Tomorrow at sunset I will drive to the gates of Bukele’s mega-prison and what will be, will be.

I am now in Tecoluca, in the department of San Vicente. I got up early in the morning to come to the municipality that has what the government of El Salvador has advertised as the largest prison in Latin America — in the world, some say — and I have decided not to return to San Salvador without at least trying to get close to it.

There are reasons for concern: Bukelismo is allergic to independent journalism; the area is full of soldiers and police; the country has been under a state of exception for more than a year and a half, which gives them a free pass for arbitrary detentions; and just yesterday I was held at gunpoint, restrained and threatened by a military officer when I wanted to photograph the gate of another prison, Zacatraz, as the Zacatecoluca Maximum Security Penal Center is known, located just eight kilometers from the mega-prison.

By Bukele’s mega-prison I mean CECOT, the acronym chosen for the Terrorism Confinement Center, perhaps the most emblematic work of President Nayib Armando Bukele Ortez’s first five-year term.

In El Salvador, members of Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), Barrio 18-Sureños, Barrio 18-Revolucionarios and other minor criminal structures have been considered terrorists since August 2015, following a ruling by the Constitutional Chamber.

But as I said: I will go to the prison with no invitation tomorrow at dusk, when the field reporting is finished. Before that, I will visit the urban center of Tecoluca and the surrounding communities, those that saw this huge work rise from one moment to the next -as they say-. Because they have talked non stop about the thousands and thousands of presumed emeeses (MSs, members of Mara Salvatrucha) and dieciocheros (members of Barrio 18) who are inside, but hardly anything about the neighbors: workers, students, cattle ranchers, old people, farmers….

-Ever since they opened it, that river stinks, but it really stinks… the water stinks… -Fátima Alvarenga, a young farmer from the Cantarrana hamlet, one of the most affected by the shit coming from the prison, told me; I used to wash my clothes there, but now, I do it in the house.

Pollution is what most worries the neighborhood of Bukele’s mega-prison. Between today and tomorrow I will hear of dead cows from drinking from once crystalline rivers, of agricultural production undervalued in the markets, and of an unbearable stench. I will also hear heartfelt complaints about militarization, about arbitrary detentions, about the prison not even having become a source of employment, about telephone signal failures, about….

And everyone I will interview, all without exception, will tell me that they believe the worst is yet to come. The number of prisoners incarcerated is around 12,000, barely 30% of the announced capacity.

***

Using the word “mega” to refer to this prison is not just another journalistic hyperbole. CECOT is truly gigantic. The prison covers 236,000 square meters, the equivalent of five times the size of Zocalo in Mexico City. It would take half an hour to walk around it… if you were allowed to get close to it.

According to the data that the Government releases at will, it has 37 watchtowers, 11 meter high perimeter walls, seven security rings, full housing for guards, also for guard dogs, a dozen workshops for painting, making desks, making clothes, etc., technology for virtual court hearings so that inmates do not leave the facilities, and its perimeter is guarded by 600 soldiers and 250 policemen.

Bukele’s mega-prison has eight wings for prisoners, completely independent of each other, and each of them is as large as the playing field of La Bombonera, the Boca Juniors stadium. Gigantic.

