…

No one at the Huizúcar city hall can say with certainty how many people live in the village. In the words of those from Nazareth, it is a place that matters only to those who live there and that today, with the state of emergency, the threat to the lives of its inhabitants has only changed sides: it has moved from the gangs to the uniformed.

Elías is perhaps the typical young man who unfairly carries the stigma of a potential gang member. And, for The Devil’s criteria, Elías can’t be anything but a gang member: he’s 24 years old, with the aggravating factor of having two cell phones. And an even bigger aggravating factor: one of the cell phones is discharged. Elías has no tattoos, a violent or angry demeanor, or a profile in the National Civil Police identifying him as a gang member or gang sympathizer. And now, two days after the encounter on the street, Elías hears The Devil’s voice again:

“Tell him to come out, or else, I will keep a close eye on him, and he’ll have to get the hell out of here.”

Elías’s mother receives the threat at her home on the afternoon of July 17, 2022, from officer José Roberto Amaya Zelaya, dubbed The Devil by some members of the community because they consider him wicked and abusive. Elías’s mother has come out to try to contain that violent torrent dressed as a police officer and stands in the doorway of her house, like a barricade of flesh and bone, defiant, trusting that the law that this man should enforce and uphold is on her and her son’s side.

The officer complains that Elías has reported him for arbitrarily taking his cell phone. And as the woman resists, The Devil, with a gun on his waist, decides to show her the most powerful weapon an unscrupulous police officer carries in these days of a state of emergency: if the young man doesn’t come out, he’ll write a false profile presenting her son as a gang member and arrest him.

The Threat

The group looking for Elías on July 17 is the same as the one he met on the day of the checkpoint: The Devil and two soldiers traveling in an off-road vehicle now parked on the street. The Devil stopped the vehicle in front of the path that leads to Elías’s house and walked a few meters between rocks. Although the dogs alerted him to the unknown presence, The Devil forced his way in as if he owned the property or was carrying a search warrant and walked between barbed wire and lumber.

With the dogs’ alert, Elías’s mother came out to see what was happening and immediately understood the situation.

“Tell your son to come out,” he insists, and the woman, fearing an arbitrary arrest, replies no.

Elías’s mother reinforces the human barricade with a broken armchair she once thought of using to prevent the dogs from entering or leaving. She knows that her son reported a police officer and that it is that same man responsible for law enforcement who is coming to threaten her now. As the threat of forcing him to leave Nazareth does not work, The Devil, challenged by the woman’s resistance, raises the stakes:

“If he doesn’t come out, I’ll create a profile and take him to jail along with his phone,” he warns.

Thus, The Devil explains the power that some police officers believe they have in the midst of an atmosphere of suspended citizens’ rights and stimulated police abuses generated under the shadow of the state of emergency.

“Creating a profile” for a citizen means setting up a fake police record with false information about the gang or criminal organization they belong to in order to justify their capture. Elías is on the verge of having The Devil create that false biography for him.

“I’m not stealing the phone, but I won’t give it to him unless he comes out…”

The policeman thinks of nothing else but getting Elías to leave his house and now tries to persuade him with the bait of recovering his cell phone. But Elías himself has to come and get it, in this lonely place where there are no nearby people to help him or his mother.

Elías will not come out. He knows that coming out would mean jail and probably death in prison, but the uniformed man is persistent. Elías can’t stand the tension and breaks into tears, hidden behind the door, leaning against the doorframe.

After long minutes of insistence, The Devil resigns himself to the fact that, for this time, his arrogance will not be victorious, but he makes it clear that Elías will never be able to live there again.

“I know I’ll see him again… or else, let him get the hell out of here…”

The Devil prepares to leave when he hears a tearful Elías, who has gathered the courage to challenge his perverse logic:

“You can’t take me because I haven’t done anything.”

The Devil knows that Elías is right, but he immediately exposes how a mechanism plagued by arbitrariness works, probably the same one thanks to which Nayib Bukele’s government has imprisoned one in every 100 inhabitants of El Salvador in this anti-terrorist crusade that has been going on for almost two years and admitted to the imprisonment of at least 7,000 innocent people by August 2023.

“If I want to, even if I don’t have a profile right now, I can put you in jail because I know what I’m doing.”

When he says that he knows what he’s doing, he’s not saying that he’s doing the right thing, but rather what his whim dictates. And he adds some details suggesting that the pieces of the system are designed to make all this illegality work like an efficient machine:

“I write a report to the head of the DIC (Division of Criminal Investigation), and he immediately and instantly supports me.”

This kind of confession was too much for Elías’s ears because by then, numerous citizen complaints about arbitrary PNC procedures in the name of the state of emergency had become known: a legislative decree modeled by President Bukele that served to protect bad cops who arbitrarily use police records, which often do not detail but do mark a person’s gang membership.

The creation of police records is the responsibility of Police Intelligence based on the criminal record of suspected individuals, but during the days of the state of emergency, records began to abound based solely on people’s appearance or the mood of the officers. Some don’t even have a creation date. In any case, the Prosecutor’s Office now includes interviews with the capturing police officers as evidence. Those police officers who, like The Devil, may be the architects of baseless records.

