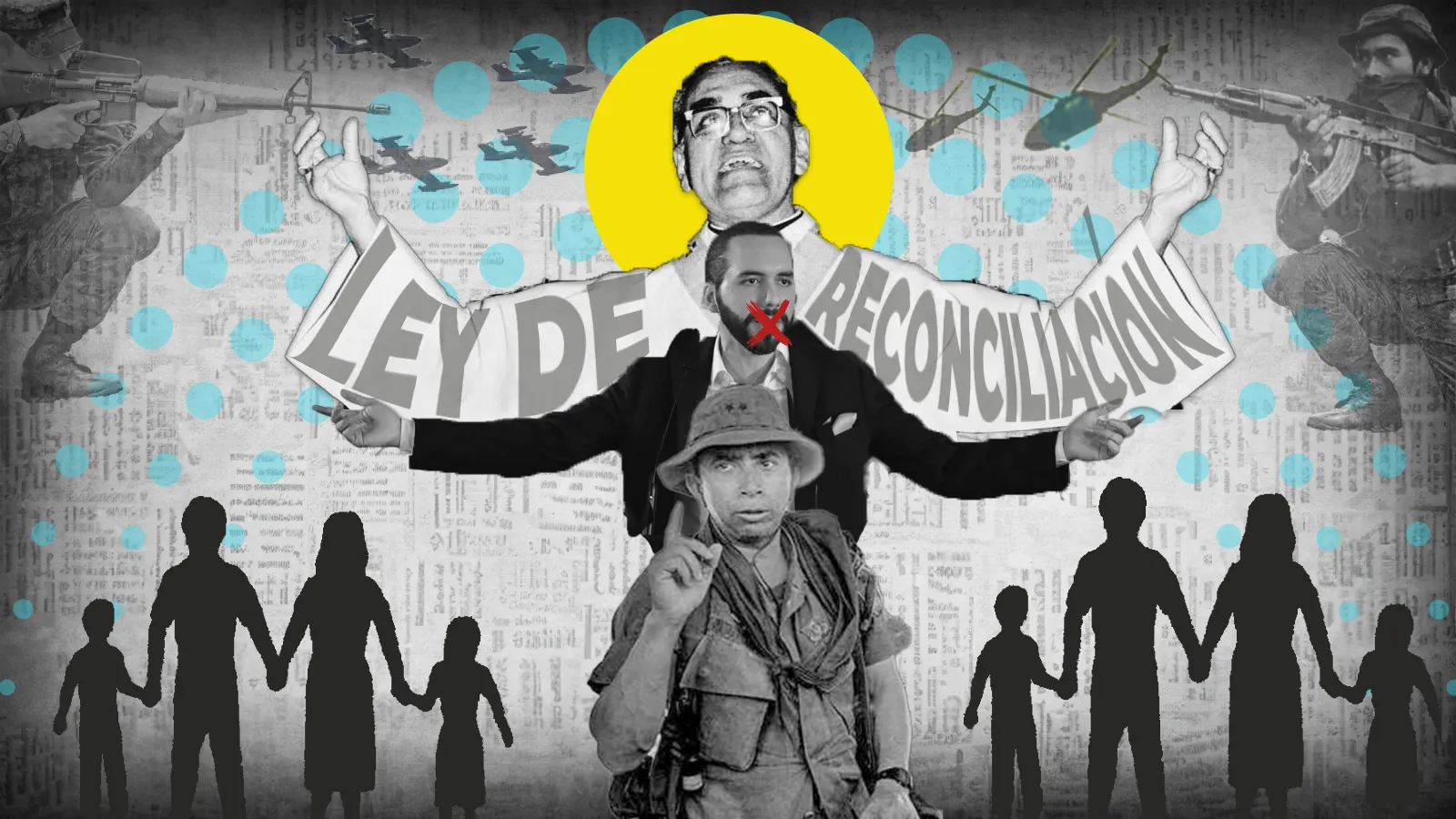

On February 26, 2020, the previous Legislative Assembly approved the Special Law on Transitional Justice, Reparation, and National Reconciliation. Two days later, President Nayib Bukele announced that he had vetoed it, arguing that it was “unconstitutional” and calling it “equally disgusting” as the Amnesty Law that guaranteed impunity for those who committed crimes against humanity and serious human rights violations during the armed conflict (1980-1992).