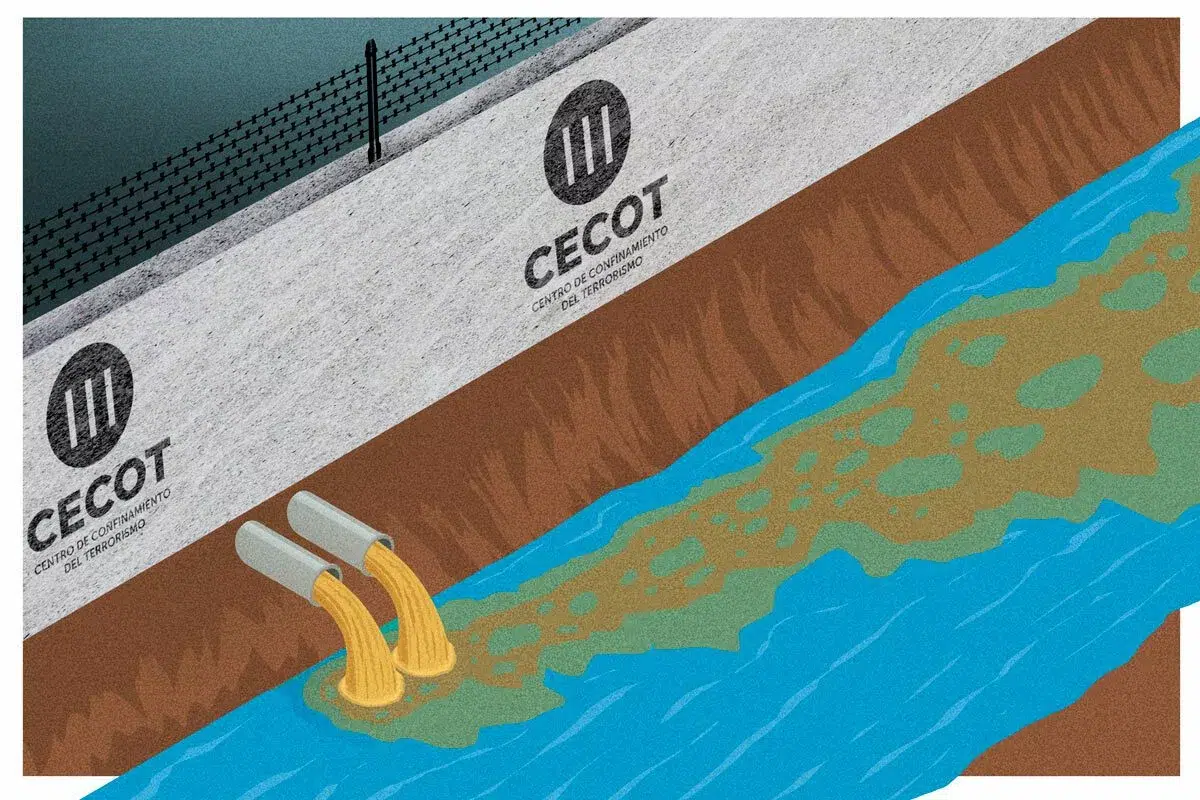

It was announced that CECOT would have its own sewage treatment plant but, if it works, it works terribly. Later you will understand.

The President of the Republic himself, Nayib Bukele, tweeted that it will hold “40,000 terrorists, who will be cut off from the outside world”, but, nine months after its inauguration, the number of inmates as of October 22 was 12,149.

But beyond the numbers, perhaps the most shocking fact is that in barely eight months it was built from nothing -from nothing-, on agricultural land. It was handled in secret, but a neighbor of Tecoluca contacted me on May 13, 2022 to tell me that there was heavy machinery in that area. Bukele announced his mega-prison to the world on June 21, and inaugurated it with great fanfare on January 31, 2023. It received its first 2,000 occupants on February 24.

Designing, allocating, building and equipping a project such as CECOT is a direct consequence of the state of exception that has been in effect since March 27, 2022, which, among other powers, allows the Bukele Administration to assign contracts by handpicking.

Another relevant fact is the location: El Perical de Tecoluca. “We decided to do it far from the cities,” Bukele himself proudly announced. The chosen land was located 70 kilometers from the capital, of infinite fertility, wedged between the Chinchontepec volcano and the Pacific Ocean; a territory with countless rivers, streams and creeks, an area of water recharge.

Regarding its distance from the cities, it is true that CECOT avoided the historical tendency to build prisons in urban centers or very close to them, but El Salvador is the most densely populated country on the American continental shelf, with more than 300 inhabitants per square kilometer. The presence of CECOT is affecting thousands.

The nearest settlement, just over a kilometer away, is called El Milagro 77. I had to get there.

***

Wilfredo Escobar Portillo is 47 years old, suffers from chronic renal insufficiency, is poor and lives in El Milagro 77. The two streams that border this community to the east and west are today more voluminous and nauseating because of the raw or poorly treated fecal discharges that come down from CECOT.

-We used to catch crabs and fish here, but now, if a dog drinks the water, after a few days it gets sick and dies. It’s as if the water coming down has strong chemicals,” Wilfredo told me, next to the pedestrian walkway of the foul-smelling Perical River.

Now we have been talking for more than an hour outside his house, and he has convinced me that neither pollution nor his terminal illness – four peritoneal dialysis sessions a day – is what worries him most. Nor is it the mega-prison itself. What has been keeping Wilfredo awake at night since March 15 is the arbitrary detention of his son Winston Alexis Escobar Urbina, a young man imprisoned under the state of exception.

There are thousands of innocent people locked up by the Bukele Administration in El Salvador, but Alexis’ is one of the most unjustified cases.