A significant part of the success of the state of emergency rests on this methodology that has allowed the police to capture more than 75,000 people, mostly accused of the crime called illicit groups. In August 2023, Security Minister Gustavo Villatoro revealed that until then, 7,000 people had been released after the system concluded that there was no evidence of gang involvement. Tacitly, the regime admitted that it had locked up thousands of innocent people accused of being gang members for months. If Elías had not resisted The Devil’s demands that July afternoon in 2022, he might not have had the opportunity to choose the path he eventually had to take: forced exile.

The dilemma that the state of emergency has posed to thousands of people harassed by police and military forces is that they are forced to choose between two misfortunes: either go to prison without any legal guarantees or leave. That is, to risk ending up forgotten and dying in Bukele’s dungeons or merely being uprooted.

As both the press and human rights organizations have noted, the sentence against an innocent person who encounters the state of emergency begins on the street when they face the “street judge” – the police officer. A nickname coined by the head of the institution, Mauricio Arriaza Chicas, in February 2023, to refer to police officers.

Arriaza is a police chief whose work has not necessarily been characterized by offering guarantees of respect for human rights or ensuring the correct functioning of the units under his command. For example, between 2016 and 2018, he was under scrutiny as head of the Specialized Police Areas when several of his subordinates were implicated in extermination groups. One of the agents from the Police Reaction Group killed fellow agent Carla Ayala, and several of her colleagues were prosecuted because they did nothing to prevent the femicide or arrest the perpetrator, or because they facilitated his escape.

By October 31, 2023, the human rights organization Cristosal had documented 5,495 police abuses since the state of emergency began in March 2022. More than half of these cases were arbitrary arrests.

On September 14, 2023, a GatoEncerrado team went to the Huizúcar police station, south of San Salvador, to try to talk to officer José Roberto Amaya Zelaya. The chief of the station attended. When the reason for the visit was explained, he asked if those “problems in Nazareth” that this newspaper wanted to question the police officer about were related to the occasion when The Devil had been in prison. New information for the journalistic team, although the chief did not provide details about that case. He then explained that on that day, José Roberto Amaya Zelaya was off duty but did facilitate the team’s communication with the officer in case he agreed to give statements.

As a result of the cell phone case with Elías, The Devil has a stain on his record, as stated in the complaint filed with the Police Internal Affairs Unit.

The Internal Affairs Unit belongs to the Professional Responsibility Secretariat of the Police General Directorate. This secretariat also oversees the Disciplinary Investigation, Control, and Human Rights units. If a police officer has committed a disciplinary breach, their case is referred to the Disciplinary Investigation Unit, but if the case is of a criminal nature, it is the responsibility of the Internal Affairs Unit to investigate it in coordination with the Prosecutor’s Office.

A PNC source assured GatoEncerrado that this case had reached the Prosecutor’s Office. GatoEncerrado asked the Zaragoza Prosecutor’s Office about The Devil’s case, where they responded that they could not provide information. However, they did mention that the officer already had several complaints for similar situations to the one Elías reported.

In an attempt to obtain information on the progress of the case against The Devil, GatoEncerrado made a visit and two phone calls to the head of the Heritage Unit of the Zaragoza Prosecutor’s Office in La Libertad, Ricardo Emilio Cruz, but all three attempts were fruitless.

And until the end of 2023, The Devil continued to work and disturb the community of Nazareth.

The Devil Returns

Three months after officer José Roberto Amaya Zelaya broke into Elías’s and his mother’s home, his harassment and threats continued. The Devil is persistent. In mid-October, he threatened again, but this time not Elías.

“Has your brother come?” The Devil asks a young woman on the afternoon of October 15, 2022.

The brother he is asking about is Elías, and the woman is Ana. Ana remains silent.

“Are you not going to speak? If you don’t say anything, we’ll take you to jail.”

Ana dares to whisper a brief response.

“He’s not here. Last time you told him to leave… and he left.”

Those words telling the story of Elías’s forced displacement should perhaps be enough for The Devil to celebrate his victory. But no. Not even that quenches his thirst. He probably wants her to tell him exactly where the young man is today.

“Really?… Well, we’re going to take you instead. Give me your DUI!”

Ana feels a chill running through her body and falls silent for a few seconds. The armed man demands that she show him her unique identity document and announces that he will arrest her. Because he can.

Three months earlier, her brother had chosen exile over the certain risk of imprisonment, and now she suffers the same threat. History repeats itself.

Ana can’t remember that day without her voice trailing off. And when she recounts that encounter, her daughter, who has just started going to school, runs to hide because she is terrified.

Ana wanted to explain to The Devil that Elías’s voice was no longer heard in that house. That he didn’t show up, not even sneakily. That if he checked the house, he would see that only his bed, a couple of rags, and the memory of him returning at night, exhausted, after his long hours of work were left. Ana wanted to tell him that Elías had fled. That to protect his life, her brother had given up everything that actually made up his life.

In the end, The Devil stops grumbling but not threatening. He returns the DUI and tells her, “I’ll be back.”