In this matter, Bukele has shown a chameleon-like behavior. At the beginning of his term, he opened the doors of the Presidential House to representatives of the victims of the El Mozote case, promising them “the reparation they had long requested.” Then, with indignation, he vetoed the reconciliation law approved by the previous legislature, considering it a cover-up for war criminals, and committed to pressuring the next legislature to pass a true transitional justice law. However, when his party Nuevas Ideas swept the legislative elections in 2021, his stance immediately changed. He remained silent and did not demand anything from his own party’s deputies, who could have easily passed such a law due to their majority.

After the ruling party took control of the Assembly, Deputy Rebeca Santos became the president of the Committee on Justice and Human Rights, where the transitional justice law should have been studied. However, the topic never made it to the agenda. Furthermore, the president did not regularly convene meetings; this year, she only called for nine meetings, none of which included the topic on the agenda. In fact, the committee abandoned the study of the transitional justice law since February 2022.

This abandonment of the topic also constitutes contempt for the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice (CSJ), which in 2016 declared that the Amnesty Law, approved in 1993, was unconstitutional and ordered the Legislative Assembly to correct its mistake and pass a transitional justice law. After extensions granted by the Chamber, the previous Assembly reached an agreement to approve the law that was vetoed by Bukele in 2020. After the veto, the study of a transitional justice law was briefly resumed by the current legislature but immediately abandoned in February 2022, without explanations.

Benjamín Cuéllar, human rights defender and founder of the organization Vidas Demandantes (VIDAS), pointed out that a possible explanation for the silence and delay in the transitional justice law is that Bukele’s priority lies in his own interests rather than seeking “justice and truth” for the victims of the armed conflict.

“The president has two matters of interest: one is to be in good standing with big capital, and two, to be in good standing with the Armed Forces as an institution,” Cuéllar told GatoEncerrado.

According to Cuéllar, Bukele’s efforts to please these sectors are not a coincidence but a strategic move: “Bukele wants to be in good standing with the Armed Forces because they will serve him to confront social protests that will inevitably arise, which is why he is arming them to the teeth and making them grow. He also wants to continue being in good standing with the big capital of this country, that is, the oligarchs, the families that dominate this country, many of whom financed what happened during the war,” he stated.

A Superficial Study That Was Abandoned

One of the first decisions made by the committees of the current legislature, including the Committee on Justice and Human Rights, was to archive all pending bills and initiatives inherited from the previous legislature. The ruling party deputies wanted to start from scratch, so they cleared the table, claiming that everything done before was flawed or represented the vision of corrupt parties that dominated the legislative power. Among the discarded bills and files were some proposals that organizations and representatives of the victims of the armed conflict had submitted for the discussion of a transitional justice law.

For the organizations, the decision to indiscriminately archive the law proposals was a disrespect to the work they had done previously. However, they prepared a new proposal and on October 21, 2021, they submitted it to Claudia Ortiz, a deputy from the Vamos party, to initiate the law as a member of the Committee on Justice and Human Rights.

“What these people are asking for is just, they are victims of rights violations and were not necessarily combatants,” said Deputy Ortiz in October 2021.

Irene Gómez, from Cristosal, explained at that time that the proposed law they presented in support of the victims’ representatives was the result of general assemblies with the affected individuals, “so it contains the four elements in favor of the victims” demanded by the ruling of the Constitutional Chamber issued in 2016, which are reparations, victim registry, the organizational system that needs to be developed, and truth trials with international standards.

That was not the only transitional justice bill received by the deputies of the current legislature. On February 14, 2022, the former Human Rights Ombudsman (PDDH), Apolonio Tobar, presented a bill called the “Transitional Justice Law.” According to the former official, this bill was designed after a consultation conducted by the PDDH in 2020, which collected the “sentiments and thoughts” of families and victims of the armed conflict. However, some organizations claimed to be unaware of this proposal and stated that they were never consulted.

A week later, on February 21, 2022, the committee scheduled the study of the transitional justice law for the last time. On that date, they received representatives from the Association for Human Rights “Tutela Legal Dra. María Julia Hernández,” Adriana Mira, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Eduardo García, Director of the Pro-Búsqueda Association, who presented contributions for the formulation of the law. That meeting had the same purpose as the previous ones related to the topic: they were scheduled to receive officials and representatives of the victims.

In summary, the only times the topic was scheduled in the committee was to receive a series of officials and representatives of the victims. There was never an exhaustive study of the proposals and inputs they received to amend what the previous legislature had done. Then, the topic was simply abandoned. Without explanations.