At the age of 18, Alexis was already the family’s main provider. He is -was?- one of those tough young men who do not succumb to the poverty that marked their childhood. He worked as a construction worker for a contractor in Zacatecoluca – he was arrested and beaten on his way home from work -, he had saved to buy a beehive and produce honey, and to buy a modest number of chickens, breed them and sell them in the market. And all this while studying high school remotely. A young man whom it would not be difficult to describe as exemplary, but whom the Bukele government considers a terrorist.

Alexis is innocent not only because Wilfredo and Maria Norma Urbina, his mother, are telling me so. His boss, his neighbors and even the mayor of Tecoluca, who is from Nuevas Ideas, Bukele’s party, back him up. Alexis’ innocence is also supported, in a sworn statement before notary Natividad Argueta, by police agent J.F.M.G., who was assigned to the area for three years in an anti-gang unit.

Despite being warned by the notary that lying would expose him to the crime of false testimony, the anti-gang police officer was categorical: “The deponent declares that if he knew that young Winston Alexis Escobar Urbina was a member, collaborator or relative of gang structures, he would not expose himself or risk defending him, but [he does so because] he is aware and knows that he is an honest, hard-working person who respects all kinds of authorities.

Copies of this and the other exculpatory documents that Wilfredo has been compiling are known to the Salvadoran State, but as I write this chronicle, Alexis remains incarcerated and isolated in cell 33 of Sector 2 of La Esperanza Penal Center, Mariona. Eight months now.

-I was even happy when the soldiers came to the house that day to ask questions,” Wilfredo tells me, almost embarrassed.

Alexis wants – wanted? – to be a soldier. He had presented the documentation to the Armed Forces, he had passed all the filters and requirements, and at the beginning of April he expected to be called up to the 5th Infantry Brigade in San Vicente. That is why, even in spite of the state of exception, Wilfredo was happy when a platoon showed up at his house and asked for his son.

Surrealism in its purest form.

-Since the prison was built, soldiers walk past my house every day; some go down, others come up… and so on, night and day- Wilfredo tells me.

The militarization is excessive in the communities and hamlets surrounding CECOT. In El Milagro 77 — named after the kilometer of the highway where the exit is located — Alexis is not the only young man detained, despite the fact that for many years before the regime there was no gang presence. It has something to do with the fact that most of those who founded this settlement in 1998 — Wilfredo is one of them — were ex-guerrillas of the FPL, the Popular Liberation Forces.

For Wilfredo, he tells me in a sad and resigned tone, the construction of the mega-prison and the arbitrary detention of his son – which is literally consuming him – have a cause and effect relationship. This is why pollution and even his illness have taken a back seat.

Before visiting Wilfredo and other neighbors of El Milagro 77, before visiting their dead streams, I spent this Friday morning in the central park of Tecoluca. There I talked with César Cañas, a social and political activist. César is part of the MDT, the Movement for the Defense of the Land of Tecoluca, and is the candidate of the FMLN party for the municipal elections to be held in March 2024.

This young agronomist engineer has explained to me that the sudden construction of CECOT in his municipality began in a clandestine manner, without the environmental impact study required by the Environmental Law, nor consultations in the affected communities. The State did not even pay the municipality to build something like this, a multi-million dollar project.

“But the most serious thing is that it was built on the slopes of the volcano, in a water recharge zone,” César emphasized to me.

Another point that he mentioned, and that I will hear in all the interviews these two days, is that neither the works first, nor the administration of the mega-prison later, have generated jobs. It’s only a few Tecoluquenses that have benefited from a salary, among thousands of workers, custodians, administrators….

The morning conversation with Cesar happened on a park bench, while a platoon of the Armed Forces fluttered around, equipped as if they were going to fight in Gaza.

It is late and I am on my way out of El Milagro 77, a community where I have arrived on my own initiative. César has been the one who suggested to me that, in order to fully measure the impact of the contamination, I should go to the San Francisco Angulo community and the Cantarrana hamlet.

***

Félix Laínez has summoned me to his home in San Francisco Angulo at 8 o’clock this Saturday morning. The river that borders El Milagro 77 to the west is the one that 500 meters below bathes this community of Tecoluca, the closest to the municipality of Zacatecoluca.

It has not been difficult for me to find the house because everyone here -about 125 families- knows it. Felix is, in the purest sense of the word, a community leader. Born and raised in this corner of the country, he has been combing his gray hair for years; he is 55 years old.