The Devil’s behavior seems reflected in what some human rights defense organizations were pointing out in their reports around the same time. “Constant threats are considered acts of torture (…)”, stated Johanna Ramírez, a lawyer and coordinator of the Victim Support Area at the Pasionist Social Service, an NGO that monitors the state of human rights in El Salvador. Despite the voices denouncing torture by the State, the government continues to evade ratifying the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment of the United Nations (UN).

Elías had to disappear from the map of Nazareth and forget the warmth of his family and the countryside-scented air of his home. He no longer complains about the darkness with which he had to arrive at Nazareth or the poor road condition. Elías went to rent loneliness: a tiny room in a certain city where he doesn’t talk to anyone but himself. He fears that the biblical devil embodied in a police officer will stalk him and finish him off. In self-protection, he lives a new life that separated him from his mother’s morning kiss and his full days off in his old hammock. Now, the days pass through the phone: video calls with those left behind. Pictures. A distorted I love you through the speaker. Elías’s life can be said to be on hold.

And there are hundreds of documented cases, like Elías, that involve the uprooting of hundreds of people because of the state of emergency. In the first 18 months of the state of emergency, from March 2022 to September 2023 alone, the José Simeón Cañas Central American University’s Human Rights Institute (UCA) registered 233 cases (some cases include more than one person) of forced internal displacement. The perpetrators were police officers and military personnel.

The Devil of Nazareth is blonde, people in the village say. They estimate he is about 40 years old. And they consider him belligerent and prone to violence and confrontations.

Until the end of November 2023, The Devil of Nazareth still had his official base in the rural area of Huizúcar, near the cemetery. GatoEncerrado made two phone calls to The Devil, one on September 15 and another on September 27, 2023, to ask him about his open case in the PNC Internal Affairs Unit.

During the September 15 call, he said phrases like “I don’t know anything about that” and “very strange, honestly.” When The Devil tired of hearing questions about his daily activities in Nazareth village and his relationship with the community, he decided to talk about his family: “I have four children, a wife… my family. If you see a police officer as an animal, no, we’re not like that, we have family. And if you’re going to tear me apart… well, with that, you’ll tear me apart… I hope you don’t…”

In that first conversation, he denied harassing anyone or threatening anyone’s freedom. He said he did not remember threatening anyone to create a false profile. Moreover, he claimed that he hadn’t even had a threatening argument with someone from the community.

On September 27, during the second call, he again denied everything, but his impatience flared up sooner:

“Good morning, Roberto. We want to talk to you again. We know that in Nazareth, you have threatened to create profiles of gang members without people having a previous criminal record.”

“Really weird, honestly… Those situations… The truth is that there are things that people… people… what can I say to you about this situation with people?”

“Well, we know that there is a pending case for aggravated theft with the Prosecutor’s Office. And it’s not the only open file against you…”

“I don’t know that I have any pending charges, as if I were a criminal. There are people who may feel bad about the situations, but those are things that happen. There are people who may not like the way we work.”

“The accusation has your full name and includes your ONI (a unique identification number that each police officer must wear visibly on their uniform as a guarantee of good behavior and so that citizens can identify and report a police officer in case of abuse, indiscipline, or violation of the law).”

“Uh-huh, yes, very strange. (…) Look, I answer your calls because… well, I don’t need to be taking calls because policemen don’t go around giving out information or talking about anything… if I wanted to, I’d tell you to go to hell…”

Officially, 7,000 people could not escape the Devils in the first 16 months of the state of emergency. On average, almost 15 people were unjustly detained by Devils like the one from Nazareth, who constantly lurk. Figures that President Bukele boasts about, oblivious to the suffering of Elías’s mother and the thousands of other mothers of other Elíses.

A year and a half after The Devil serving Bukele threatened Elías just 9 miles from downtown San Salvador, the president appeared in public with a broad smile. It was the night of February 4, 2024, and the president was addressing a crowd gathered in Plaza Gerardo Barrios, in downtown San Salvador, to celebrate the approval of a second term, prohibited by the Constitution, secured in rigged elections.

Thousands of people gathered in the capital’s center shout and chant “Bukele, Bukele, Bukele!” and celebrate every word he says. There is the man who has seemingly solved the security problem that gangs have been since the late 1990s. A problem, according to the government, is on the verge of being resolved after a bloody war that, like any war, causes collateral damage such as imprisoning thousands of innocent people, dozens of whom have died in prison and not a few with signs of torture or beatings attributable to police officers or prison guards. At least 200 people have died under these conditions in Bukele’s prisons.

On February 4, 2024, Bukele, who preaches that human rights are an obstacle to his plans, is about to conduct a kind of consultation amid the purest populism that he claims to defend: “Democracy is the power of the people,” he remarks, to the delight of his followers, who celebrate those words as if they were a divine revelation. The crowd is ecstatic, and Bukele knows how to lead them where he wants. “Some people who don’t even know El Salvador say that Salvadorans live oppressed and don’t want the state of emergency…” And the euphoric crowd of thousands of potential Elíses roars in favor of Bukele and more state of emergency.