Two weeks after the last meeting where the topic was scheduled, on March 20, 2023, the Mesa against Impunity in El Salvador (MECIES) and the Commission on Work in Human Rights Pro-Historical Memory presented a letter to the Legislative Assembly addressed to Deputy Rebeca Santos, reminding her that the transitional justice law is pending and requested her to consider the proposal they submitted on October 7, 2021. They also requested to be received by the committee to expand on their proposal, but the committee has not called them yet.

GatoEncerrado requested an explanation from Deputy Santos, through her communication team, regarding why the topic was abandoned without explanations and why she has not followed the “roadmap” she set for herself to pass the law, but there has been no response as of the time of this note’s closure.

In September 2021, Santos explained in the committee that she would follow six phases to achieve the approval of the law, and these would be her roadmap: studying the ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) and the presidential veto, creating an interinstitutional working group, structuring the law, and then concluding with the discussion and issuance of the initiative’s report to submit it for approval by the plenary.

The IACHR ruling Santos referred to was issued on May 28, 2019, ordering the Assembly to suspend the processing of the “Special Law on Transitional and Restorative Justice for National Reconciliation.” However, the previous Assembly ignored this and, against the ruling, approved the reconciliation law on February 26, 2020. That law was the one vetoed by Bukele.

David Morales, the legal head of Transitional Justice at Cristosal, explained on May 25 of this year, during an activity to collect testimonies from war victims to preserve “Historical Memory,” that in El Salvador, “state policies” have prevailed under the current and previous governments, promoting forgetfulness and denial of human rights violations, and above all, seeking “the construction of a system of impunity that does not allow full state recognition of the facts or reparation for the victims.”

Members of the Commission on Work in Human Rights Pro-Historical Memory of El Salvador even denounced that the Bukele government proposes mechanisms and actions that lead El Salvador back to the “disastrous and dark” past of the armed conflict, such as the state of exception, whose validity is extended month by month by ruling party deputies and their allies since it came into effect on March 27, 2022.

According to the members of the Commission on Work in Human Rights Pro-Historical Memory, the government continues to deny the right to truth and justice to the victims of the armed conflict, contradicting its own discourse when Bukele was campaigning to win the presidency.

“In his campaign, the president said that this was one of the central points, and until now, he has blatantly denied it. Concrete cases of this are refusing to open the military files. The most serious thing is the persecution of social leaders, the persecution of journalists. These are not characteristics of a democratic regime, but rather of an authoritarian regime,” said Vicente Cuchillas, a member of the Commission on Work in Human Rights Pro-Historical Memory.

Faced with the unexplained delay in studying and approving the law, Deputy Ortiz has stated that some victims have already died waiting for justice, and some perpetrators have also died in impunity.

“What has happened is a scandalous silence, unfulfilled promises, excuses, and it is evident that the Committee on Justice and Human Rights either does not want to do the work or is not given permission because they publicly committed to the victims. The victims are dying without finding justice, and the perpetrators are also dying without facing justice. Therefore, it seems that we are still in the same situation as in the past: perpetuating impunity, protecting the spurious interests that led to these serious human rights violations. In the long run, impunity in our country is becoming even more systematic, even more structural, and the issue is not being directly addressed,” Ortiz argued.

The deputy has also criticized that the current legislature, dominated by the ruling party, is behaving like previous Assemblies that left behind a legacy of impunity for war criminals.

Defender Benjamín Cuéllar added that in the face of the abandonment of the issue and the disregard for the victims by the ruling party, organizations will wait for the results of the 2024 elections to see how the next legislature is composed and decide if there is a possibility of designing a new strategy that responds to the victims of the armed conflict.

The 1993 Amnesty and the 2020 Reconciliation: Two Laws Guaranteeing Impunity

When the previous Legislative Assembly approved the reconciliation law with the votes of the right-wing parties Arena, PCN, and PDC, organizations and victims’ representatives argued that it was a “new amnesty” and that it was “shielding” war criminals.

In the face of the approval of that law, Eduardo García from the Pro-Búsqueda Association told GatoEncerrado at that time that the Assembly had allowed “denial of justice, constitutional principles, guarantees for victims, and had made an effort to exchange penalties and escape the condemnation of those responsible for grave atrocities.”

Bukele, on the other hand, argued that he vetoed that reconciliation law because it did not include measures for reparation and did not consider the families of the victims, so it also did not comply with the mandate of the previous Constitutional Chamber to design a new Transitional Justice Law to replace the General Amnesty Law for the Consolidation of Peace, which had been in effect since 1993.