I showed up on time, about five minutes ago, and his wife offered me water and a chair on the porch, although that word sounds pompous for this home that is rural and simple. Six meters from where I have sat, a cow grazes, and its mooing will coexist with this long conversation.

Felix now shows up sweaty and dressed for work, with wellies, a fisherman’s cap that he takes off to say hello and his knife sheathed on his shoulder. He is a farmer -corn, maicillo, beans; not rice anymore, since the price plummeted- and a cattle rancher, but on a small scale, he explains. In fact, he comes from feeding his cows… the cows he has left.

-Two of them have already died because of the water issue,” he repeats what he told me yesterday via WhatsApp.

His land is next to the now toxic river, once full of life. Beautiful crayfish used to come out, he says. Before CECOT he had 20 cows and a couple of oxen. Now he has only three cows; one of them is this one next to us. He sold the oxen last week.

Felix knows the basics of veterinary medicine, he invests in the health of his cattle and brags about having always had a robust, healthy, well-fed herd.

-The two cows that died, I left them in the paddock in the afternoon and they were dead the next day,” he tells me.

He heard of other dead cows in other communities also for having drunk from the rivers that flow down from Bukele’s mega-prison. He dug a big ditch at the beginning of the rainy season to store water, but, knowing that the dry season is upon us and he will depend on the river again, he has opted to sell them, one after the other.

He was also concerned that in the main markets, where local ranchers and farmers sell – San Vicente and especially Zacatecoluca – word has spread that everything from the area most affected by CECOT is contaminated.

-Here we have water all year round and there has always been a lot of vegetables: cucumbers, radishes, green beans, sweet peppers, loroco… But in the market for some time they have been asking where the produce comes from, and if you say it comes from 77, because that is what they tell us, they either don’t buy it or they want to take it away from you.

As a community leader, he has filed a formal complaint with the Tecoluca health unit, which depends on the Ministry of Health, but they have not listened to them; they have not even responded to his requests to analyze the water they are consuming, which is from wells, and Felix fears that all the rottenness emanating from the prison is infiltrating.

Felix is pessimistic, very pessimistic. He believes it is only a matter of time before the contamination spreads to all the land between CECOT and the Pacific Ocean. A triangle of some 300 square kilometers in which there are important population centers, such as Santa Cruz Porrillo, El Playón, Los Marranitos or San José de la Montaña.

-And it has value to be defending your community at this time, with this stunt by the regime- he tells me in a tone halfway between anger and dignity.

After an enriching conversation, I say goodbye to Felix and go to have lunch at Pollo Campestre in Zacatecoluca. As soon as I leave San Francisco Angulo and get far enough away from CECOT, all the messages and sounds accumulated during three hours fall all at once on my phone. The intermittent or non-existent signal, depending on the community and the company you have, is another of the consequences that affect the neighborhood.

After lunch, I now drive to the hamlet of Cantarrana, canton El Perical, still in Tecoluca. This settlement consists of barely thirty scattered houses, split in two by one of the pestilent rivers that flow down from Bukele’s mega-prison. There is only one access road to Cantarrana, which dies there; unpaved, of course.

Just before arriving, an old woman walks with a basket full of corn on her head; she is going to the mill. I greet her, introduce myself, ask.

-And here in Cantarrana, is the river also polluted?

-So they say. Today nobody washes there, nobody bathes there; only in the house they bathe.

In the village, there is a footbridge to cross the river. In all the communities I have visited I have been told that CECOT discharges before dawn and/or late at night; now, in the middle of the afternoon, the water runs cloudy, with patches of white foam, and the smell is strong.

On a riverside property, Fatima Alvarenga and Carlos Ernesto Pineda, 22 and 27 years old, are working in a bean field. Fatima repeats scenes I have been hearing since yesterday: pestilence, the occasional dead dog, useless water for washing….

Carlos Ernesto listens carefully a few meters away and leaves for a moment the shovel with which he is digging to say something he thinks is funny.

-Last week a watermelon seller came to Cantarrana and, as he saw the water running, he grabbed it with his hands to wash his face… Ooooff! Until he smelled it! It had happened before to others, but this one asked if he could come in to the house to get rid of the bad smell.

***

Today we are on our way to CECOT. Dusk.

I start my Kia Rio and leave Cantarrana with the feeling that, after two intense days of reporting, I have enough to write a worthy chronicle that portrays the concerns of the neighborhood of Bukele’s mega-prison. I am satisfied.