Epilogue

Three months after GatoEncerrado went to the Zaragoza Prosecutor’s Office in La Libertad to ask why officer José Roberto Amaya Zelaya had not been presented to a judge for a complaint that had been in process for 15 months, the institution ordered his capture. On January 26, 2024, Elías recognized the police officer in front of a judge during the first hearing in which The Devil was accused of theft and limitation of free movement to the detriment of Elías. He is also accused of extortion and limitation of free movement against a second victim, not identified in this account. As of February 20, 2024, the officer was being held in the Conchalío, La Libertad cells while his trial continued.

Gato Encerrado: https://gatoencerrado.news/2024/02/21/el-diablo-viste-de-policia/

El Diablo viste de policía

El sol comenzaba a esconderse el viernes 15 de julio de 2022 cuando Elías volvía a su casa luego de 12 horas de trabajo en un restaurante de comida rápida en las afueras del Área Metropolitana de San Salvador. La motocicleta que había comenzado a pagar un par de meses antes iba rengueando por una calle rural que lo llevaba a un cantón a solo 8 kilómetros al sur de la capital salvadoreña. Elías zigzagueaba y alternaba acelerones con frenazos para esquivar los cráteres de aquellas ruinas de pavimento. El joven de 24 años se conducía con la tranquilidad de quien nada debe, pero poco después de pasar por debajo del arco que saluda “Bienvenidos a Nazareth” se inquietó cuando a un lado del camino distinguió una silueta que levantó la mano para ordenarle alto. Era El Diablo vestido de azul oscuro y le acompañaban otras dos siluetas que vestían de verde olivo.

Aquel trío estaba ahí oficialmente dedicado a buscar tatuajes, armas de fuego o un documento único de identidad (dui) que delatara un pasado pandilleril de aquellas personas a quienes retuviera. Extraoficialmente también cabía la posibilidad de que solo buscara llenar la cuota de capturas que el gobierno del presidente Nayib Bukele ha estado exigiendo a la Policía Nacional Civil desde cuando inició el régimen de excepción en marzo de 2022, sin importar si la persona a quien se detiene es pandillera o no. El Diablo y sus acompañantes tenían su retén en un territorio disputado históricamente por la Mara Salvatrucha y el Barrio 18 y, dada la intensa actividad de pandillas en la zona, aquel era quizás un buen punto donde intentar pescar algún “terrorista”.

La primera parte de la inspección policial terminó sin novedad: Elías no tenía tatuajes alusivos a pandillas y su número de dui no llevaba a ningún historial delictivo por el que detenerle. Todo parecía ir bien hasta que El Diablo comentó que le parecía sospechoso que uno de los dos celulares de Elías estuviera descargado. Ese fue todo el motivo por el que decidió que se lo decomisaría y le prometió devolverlo después de que lo revisara y constatara que el teléfono no contenía información incriminatoria. Elías no estuvo de acuerdo, pero sabía que en esos días abundaban los agentes arbitrarios que por menos que el reclamo de un celular podían enviar a prisión a cualquiera. Y aunque Elías se sintió robado, pensó que por lo menos podría continuar su camino a casa. Y eso hizo.

Al siguiente día, Elías denunció ante la Policía Nacional Civil a El Diablo por hurto agravado. No tenía cómo saber que acudir ante la institución responsable de prevenir y combatir el delito supondría para él no solo el fin de su tranquilidad, sino también su destierro. Porque El Diablo, furioso, llegaría un día después a anunciar a la madre de Elías su propósito de acosarles y amenazarles a tal punto que el joven no tendría alternativa: “Se va a tener que ir a la mierda de aquí”, sentenciaría.

El cantón Nazareth es casi invisible entre las colinas cubiertas de bosque de cafetal en el municipio de Huizúcar y tiene una riqueza hídrica que codician quienes levantan decenas de residenciales y centros comerciales en los municipios vecinos. En Nazareth no faltan el agua ni la energía eléctrica, pero conseguir señal de internet o de teléfono es poco menos que un milagro.

Al hacer una búsqueda en Google del “cantón Nazareth”, la información de los últimos diez años es mayormente sobre extorsiones, desapariciones, desplazamiento forzado, asesinatos y pandillas…

En la alcaldía de Huizúcar nadie sabe decir con certeza cuántas personas habitan el lugar. En palabras de los nazarenos, es un lugar que solo le importa a quienes viven ahí y que hoy, con el régimen de excepción, la amenaza a la vida de sus habitantes sólo cambió de bando: migró de las pandillas hacia los uniformados.

Elías es quizá el típico joven que porta injustamente el estigma del potencial pandillero. Y para los criterios de El Diablo, Elías no puede ser otra cosa que pandillero: tiene 24 años, con el agravante de que porta dos celulares. Y con un agravante más: uno de los celulares está descargado. Elías carece de tatuajes, de un talante violento o iracundo y de un perfil en la Policía Nacional Civil que lo identifique como pandillero o simpatizante de pandillas. Y ahora, dos días después del encuentro en la calle, Elías vuelve a escuchar la voz de El Diablo:

―Dígale que salga, si no, yo lo voy a tener bien taloneado y se va a tener que ir a la mierda de aquí.