The 1993 Amnesty Law prohibited the investigation of crimes and human rights violations committed by the Army and the former FMLN guerrilla. For that reason, the Constitutional Chamber explained in its 2016 ruling that crimes against humanity do not prescribe and that a transitional justice law is necessary to achieve comprehensive reparation for the victims.

“The amnesty is contrary to the right of access to justice, to judicial protection of fundamental rights, and to the right to comprehensive reparation for the victims of crimes against humanity and war crimes constituting serious violations of International Humanitarian Law,” the Chamber stated at that time.

Two years after the ruling, the previous Legislative Assembly formed a special committee in June 2018 to study a proposal initially promoted by the parties Arena, PDC, PCN, and the FMLN, although the latter did not vote in favor or abstain from voting on the final document that became law. They simply did not participate in the vote.

Two days before the right-wing deputies endorsed the “Special Law on Transitional Justice, Reparation, and National Reconciliation,” organizations such as the Mesa against Impunity in El Salvador, the Gestor Group for a Reparation Law, and the Commission on Work Pro-Historical Memory issued a statement rejecting the new “Reconciliation Law” that was about to be approved.

“It has been clear that the fundamental objective of the deputies throughout this process has been to formulate a Law of Impunity: that those responsible for war crimes do not receive prison sentences and that they are not affected in their assets,” they expressed in their statement.

Representatives of the organizations stated that the law sought to ensure that any perpetrator convicted of war atrocities would evade imprisonment, would not be affected in their assets under the concept of civil liability, and that their sentence would be reduced to unacceptable minimums for justice in the face of crimes against humanity.

According to the law approved in 2020 by the Assembly, those who confessed their war crimes, apologized, and cooperated with justice could have access to a reduction in their prison sentence. Additionally, judges could impose lesser or commuted sentences based on the “health, age, or similar” circumstances of the perpetrator.

The victims and representatives of human rights organizations indicated that the law approved in 2020 was offensive because it was born in an ad hoc committee composed of deputies linked to the crimes committed during the war and who had obstructed justice in the past, such as former PDC deputy Rodolfo Parker.

Former Deputy Parker is accused by the Truth Commission of obstructing justice in the case of the massacre of the Jesuit priests: Ignacio Ellacuría, who was the rector of the Central American University “José Simeón Cañas” (UCA); as well as the Spanish priests Ignacio Martín Baró, who served as the vice-rector of the UCA, Segundo Montes Mozo, Amando López Quintana, and Juan Ramón Moreno Pardo; in addition to the Salvadoran Jesuit priest Joaquín López y López, and two of his collaborators, Julia Elba Ramos and her daughter Celina Mariceth Ramos, perpetrated on November 16, 1989.

The rest of the members of the ad hoc committee were: General Mauricio Vargas, former Arena deputy and defender of Lieutenant Domingo Monterrosa, the main perpetrator in the El Mozote massacre; Colonel Antonio Almendáriz, former PCN deputy, also mentioned in the Truth Commission’s report; and Nidia Díaz, former guerrilla commander, peace negotiator, and former FMLN deputy. Juan Carlos Mendoza, currently a deputy for Gana, was also part of the committee.

Bukele also refused to collaborate with transitional justice

Part of the elements to guarantee comprehensive reparation for the victims, as ordered by the Chamber, is access to the truth of what happened. In that sense, Bukele, as the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces, had the opportunity to collaborate with transitional justice, but he did not. He refused to order the opening of military archives to establish responsibilities in the El Mozote massacre. He was also chameleon-like in this matter. He first said he would declassify all the files, “from A to Z,” but then changed his mind and argued that he could not open them due to national security reasons.

Gato Encerrado (Interactive timeline at source): https://gatoencerrado.news/2023/12/12/la-asamblea-de-bukele-tambien-abandono-a-las-victimas-del-conflicto/

La Asamblea de Bukele también abandonó a las víctimas del conflicto armado

El 26 de febrero de 2020, la anterior Asamblea Legislativa aprobó la Ley Especial de Justicia Transicional, Reparación y Reconciliación Nacional. Dos días después, el presidente Nayib Bukele anunció que la había vetado bajo el argumento de que era “inconstitucional” y la calificó de ser “igual de asquerosa” que la Ley de Amnistía que garantizaba impunidad a quienes cometieron delitos de lesa humanidad y graves violaciones a los derechos humanos durante el conflicto armado (1980-1992).