The excremental river that flows down from CECOT to Cantarrana, and from here towards the sea, is more direct, but to get by car to the prison gate is 3700 meters. Up to the first houses of San Francisco Angulo I now count one, two, three rivers and streams. Three in just 800 meters. Indeed a lot of water flows from the towering Chinchontepec volcano to the Pacific Ocean.

Just now I am passing in front of Felix’s house. “With this prison,” he told me this morning, “two things are going to happen: first, we are going to feel the contamination coming down from CECOT in the rivers; and then, our groundwater, the water we drink, will be contaminated. The first thing has already happened.

I continue in first and second gear up to the main road. Right, 200 meters to the solar plant that characterizes this landscape, I cross to the left, and I’m already on the shiny access road to CECOT.

I go with the recorder on and say this: “Let’s see what happens, but in journalism, as in life, sometimes it is better to ask for forgiveness than to ask for permission”.

I haven’t even gone 100 meters, and a military checkpoint: two soldiers with assault rifles in a precarious hut that gives them some shade and little else. One comes out to meet me, arm raised. I brake. I have the windows down.

-Good afternoon, can I…?

-Where are you going?

-Hello, good afternoon. My name is Roberto and I want to approach CECOT.

-You can’t.” The soldier was direct and firm.

-Nothing?

-Nothing.

-I’m doing a report on the contamination of the rivers; I come from the area of Angulo, of Cantarrana…

-But you can’t,” the soldier said firmly.

-Thank you. I’m going to go around the front.

What was bound to happen happened. I still had a kilometer to go to get to CECOT and, as it is a steep slope, I could not even see the walls or the watchtowers.

I finish the coverage in Tecoluca, San Vicente. It is getting dark. I return to San Salvador with the conviction that Bukele’s mega-prison will continue to be the talk of the town.

Divergentes (Original English version): https://www.divergentes.com/the-oppressed-neighbors-of-bukeles-mega-prison/

Los vecinos contaminados y oprimidos de la megacárcel de Nayib Bukele

Mañana al atardecer manejaré hasta los portones de la megacárcel de Bukele y pasará lo que tenga que pasar.

Ahora estoy en Tecoluca, en el departamento de San Vicente. Mañanée para venirme hasta el municipio que acoge la que el Gobierno de El Salvador ha publicitado como la cárcel más grande de Latinoamérica –del mundo, aseguran algunos–, y me he propuesto no regresarme a San Salvador sin al menos haber intentado acercarme.

Hay razones para la inquietud: el bukelismo tiene alergia al periodismo independiente; la zona está saturada de soldados y policías; el país acumula más de año y medio bajo un régimen de excepción que les da carta blanca para las detenciones arbitrarias; y ayer mismo fui encañonado, retenido y amenazado por un militar: cuando quise fotografiar el portón de otra cárcel, Zacatraz, como se conoce el Centro Penal de Máxima Seguridad Zacatecoluca, situado a apenas ocho kilómetros de la megacárcel.

Con la megacárcel de Bukele me refiero al CECOT, el acrónimo elegido para el Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo, quizá la obra más emblemática del primer quinquenio del presidente Nayib Armando Bukele Ortez.

En El Salvador, los miembros de las pandillas Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), Barrio 18-Sureños, Barrio 18-Revolucionarios y otras estructuras criminales menores, se consideran terroristas desde agosto de 2015, tras una resolución de la Sala de lo Constitucional.

Pero lo dicho: lo de acercarme al penal sin invitación será mañana al atardecer, cuando haya finalizado el reporteo de campo. Antes visitaré el casco urbano de Tecoluca y las comunidades aledañas, esas que vieron levantarse esta obra colosal de un día para otro –como quien dice–. Porque se ha hablado hasta la saciedad de los miles y miles presuntos emeeses y dieciocheros que están adentro, pero apenas nada de los vecinos: obreros, estudiantes, ganaderos, ancianos, agricultoras…

—Desde que lo abrieron, ese río hiede, pero hieeeeede… el agua hieeeeede… —me dirá mañana Fátima Alvarenga, joven agricultora del caserío Cantarrana, uno de los más afectados por la mierda que sale del penal; yo ahí lavaba la ropa, pero ahora, toca en la casa.

La contaminación es lo que más preocupa a la vecindad de la megacárcel de Bukele. Entre hoy y mañana escucharé de vacas muertas por beber de ríos otrora cristalinos, de producción agrícola menospreciada en los mercados y de una hediondez insufrible. También oiré quejas sentidas por la militarización, por las detenciones arbitrarias, por no haberse convertido siquiera en una fuente de empleo, por las fallas en la señal telefónica, por…

Y todas las personas que entrevistaré, todas sin excepción, me dirán que creen que lo peor está por venir. El número de privados de libertad recluidos ronda los 12 000, apenas un 30% de la capacidad anunciada.