La amenaza la recibe en su casa la madre de Elías la tarde del 17 de julio de 2022 de boca del agente José Roberto Amaya Zelaya, a quien algunos habitantes de la comunidad apodaron El Diablo porque lo consideran perverso y abusivo. La madre de Elías ha salido a tratar de contener aquel torrente violento vestido de policía y se para en el vano de la puerta de su casa, como si fuera una barricada de carne y huesos, desafiante, confiada en que la ley que aquel hombre debería cumplir y hacer cumplir está del lado de su hijo y de ella.

El agente reclama que Elías lo haya denunciado por haberse llevado arbitrariamente su teléfono celular. Y como la mujer resiste, El Diablo, pistola a la cintura, decide mostrarle el arma más poderosa que un agente policial inescrupuloso porta en estos días de régimen de excepción: si el joven no sale escribirá un perfil con información falsa para presentar a su hijo como pandillero y capturarle.

La amenaza

La comitiva que busca a Elías el 17 de julio es la misma con la que se halló el día del retén: El Diablo y dos soldados que se transportan en una todoterreno que ahora está aparcada en la calle. El Diablo detuvo la marcha del vehículo frente al sendero que lleva hasta la casa de Elías y caminó un par de metros entre piedras. Aunque los perros alertaron sobre la presencia desconocida, El Diablo se metió a la fuerza como si aquella propiedad le perteneciera o como si llevara orden judicial de allanamiento y se encaminó entre alambres de púas y tablones.

Con la alerta de los perros, quien salió a ver qué pasaba fue la madre de Elías y de inmediato comprendió lo que pasaba.

―Dígale a su hijo que salga -le insiste, y la mujer, que teme una captura arbitraria, le responde que no.

La madre de Elías refuerza la barricada humana con un sillón roto que alguna vez pensó para evitar el ingreso o salida de los perros. Ella sabe que su hijo denunció a un policía, y hoy es ese hombre garante del respeto de la ley quien viene a amenazarle. Como la amenaza de forzarlo a marcharse de Nazareth no da frutos, El Diablo, desafiado por la resistencia de la mujer, sube la apuesta:

―Si no sale le voy a sacar perfil y lo voy a meter preso junto con todo y el teléfono ―le advierte.

Así explica El Diablo aquella potestad que algunos policías creen tener en medio de la atmósfera de suspensión de derechos ciudadanos y de estimulación de abusos policiales generada bajo la sombra del régimen de excepción.

“Sacarle perfil” a un ciudadano significa montarle un expediente policial con información falsa que hable de la pandilla o de la organización criminal a la que pertenece para así justificar su captura. Elías está a una nada de que El Diablo le cree esa biografía falsa.

―El teléfono no se lo estoy robando, pero no se lo voy a dar mientras él no salga…

El policía no piensa en otra cosa que no sea en lograr que Elías salga de su casa y ahora intenta persuadirlo con el anzuelo de recuperar el celular. Pero tiene que salir a traerlo él mismo, en este lugar solitario donde no hay cerca personas que puedan ayudarle a él o a su madre.

Elías no saldrá. Sabe que salir significaría la cárcel y probablemente la muerte en prisión, pero aquel hombre uniformado es persistente. Elías no soporta la tensión y rompe en llanto oculto detrás de la puerta, recostado sobre el quicio.

Después de largos minutos de insistencia, El Diablo se resigna a que, por esta vez, su prepotencia no saldrá victoriosa, pero advierte con claridad que Elías no podrá vivir ahí nunca más.

―Yo sé que lo voy a volver a ver… o si no, que se vaya a la mierda de aquí…

El Diablo se dispone a marcharse cuando escucha a un Elías lloroso, quien ha tomado valor para desafiar aquella lógica perversa:

―No me puede llevar porque yo no he hecho nada.

El Diablo sabe que Elías tiene razón, pero le expone inmediatamente cómo funciona un mecanismo plagado de arbitrariedades que, probablemente, sea el mismo gracias al cual el gobierno de Nayib Bukele ha apresado a uno de cada 100 habitantes de El Salvador en esta cruzada antiterrorista que para febrero de 2024 ya dura casi dos años y que para agosto de 2023 ya admitía el encierro de al menos 7 mil personas inocentes.

―Si yo quiero, aunque no tenga perfil ahorita, yo lo meto preso, porque yo sé bien lo que hago.

Cuando dice que él sabe bien lo que hace, no está diciendo que hace lo correcto, sino lo que su capricho le ordena. Y añade unos detalles que sugieren que las piezas del sistema están diseñadas para que toda la ilegalidad funcione como una máquina eficiente:

―Yo hago un informe dirigido al jefe de la DIC (División de Investigación Criminal) y él rápido, en el instante, me apoya.