En este asunto, Bukele se ha mostrado camaleónico. Al inicio de su mandato, abrió las puertas de Casa Presidencial a los representantes de las víctimas del caso El Mozote, prometiéndoles “la reparación que tanto pidieron”. Luego, con indignación, vetó la ley de reconciliación que aprobó la legislatura anterior, por considerar que encubría a los criminales de guerra; y se comprometió a presionar a la siguiente legislatura para aprobar una verdadera ley de justicia transicional. Sin embargo, cuando su partido Nuevas Ideas arrasó en las elecciones legislativas de 2021, su postura cambió de inmediato. Guardó silencio y no exigió nada a sus diputados oficialistas, quienes fácilmente podrían haber aprobado una ley de este tipo por ser mayoría.

Luego de que el oficialismo asumió el control de la Asamblea, la diputada Rebeca Santos se convirtió en la presidenta de la Comisión de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, donde la ley de justicia transicional debería ser estudiada. Sin embargo, el tema ni siquiera llega a la agenda. Es más, la presidenta tampoco convoca a reuniones con regularidad; este año solamente convocó a nueve. En ninguna de esas convocatorias incluyó el tema en la agenda. De hecho, la comisión abandonó el estudio de la ley de justicia transicional desde febrero del 2022.

Ese abandono del tema también significa desacato (desobediencia) a la Sala de lo Constitucional de la Corte Suprema de Justicia (CSJ), que en 2016 declaró que la Ley de Amnistía, aprobada en 1993, era inconstitucional y ordenó que la Asamblea Legislativa enmendara su error y aprobara una ley de justicia transicional. Luego de prórrogas concedidas por la Sala, la Asamblea anterior logró un acuerdo para aprobar la ley que fue vetada por Bukele en 2020. Después del veto, el estudio de una ley de justicia transicional fue retomado brevemente por la actual legislatura, pero inmediatamente abandonado en febrero de 2022, sin explicaciones.

Benjamín Cuéllar, defensor de derechos humanos y fundador de la organización Vidas Demandantes (VIDAS), señaló que una posible explicación al silencio y al retraso de la ley de justicia transicional es que la prioridad de Bukele son sus propios intereses y no procurar “justicia y verdad” a las víctimas del conflicto armado.

“El presidente tiene dos asuntos que le interesan: uno es estar bien con los grandes capitales; y dos, estar bien con la Fuerza Armada como institución”, aseguró Cuéllar a GatoEncerrado.

De acuerdo con Cuéllar, que Bukele busque congraciarse con estos sectores no es una coincidencia, sino estratégico: “Bukele quiere quedar bien con la Fuerza Armada porque es la que le va a servir para enfrentar la protesta social que va a venir tarde o temprano, por eso la está armando hasta los dientes y la está haciendo crecer; y quiere seguir estando bien con los grandes capitales de este país, es decir, los grande oligarcas, las familias que dominan este país y muchos de ellos fueron quienes financiaron lo ocurrido durante la guerra”, afirmó.

Un estudio superficial que quedó abandonado

Una de las primeras decisiones que tomaron las comisiones de la actual legislatura, incluyendo la Comisión de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, fue la de enviar al archivo todos los expedientes en estudio e iniciativas de ley que heredaron de la legislatura anterior. Los diputados del oficialismo querían iniciar de cero y por eso hicieron un barrido de todo lo que les quedó en la mesa, bajo excusa de que todo lo anterior estaba mal hecho o representaba la visión de los partidos corruptos que dominaban el poder legislativo. Entre los proyectos de ley y expedientes que desecharon estaban algunas propuestas que organizaciones y representantes de víctimas del conflicto armado habían presentado para la discusión de una ley de justicia transicional.

Para las organizaciones, la decisión de archivar sin discriminación las propuestas de ley fue un irrespeto al trabajo que habían hecho anteriormente. Sin embargo, prepararon una nueva propuesta y el 21 de octubre de 2021 la entregaron a la diputada del partido Vamos, Claudia Ortiz, para que le diera iniciativa de ley como integrante de la Comisión de Justicia y Derechos Humanos.

“Lo que pide esta gente es justo, son víctimas de violaciones a sus derechos y no fueron necesariamente combatientes”, señaló la diputada Ortiz en octubre de 2021.

Irene Gómez, de Cristosal, explicó en ese entonces que el proyecto de ley que presentaron en acompañamiento a los representantes de las víctimas fue el resultado de asambleas generales con los afectados, “por lo que contiene los cuatro elementos a favor de las víctimas” que exige el fallo de la Sala de lo Constitucional emitido en 2016, los cuales son el fondo de reparaciones, el registro de víctimas, el sistema de organizaciones que debe trabajarse y juicios de la verdad con estándares internacionales.