***

Utilizar el “mega” para referirse a esta cárcel no es una hipérbole periodística más. El CECOT es en verdad colosal. La prisión ocupa 236 000 metros cuadrados, el equivalente a cinco veces el Zócalo de Ciudad de México. Rodearla caminando tomaría media hora… si permitieran acercarse.

Según los datos que el Gobierno suelta a discreción, cuenta con 37 torres de vigilancia, muros perimetrales de 11 metros de altura, siete anillos de seguridad, un hospedaje completo para los carceleros, otro para perros guardianes, una docena de talleres –de pintura, de elaboración de pupitres, de confección de ropa, de etcétera–, tecnología para que las audiencias judiciales sean virtuales y así los reos no abandonen las instalaciones, y su perímetro está vigilado por 600 soldados y 250 policías.

La megacárcel de Bukele tiene ocho pabellones para privados de libertad, completamente independientes uno del otro, y cada uno de ellos es tan extenso como el terreno de juego de la Bombonera, el estadio de Boca Juniors. Colosal.

Se anunció que el CECOT tendría su propia planta de tratamiento de aguas negras pero, si funciona, funciona fatal. Más luego entenderán.

El propio presidente de la República, Nayib Bukele, tuiteó que albergará a “40 000 terroristas, quienes estarán incomunicados del mundo exterior”, pero, transcurridos nueve meses desde su inauguración, la cifra de internos al 22 de octubre era de 12 149.

Pero más allá de la numeralia, el dato quizá más impactante es que en apenas ocho meses se construyó de la nada –de la nada–, sobre tierras de cultivo. Se manejó en secreto, pero un vecino de Tecoluca me contactó el 13 de mayo de 2022 para contarme que había maquinaria pesada en esa zona. Bukele anunció su megacárcel al mundo el 21 de junio, y la inauguró con bombo y platillo el 31 de enero de 2023. Recibió a sus primeros 2000 inquilinos el 24 de febrero.

Diseñar, adjudicar, construir y equipar una obra como el CECOT es consecuencia directa del régimen de excepción vigente desde el 27 de marzo de 2022 que, entre otras atribuciones, permite a la Administración Bukele asignar contratos a dedo.

Otro dato relevante es el lugar: el cantón El Perical de Tecoluca. “Decidimos hacerlo alejado de las ciudades”, anunció orgulloso el propio Bukele. Las elegidas fueron unas tierras ubicadas a 70 kilómetros de la capital, de fertilidad infinita, encajadas entre el altanero volcán Chinchontepec y el océano Pacífico; un territorio surcado por incontables ríos, riachuelos y quebradas, una zona de recarga acuífera.

Sobre lo de alejarlo de las ciudades, es cierto que el CECOT huyó de la tendencia histórica a construir centros penales en los núcleos urbanos o muy cerca de, pero El Salvador es el país más densamente poblado de la plataforma continental americana, con más de 300 habitantes por kilómetro cuadrado. La presencia del CECOT está afectando a miles.

El asentamiento más cercano, a poco más de un kilómetro en línea recta, se llama El Milagro 77. Tenía que ir.

***

Wilfredo Escobar Portillo tiene 47 años, padece insuficiencia renal crónica, es pobre y vive en El Milagro 77. Los dos riachuelos que demarcan esta comunidad a oriente y poniente son hoy más caudalosos y nauseabundos por las descargas fecales crudas o mal tratadas que bajan del CECOT.

—Fíjese que antes acá se cangrejeaba, se agarraban chimbolos y pescaditos, pero ahora, si un chucho toma ese agua, a los días comienza a enflacarse, hasta que se va. Como que trae químico fuerte el agua que baja– me dirá Wilfredo en un par de horas, junto a la pasarela peatonal del fétido río El Perical.

Ahora llevamos más de una hora de conversa fuera de su casa, y me ha convencido de que ni la contaminación ni su enfermedad en fase terminal –cuatro diálisis peritoneales al día– es lo que más le preocupa. Tampoco la megacárcel en sí. Lo que quita el sueño a Wilfredo desde el 15 de marzo es la detención arbitraria de su hijo Winston Alexis Escobar Urbina, un joven encarcelado bajo el régimen de excepción.