Esta especie de confesión fue demasiado para los oídos de Elías, porque ya para entonces se conocía un sinnúmero de denuncias ciudadanas de procedimientos arbitrarios de la PNC en nombre del régimen de excepción: un decreto legislativo modelado por el presidente Bukele que ha servido para amparar malos policías que usan a su antojo la ficha policial, que muchas veces no detalla pero sí señala la pertenencia de una persona a pandillas.

La creación de las fichas policiales está a cargo de Inteligencia Policial con base en el expediente delictivo de las personas sospechosas, pero en días de régimen de excepción comenzaron a abundar fichas basadas únicamente en la apariencia de las personas o en el estado de ánimo de los agentes. Algunas ni siquiera tienen fecha de creación. En todo caso, ahora la Fiscalía incluye entrevistas con los policías captores como prueba. Esos policías que, como El Diablo, pueden ser los artífices de fichas sin sustento.

Una gran parte del éxito del régimen de excepción descansa en esa metodología que le ha permitido a la Policía capturar a más de 75 mil personas acusadas, en su mayoría, de ese delito llamado agrupaciones ilícitas. En agosto de 2023, el ministro de Seguridad, Gustavo Villatoro, reveló que hasta entonces 7 mil personas habían sido liberadas después de que el sistema concluyó que no había pruebas de vinculación con pandillas. Tácitamente el régimen admitió que tuvo encerradas durante meses a miles de personas inocentes acusadas de ser pandilleras. Si Elías no se hubiera resistido a las exigencias de El Diablo aquella tarde de julio de 2022, quizás no habría tenido la oportunidad de escoger el camino que al final tuvo que tomar: el exilio forzoso.

El dilema en que el régimen de excepción ha puesto a miles de personas acosadas por policías y militares es que están obligadas a elegir entre dos desgracias: o ir presas sin ningún tipo de garantía legal o irse. Es decir, arriesgarse a terminar olvidadas y morir en las mazmorras de Bukele, o simplemente desarraigarse.

Como han constatado tanto la prensa como organismos de derechos humanos, la sentencia contra una persona inocente que se tropieza con el régimen de excepción empieza en la calle, cuando se enfrenta al “juez de la calle”, el policía. Un apelativo acuñado por el director de la institución, Mauricio Arriaza Chicas, en febrero de 2023, para referirse a los agentes policiales.

Arriaza es un jefe policial cuyo trabajo no necesariamente se ha caracterizado porque ofrezca garantías de respeto a los derechos humanos o de imprimir corrección en el desempeño de las unidades bajo su mando. Por ejemplo, entre 2016 y 2018 estuvo bajo escrutinio como jefe de las Áreas Especializadas de la Policía, cuando varios de sus subordinados fueron señalados de integrar grupos de exterminio. Uno de los agentes del Grupo de Reacción Policial asesinó a una compañera agente, Carla Ayala, y varios de sus compañeros fueron procesados porque no hicieron nada por evitar el feminicidio o por detener al feminicida, o porque le facilitaron la huida.

Hasta el 31 de octubre de 2023, la organización defensora de derechos humanos Cristosal documentaba 5,495 abusos policiales desde marzo de 2022, cuando inició el régimen de excepción. Más de la mitad de esos casos eran capturas arbitrarias.

El 14 de septiembre de 2023, un equipo de GatoEncerrado acudió al puesto policial de Huizúcar, al sur de San Salvador, para intentar conversar con el agente José Roberto Amaya Zelaya. Atendió el jefe del puesto. Cuando se le explicó el motivo de la visita, preguntó si esos “problemas en Nazareth” sobre los que este periódico quería cuestionar al agente policial se relacionaban con la ocasión en que El Diablo había estado preso. Una información nueva para el equipo periodístico, aunque el jefe no brindó detalles de ese caso. Luego explicó que ese día José Roberto Amaya Zelaya estaba en día libre, pero sí facilitó que el equipo pudiera comunicarse con el agente, por si este accedía a dar declaraciones.

A raíz del caso del celular de Elías, El Diablo tiene una mancha en su expediente, según consta en la denuncia que está en la Unidad de Asuntos Internos de la Policía.

La Unidad de Asuntos Internos pertenece a la Secretaría de Responsabilidad Profesional de la Dirección General de la Policía. De esta secretaría dependen también las unidades de Investigación Disciplinaria, Control y Derechos Humanos. Si un policía ha cometido una falta disciplinaria su caso es remitido a la Unidad de Investigación Disciplinaria, pero si el caso es de índole penal le corresponde investigarlo a la Unidad de Asuntos Internos en coordinación con la Fiscalía.

Una fuente de la PNC aseguró a este medio que este caso llegó a la Fiscalía. GatoEncerrado preguntó a la oficina de la Fiscalía en Zaragoza por el caso de El Diablo, donde respondieron que no podían dar información. Lo que sí mencionaron es que el agente tiene ya varias denuncias por situaciones similares a la que denunció Elías.

En un intento por obtener información sobre el avance del caso contra El Diablo, GatoEncerrado hizo una visita y dos llamadas telefónicas al jefe de la Unidad de Patrimonio de la Fiscalía de La Libertad Sur, en Zaragoza, Ricardo Emilio Cruz, pero las tres gestiones fueron infructuosas.