Esa no fue la única iniciativa de ley de justicia transicional que recibieron los diputados de la actual legislatura. El 14 de febrero de 2022, el exprocurador para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos (PDDH), Apolonio Tobar, presentó una propuesta de ley llamada “Ley de Justicia Transicional”. Según explicó el exfuncionario, ese proyecto de ley fue diseñado tras una consulta, realizada por la PDDH en 2020, que recogió el “sentir y pensar” de las familias y las víctimas del conflicto armado. Algunas organizaciones, sin embargo, dijeron desconocer esa propuesta y que nunca fueron consultados.

Una semana después, el 21 de febrero de 2022, la comisión agendó por última vez el estudio de la ley de justicia transicional. En esa fecha recibieron a representantes de la Asociación de Derechos Humanos “Tutela Legal Dra. María Julia Hernández”; a Adriana Mira, viceministra de Relaciones Exteriores; y a Eduardo García, director de la Asociación Pro-Búsqueda, quien presentó aportes para la formulación de la ley. Esa reunión tuvo el mismo propósito que las anteriores que están relacionadas con el tema: se agendaron para recibir a funcionarios y a representantes de las víctimas.

En resumen, las únicas veces cuando el tema se agendó en la comisión fue para recibir una serie de funcionarios y a representantes de víctimas. Nunca se hizo un estudio exhaustivo de las propuestas e insumos que recibieron para enmendar lo que la legislatura anterior había hecho. Luego, el tema simplemente fue abandonado. Así, sin explicaciones.

Dos semanas después de la última reunión en la que se agendó el tema, la presidenta de la comisión, Rebeca Santos, aseguró en su cuenta de X que no descansaría hasta aprobar la ley de justicia transicional.

Unos meses después del abandono del tema, el 7 de octubre de 2022, la diputada Ortiz expresó ante los medios de comunicación que la Asamblea estaba haciendo una “dilación”: “Esas promesas de que vamos a entrarle al tema de las víctimas y de que vamos a trabajar por la justicia está cayendo en saco roto”, criticó.

Para Benjamín Cuéllar, lo que hizo la Comisión de Justicia y Derechos Humanos fue un “espectáculo” y nunca procuró aprobar una ley que lograra satisfacer las necesidades de las víctimas. Muestra de eso, según Cuéllar, es que antes de escuchar a las víctimas y a sus representantes, la comisión decidió escuchar a los exmiembros de la guerrilla devenidos en aduladores del bukelismo, Dagoberto Gutiérrez y Giovanni Galeas.

Tras meses de silencio y abandono del tema, el 20 de marzo de 2023, la Mesa contra la Impunidad en El Salvador (MECIES) y la Comisión de Trabajo en Derechos Humanos Pro-Memoria Histórica, presentaron una carta ante la Asamblea Legislativa dirigida a la diputada Rebeca Santos, recordando que la ley de justicia transicional está pendiente y pidieron que considere la propuesta que llevaron el pasado 7 de octubre de 2021. Además, solicitaron ser recibidos en el seno de la comisión para ampliar su propuesta, pero esa instancia sigue sin llamarlos.

GatoEncerrado pidió a la diputada Santos, a través de su equipo de comunicaciones, una explicación de por qué el tema fue abandonado sin explicaciones y por qué no ha seguido la “hoja de ruta” que se propuso a sí misma para aprobar la ley, pero hasta el cierre de esta nota tampoco hubo respuesta.

En septiembre de 2021, Santos explicó en la comisión que seguiría seis fases para lograr la aprobación de la ley y que las mismas serían su hoja de ruta: el estudio de la sentencia de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos humanos (Corte IDH) y el estudio del veto presidencial, la creación de una mesa interinstitucional, la estructuración de la ley, para luego terminar con la discusión y emisión del dictamen de la iniciativa para pasarla a aprobación del pleno.

La sentencia de la Corte IDH a la que Santos se refería es la que emitió el 28 de mayo de 2019 para que la Asamblea suspendiera el trámite de la “Ley Especial de Justicia Transicional y Restaurativa para la Reconciliación Nacional”; sin embargo, la Asamblea anterior hizo caso omiso y en contra de esa sentencia aprobó la ley de reconciliación el 26 de febrero de 2020. Esa ley es la que Bukele vetó.