Son miles los inocentes encerrados por la Administración Bukele en El Salvador, pero el de Alexis es uno de esos casos que claman al cielo.

A sus 18 años, Alexis ya era el sostén económico familiar. Es –¿era?– uno de esos jóvenes arrechos que no se resignan a la pobreza que marcó su infancia. Trabajaba como peón para un contratista de Zacatecoluca –lo detuvieron y lo golpearon cuando venía de trabajar–, había ahorrado para comprar una colmena y producir miel, y para adquirir una modesta cantidad de pollos, reproducirlos y venderlos en el mercado. Y todo esto mientras estudiaba bachillerato a distancia. Un joven al que no costaría adjetivar como ejemplar, pero que el Gobierno de Bukele considera un terrorista.

Alexis es inocente no sólo porque así me lo están diciendo Wilfredo y María Norma Urbina, su madre. Lo respaldan su patrón, sus vecinos y hasta el alcalde de Tecoluca, que es de Nuevas Ideas, el partido de Bukele. La inocencia de Alexis también la avala, en una declaración jurada ante el notario Natividad Argueta, el agente policial J. F. M. G., que estuvo tres años asignado en el área, en una unidad antipandillas.

A pesar de ser advertido por el notario de que mentir lo exponía a incurrir en el delito falso testimonio, el policía antipandillas fue rotundo: “Me declara el deponente que si supiera que el joven Winston Alexis Escobar Urbina fuera miembro, colaborador o pariente de estructuras pandilleriles, no se expondría ni se arriesgaría a meter sus manos por él, pero [lo hace porque] está consciente y le consta que es una persona honrada, laboriosa y respetuosa con toda clase de autoridades”.

Copias de este y los demás documentos exculpatorios que Wilfredo ha venido recopilando los conoce el Estado salvadoreño, pero mientras yo escribo esta crónica, Alexis sigue encarcelado e incomunicado en la celda 33 del Sector 2 del Centro Penal La Esperanza, Mariona. Ocho meses ya.

—Si yo hasta me alegré cuando los soldados llegaron a la casa aquel día a preguntar– me dice Wilfredo, casi apenado.

Alexis quiere –¿quería?– ser soldado. Había presentado la documentación en la Fuerza Armada, había pasado todos los filtros y requisitos, y a inicios de abril esperaba ser llamado a filas en la 5ª Brigada de Infantería, en San Vicente. Por eso, incluso a pesar del régimen de excepción vigente, Wilfredo se alegró cuando un pelotón se presentó en su casa y preguntó por su hijo.

Surrealismo en estado puro.

—Desde que se construyó la cárcel, los soldados pasan frente a mi casa a diario; unos bajan, otros suben… y así noche y día– me dice Wilfredo.

La militarización es desmesurada en los cantones y caseríos aledaños al CECOT. En El Milagro 77 –se llama así por el kilómetro de la carretera en la que está el desvío– Alexis no es el único joven detenido, a pesar de que desde muchos años antes del régimen no había presencia de pandillas. Algo tiene que ver con que la mayoría de quienes fundaron este asentamiento en 1998 –Wilfredo es uno de ellos– eran exguerrilleros de las FPL, las Fuerzas Populares de Liberación.

Para Wilfredo, me dice con una cadencia entristecida y resignada, la construcción de la megacárcel y la detención arbitraria de su hijo –que lo está consumiendo, literalmente– tienen una relación causa-consecuencia. Por eso, la contaminación y hasta su enfermedad han pasado a un segundo plano.

Antes de visitar a Wilfredo y demás vecinos de El Milagro 77, de conocer sus riachuelos muertos, la mañana de este viernes la he pasado en el parque central de Tecoluca. Ahí he conversado con César Cañas, activista social y político. César es parte del MDT, el Movimiento por la Defensa de la Tierra de Tecoluca, y es el candidato del partido FMLN para las elecciones municipales que se celebrarán en marzo de 2024.

Este joven ingeniero agrónomo me ha explicado que la repentina construcción del CECOT en su municipio se inició de manera clandestina, sin el estudio de impacto ambiental que establece la Ley de Medio Ambiente, ni consultas en las comunidades afectadas. El Estado ni siquiera pagó a la municipalidad por levantar algo así, una cifra de muchos ceros por ser una obra millonaria.

“Pero lo más grave es que se construyó en las faldas del volcán, en una zona de recarga hídrica”, me ha enfatizado César.