Y hasta finales de 2023, El Diablo continuaba trabajando e inquietando a la comunidad de Nazareth.

El Diablo vuelve

Transcurridos tres meses desde cuando el agente José Roberto Amaya Zelaya irrumpió en la vivienda de Elías y su madre, su acoso y amenazas continuaban. El Diablo es persistente. A mediados de octubre volvía a amenazar, pero esa vez ya no a Elías.

—¿Ya vino tu hermano? —pregunta El Diablo a una joven mujer esta tarde del 15 de octubre de 2022.

El hermano por quien pregunta es Elías, y la mujer es Ana. Ana guarda silencio.

—¿No vas a hablar? Si no decís nada, a vos te vamos a llevar presa.

Ana se atreve a musitar una escueta respuesta.

—Aquí no está. La vez pasada usted le dijo que se fuera… y se fue.

Aquellas palabras que le cuentan del desplazamiento forzoso de Elías tal vez deberían bastar a El Diablo para celebrar su victoria. Pero no. Ni eso sacia su sed. Posiblemente lo que quiere que le diga es dónde exactamente se encuentra hoy el joven.

—¿Ah?… Entonces te vamos a llevar a vos. ¡Dame el dui!

Ana siente que un frío recorre su cuerpo y enmudece por unos segundos. El hombre armado le exige que le muestre su documento único de identidad y le anuncia que la capturará. Porque sí. Porque puede hacerlo.

Tres meses antes su hermano había elegido el exilio por sobre el riesgo cierto de la cárcel y ahora es ella quien sufre la amenaza. La historia se repite.

Ana no puede recordar ese día sin que la voz se le arrastre. Y cuando hace el relato de aquel encuentro, su hija, quien apenas ha comenzado a ir a la escuela, corre a esconderse porque le aterroriza.

Ana quería explicarle a El Diablo que la voz de Elías ya no se oía más en esa casa. Que no se asomaba ni a hurtadillas. Que si revisaba la casa constataría que solo quedaban de él su cama, un par de trapos y el recuerdo de cuando volvía en la noche, exhausto, después de sus extensas horas de trabajo. Ana quería decirle que Elías había huido. Que para salvaguardar su vida, su hermano había renunciado a todo lo que en realidad constituía su vida.

El Diablo finalmente deja de refunfuñar, pero no de amenazar. Le devuelve el dui y le dice: “Voy a volver”.

La conducta de El Diablo parece reflejada en lo que en esos mismos días estaban señalando en sus informes algunas organizaciones de defensa de los derechos humanos. “Las amenazas constantes son consideradas actos de tortura (…)”, exponía Johanna Ramírez, abogada y coordinadora del área de Atención a Víctimas del Servicio Social Pasionista, una oenegé que vigila el estado de los derechos humanos en El Salvador. A pesar de las voces que denuncian torturas de parte del Estado, el gobierno continúa evadiendo ratificar el Protocolo Facultativo de la Convención contra la Tortura y Otros Tratos o Penas Crueles, Inhumanos o Degradantes de Naciones Unidas (ONU).

Elías tuvo que borrarse del mapa de Nazareth y olvidarse de la calidez de su familia y del aire con olor a campo de su casa. Ya no se queja de la oscuridad con la que tenía que llegar a Nazareth ni de la calle en mal estado. Elías se fue a rentar la soledad: una minúscula habitación en cierta ciudad donde no habla con nadie más que con él mismo. Teme que aquel diablo bíblico encarnado en un agente policial lo aceche y lo acabe. Autoprotegiéndose vive una vida nueva que le separó del beso de su madre por las mañanas y de los días de descanso pleno en su vieja hamaca. Ahora los días pasan a través del teléfono: videollamadas con los que ha dejado atrás. Imágenes. Un te amo distorsionado por la bocina. De la vida de Elías se puede decir que todo ha quedado en suspenso.

Y hay centenares de casos documentados que, como sucedió a Elías, suponen el desarraigo de cientos de personas por causa del régimen de excepción. Solo el Instituto de Derechos Humanos de la Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas (UCA) registró 233 casos (algunos casos incluyen más de una persona) de desplazamiento forzado interno durante los primeros 18 meses de régimen de excepción, de marzo de 2022 a septiembre de 2023. Los verdugos fueron policías y militares.

El Diablo de Nazareth es chele, dicen en el cantón. Le calculan unos 40 años de edad. Y lo consideran un pendenciero y con predisposición a la violencia y a buscar bronca.

Hasta finales de noviembre de 2023, El Diablo de Nazareth aún tenía su base oficial en la zona rural de Huizúcar, cerca del cementerio. GatoEncerrado hizo a El Diablo dos llamadas telefónicas, una el 15 y otra el 27 de septiembre de 2023, para consultarle sobre su caso abierto en la unidad de Asuntos Internos de la PNC.