David Morales, jefe jurídico de Justicia Transicional de Cristosal, explicó el 25 de mayo de este año, en una actividad de recopilación de testimonios de las víctimas de la guerra para conservar la “Memoria Histórica”, que en El Salvador han predominado “políticas de Estado” desde el gobierno actual y los anteriores, en donde se ha impulsado el olvido y el negacionismo de violaciones a derechos humanos, y sobre todo se ha procurado “la construcción de un sistema de impunidad que no permite el reconocimiento pleno estatal de los hechos ni la reparación a las víctimas”.

Los miembros de la Comisión de Trabajo en Derechos Humanos Pro Memoria Histórica de El Salvador denunciaron, incluso, que el Gobierno de Bukele plantea mecanismos y acciones que llevan a El Salvador al pasado “nefasto y oscuro” del conflicto armado; por ejemplo, el régimen de excepción, cuya vigencia es prorrogada mes a mes por los diputados oficialistas y sus aliados, desde que entró en vigor el 27 de marzo de 2022.

Para los miembros de la Comisión de Trabajo en Derechos Humanos Pro Memoria Histórica, el gobierno continúa negando el derecho a la verdad y justicia a las víctimas del conflicto armado, contradiciendo su mismo discurso cuando Bukele estaba en campaña electoral para ganar la presidencia.

“El presidente, en su campaña, dijo que esto era uno de los puntos centrales y hasta ahora lo ha negado descaradamente. Casos concretos de eso es negarse a abrir los expedientes de la Fuerza Armada. Lo más delicado es la persecución de los líderes sociales, la persecución de los periodistas, eso no es una característica de un régimen democrático, sino propias de un régimen autoritario”, señaló Vicente Cuchillas, integrante de la Comisión de Trabajo en Derechos Humanos Pro-Memoria Histórica.

Ante el retraso sin explicaciones para el estudio y aprobación de la ley, la diputada Ortiz ha señalado que algunas víctimas ya fallecieron esperando justicia y también algunos victimarios murieron en la impunidad.

“Lo que ha habido es un escandaloso silencio, promesas incumplidas, excusas y es evidente que la Comisión de Justicia y Derechos Humanos o no quiere hacer el trabajo o no le dan permiso, porque se comprometieron públicamente con las víctimas; las víctimas están falleciendo, están fallecido sin encontrar justicia y los victimarios también están falleciendo sin enfrentar la justicia; por lo tanto, tal parece que seguimos en la misma situación que existía en el pasado: perpetuar la impunidad, de proteger los intereses espurios que propiciaron esos actos de graves violaciones a los derechos humanos y lo que está sucediendo en el largo plazo es que la impunidad en nuestro país se está haciendo aún más sistemática, aún más estructural y no se quiere abordar el tema de una forma directa”, alegó Ortiz.

La diputada también ha criticado que la actual legislatura, dominada por el oficialismo, está comportándose como las anteriores Asambleas que dejaron como legado la impunidad de los criminales de guerra.

El defensor Benjamín Cuéllar agregó que ante el abandono del tema y el desprecio hacia las víctimas de parte del oficialismo, las organizaciones van a esperar los resultados de las elecciones de 2024 para observar cómo queda conformada la siguiente legislatura y decidir si existe la factibilidad de diseñar una nueva estrategia que responda a las víctimas del conflicto armado.

La amnistía de 1993 y la reconciliación de 2020: dos leyes que garantizaban impunidad

Cuando la anterior Asamblea Legislativa aprobó la ley de reconciliación, con los votos de los partidos de derecha Arena, PCN y PDC, las organizaciones y representantes de las víctimas aseguraron que era “una nueva amnistía” y que se estaba “blindando” a los criminales de guerra.

Ante la aprobación de esa ley, Eduardo García, de la Asociación Pro-Búsqueda, dijo en ese entonces a GatoEncerrado que la Asamblea se había prestado para “negar la justicia, principios constitucionales, garantías a las víctimas, y se había esforzado en permutar penas y en zafar de la condena a los victimarios de graves atrocidades”.

Bukele, por su lado, argumentó que vetó esa ley de reconciliación porque no contenía medidas de resarcimiento y no tomó en cuenta a las familias de las víctimas, por lo que tampoco dio cumplimiento al mandato de la anterior Sala de lo Constitucional de diseñar una nueva Ley de Justicia Transicional para sustituir la Ley de Amnistía General para la Consolidación de la Paz, que estaba en vigor desde 1993.

La Ley de Amnistía de 1993 prohibía investigar crímenes y violaciones a los derechos humanos cometidos por el Ejército y la exguerrilla del FMLN. Por esa razón, la Sala de lo Constitucional explicó en su fallo de 2016 que los crímenes de lesa humanidad no prescriben y que es necesario tener una ley de justicia transicional para conseguir una reparación integral de las víctimas.