Durante la llamada del 15 de septiembre, de su boca fluyeron frases como “desconozco todo eso” y “bien raro, la verdad”. Cuando El Diablo se cansó de escuchar preguntas sobre lo que hace a diario en el cantón Nazareth y su relación con la comunidad, decidió hablar de su familia: “Yo tengo cuatro hijos, esposa… mi familia. Si ustedes ven a un policía como un animal, no, no somos así, tenemos familia. Y si me van a hacer leña… pues con eso me hacen leña… espero que no lo hagan…”

En esa primera conversación negó acosar a persona alguna ni amenazar la libertad de nadie. Dijo no recordar haber amenazado con crear un perfil falso de ningún poblador. Más aun: sostuvo que ni siquiera ha tenido una discusión amenazante con alguien de la comunidad.

El 27 de septiembre, durante la segunda llamada, volvió a negarlo todo, pero su impaciencia estalló más pronto:

—Buenos días, Roberto. Queremos conversar nuevamente con usted. Sabemos que en Nazareth usted ha amenazado con crear perfiles de pandilleros sin que las personas tengan un historial delictivo previo.

—Bien raro, la verdad… Esas situaciones… La verdad que allí son cosas que la gente… la gente… ¿qué le podría decir yo con esta situación de la gente?

—Bueno, sabemos que hay un caso por hurto agravado en manos de la Fiscalía. Y que no es el único expediente abierto en su contra…

—Yo desconozco que yo tenga así, pues, pendientes, como si yo fuera un delincuente. Hay gente que quizá se siente mal por las situaciones, pero son cosas que suceden. Hay gente que quizá no le gusta la forma de trabajar de uno.

—La denuncia tiene su nombre completo e incluye su ONI (un número de identificación que cada agente policial debe portar visible en su uniforme concebido como garantía de buena conducta y para que la ciudadanía pueda identificar y denunciar a un policía en caso de un abuso, de un acto indisciplinario o de violación a la ley).

—Ajá, sí, bien raro. (…) Mire, le respondo sus llamadas porque… bueno, yo no tendría que recibirle llamadas porque los policías no andan dando información ni platicando nada… si yo quisiera a la m (mierda) la mandaría…

Oficialmente, 7,000 personas no pudieron librarse de los diablos en los primeros 16 meses de régimen de excepción. En promedio casi 15 personas fueron detenidas injustamente por diablos como el de Nazareth, en constante acecho. Cifras para jactancia del presidente Bukele, ajeno al sufrimiento de la madre de Elías y de las miles de madres de otros Elías.

Un año y medio después de que El Diablo al servicio de Bukele llegara a amenazar a Elías a escasos 15 kilómetros del centro de San Salvador, el presidente aparece en público con una sonrisa amplia. Es la noche del 4 de febrero de 2024, y el presidente se dirige a una multitud reunida en la Plaza Gerardo Barrios, del centro de San Salvador, para celebrar lo que en unas elecciones amañadas se cerró con una votación favorable para que desempeñe un segundo quinquenio prohibido por la Constitución.

Las miles de personas congregadas en el centro capitalino gritan y corean “¡Bukele, Bukele, Bukele!” y le celebran cada frase. Ahí está el hombre que les ha resuelto, en apariencia, el problema de inseguridad que han sido las pandillas desde finales de los años 90. Un problema que, según el gobierno, está a las puertas de resolverse tras una guerra sangrienta que, como toda guerra, provoca daños colaterales como encarcelar a miles de personas inocentes, decenas de las cuales han muerto en prisión y no pocas con señales de haber sufrido golpizas o torturas atribuibles a agentes policiales o a custodios de centros penales. Al menos 200 personas han muerto bajo estas condiciones en las cárceles de Bukele.

Este 4 de febrero de 2024, Bukele, quien predica que los derechos humanos son un estorbo para sus planes, está por hacer una especie de consulta en medio del más auténtico populismo que él dice defender: “Democracia es el poder del pueblo”, comenta, para deleite de sus seguidores, que le celebran aquellas palabras como si se tratase de una revelación divina. La multitud ha entrado en éxtasis y Bukele sabe cómo llevarles a donde quiere. “Por ahí dicen algunos que ni siquiera conocen El Salvador que los salvadoreños viven oprimidos y que no quieren el régimen de excepción…” Y aquella multitud de miles de potenciales Elías ruge eufórica en favor de Bukele y de más régimen de excepción.

Epílogo

Tres meses después de que GatoEncerrado acudiera a la Fiscalía de Zaragoza, en La Libertad, para preguntar por qué al agente José Roberto Amaya Zelaya no había sido presentado ante un juez por una denuncia que llevaba 15 meses en proceso, la institución ordenó su captura. El 26 de enero de 2024, Elías reconoció al agente policial frente a un juez, en la primera audiencia en la que El Diablo fue acusado por los delitos de hurto y limitación a la libre circulación en perjuicio de Elías. Asimismo, está acusado de extorsión y limitación a la libre circulación en perjuicio de una segunda víctima, no identificada en este relato. Hasta el 20 de febrero de 2024 el agente se encontraba detenido en las bartolinas de Conchalío, La Libertad, mientras continuaba su proceso.

Gato Encerrado: https://gatoencerrado.news/2024/02/21/el-diablo-viste-de-policia/