“La amnistía es contraria al derecho de acceso a la justicia, a la tutela judicial o protección de los derechos fundamentales y al derecho a la reparación integral de las víctimas de los crímenes de lesa humanidad y crímenes de guerra constitutivos de graves violaciones al Derecho Internacional Humanitario”, afirmó la Sala de ese entonces.

Dos años después del fallo, la anterior Asamblea Legislativa formó en junio de 2018 una comisión especial para estudiar una propuesta impulsada inicialmente por los partidos Arena, PDC, PCN y el FMLN, aunque éste último no votó a favor ni se abstuvo de votar por el documento final que se convirtió en ley. Simplemente se ausentó de la votación.

Dos días antes de que los diputados de los partidos de derecha avalaran la “Ley Especial de Justicia Transicional, Reparación y Reconciliación Nacional”, las organizaciones como la Mesa contra la Impunidad en El Salvador, el Grupo Gestor por una Ley de Reparaciones y la Comisión de Trabajo Pro-Memoria Histórica, emitieron un comunicado de rechazo a la nueva “Ley de Reconciliación” que estaba por aprobarse.

“Ha sido claro que el objetivo fundamental de los diputados en todo este proceso ha sido, sobre todo, formular una Ley de Impunidad: que los responsables de crímenes de guerra no tengan penas de prisión y que no se vean afectados en su patrimonio”, expresaron en su comunicado.

Representantes de las organizaciones señalaron que la ley buscaba garantizar que cualquier victimario condenado por las atrocidades de la guerra evadiera la pena de prisión, que no se viera afectado en su patrimonio bajo concepto de responsabilidad civil y que su pena se redujera a mínimos inaceptables para la justicia ante crímenes de lesa humanidad.

Según la ley aprobada en 2020 por la Asamblea, quienes confesaran sus crímenes de guerra, pidieran perdón y colaboraran con la justicia, podrían tener acceso a una reducción de la pena de cárcel. Además, la prisión podría ser menor o conmutada por los jueces en razón de “salud, edad o similares” del victimario.

Las víctimas y representantes de organizaciones de derechos humanos indicaron que esa ley aprobada en 2020 era ofensiva porque había nacido en una comisión ad hoc, integrada por diputados vinculados a los crímenes cometidos en la guerra y quienes en el pasado obstaculizaron la justicia, como el exdiputado del PDC, Rodolfo Parker.

El exdiputado Parker es señalado por la Comisión de la Verdad de obstruir la justicia en el caso de la masacre de los padres jesuitas: Ignacio Ellacuría, quien era rector de la Universidad Centroamericana “José Simeón Cañas” (UCA); así como los sacerdotes españoles, Ignacio Martín Baró, que se desempeñaba como vicerrector de la UCA; Segundo Montes Mozo, Amando López Quintana y Juan Ramón Moreno Pardo; además del padre jesuita salvadoreño Joaquín López y López, y dos de sus colaboradoras, Julia Elba Ramos y su hija Celina Mariceth Ramos, perpetrado el 16 de noviembre de 1989.

El resto de miembros de la comisión ad hoc eran: el general Mauricio Vargas, exdiputado de Arena y defensor del teniente Domingo Monterrosa, principal implicado en la masacre de El Mozote; el coronel Antonio Almendáriz, exdiputado del PCN, también señalado en el Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad; y Nidia Díaz, excomandante de la guerrilla, negociadora de la paz y ex diputada del FMLN. También estaba Juan Carlos Mendoza, actualmente diputado de Gana.

Bukele también se negó a colaborar con la justicia transicional

Parte de los elementos para garantizar la reparación integral de las víctimas, como lo ordenó la Sala, es el acceso a la verdad de lo que ocurrió. En ese sentido, Bukele como comandante general de las Fuerzas Armadas tuvo la oportunidad de colaborar con la justicia transicional, pero no lo hizo. Se negó a ordenar que los archivos militares fueron abiertos para deducir responsabilidades en la masacre de El Mozote. En este tema también fue camaleónico. Primero dijo que iba a desclasificar todos los archivos, “de la A a la Z”, pero luego cambió de opinión y argumentó que por temas de seguridad nacional no podía abrirlos.

Gato Encerrado: https://gatoencerrado.news/2023/12/12/la-asamblea-de-bukele-tambien-abandono-a-las-victimas-del-conflicto/