Otro punto que ha mencionado, y que escucharé en todas las entrevistas estos dos días, es que ni las obras primero, ni la administración de la megacárcel después, han generado puestos de trabajo. Se pueden contar con los dedos de las manos los tecoluquenses que se han beneficiado con un salario, entre miles de obreros, custodios, administrativos…

La conversación mañanera con César ha sido en una banca del parque, mientras un pelotón de la Fuerza Armada revoloteaba alrededor, equipados como si fueran a combatir en Gaza.

Es tarde y voy de salida de El Milagro 77, comunidad a la que he llegado por iniciativa propia. César ha sido quien me ha sugerido que, para medir a cabalidad el impacto de la contaminación, debería acercarme sí o sí al cantón San Francisco Angulo y al caserío Cantarrana.

***

Félix Laínez me ha citado en su hogar, en San Francisco Angulo, a las 8 de la mañana de este sábado. El río que bordea al poniente El Milagro 77 es el que 500 metros abajo baña este cantón de Tecoluca, el más pegado al municipio de Zacatecoluca.

No me ha costado dar con la casa porque acá todo mundo –unas 125 familias– lo conoce. Félix es, en el sentido más limpio de la palabra, un líder comunitario. Nacido, criado y madurado en este rincón del país, peina canas desde hace años; tiene 55.

Me he presentado puntual, hace unos cinco minutos, y su esposa me ha ofrecido agua y silla en el porche, aunque esa palabra resuena pedante para esta vivienda que transpira ruralismo y sencillez. A seis metros de donde me he sentado, una vaca rumia, y salpimentará con sus mugidos esta larga conversación.

Félix aparece ahora sudado y vestido de faena, con botas de agua, un gorro pescador que se quita para saludar y el corvo envainado al hombro. Es agricultor –maíz, maicillo, frijol; arroz ya no, desde que el precio se desplomó– y ganadero, pero en pequeño, aclara. Viene de hecho de alimentar a sus vacas… a las vacas que le quedan.

—Ya se me murieron dos por la cuestión del agua– me repite lo que me comentó ayer vía WhatsApp.

Sus terrenos quedan junto al río ahora tóxico, otrora lleno de vida. Cangrejonas hermosas salían, dice. Antes del CECOT tenía 20 vacas y una yunta de bueyes. Ahora sólo tiene tres vacas; una de ellas, esta que está con nosotros. Los bueyes los vendió la semana pasada.

Félix sabe lo básico de veterinaria, se esfuerza e invierte en la salud de sus reses y se jacta de haber tenido siempre un ganado robusto, sano, bien alimentado.

—Las dos vacas que se me murieron las fui a dejar al potrero en la tarde y, al día siguiente, muertas– me dice.

Escuchó de otras vacas muertas en otras comunidades también por haber tomado de los ríos que bajan de la megacárcel de Bukele. Cavó al inicio de la estación lluviosa una gran zanja para almacenar agua, pero, sabiendo que está encima la temporada seca y que volverá a depender del río, ha optado por venderlas, una tras otra.

Le preocupaba también que en los mercados principales, donde venden los ganaderos y agricultores locales –San Vicente y sobre todo Zacatecoluca– se ha corrido la voz de que todo lo que proviene de la zona más afectada por el CECOT está contaminado.

—Acá tenemos agua todo el año y siempre ha salido mucha hortaliza: pepinos, rábanos, ejote, chile dulce, loroco… Pero en el mercado de un tiempo están preguntando de dónde viene el producto y, si uno responde que del 77, porque así nos dicen, o no lo compran, o se lo quieren bajar a uno.

Como líder comunitario, ha presentado una queja formal en la unidad de salud de Tecoluca, dependiente del Ministerio de Salud, pero no les han hecho caso; ni siquiera han accedido a sus peticiones de que analicen el agua que están consumiendo, que es de pozos, y Félix teme que toda la podredumbre que emana la cárcel esté infiltrándose.

Félix es pesimista, muy pesimista. Cree que es cuestión de tiempo que la contaminación se extienda a todas las tierras comprendidas entre el CECOT y el océano Pacífico. Un triángulo de unos 300 kilómetros cuadrados en los que hay importantes núcleos poblacionales, como Santa Cruz Porrillo, El Playón, Los Marranitos o San José de la Montaña.

—Y tiene valor estar defendiendo en estos momentos a tu comunidad, con esta carambada del régimen– me dice con un tono a medio camino entre el enojo y la dignidad.

Tras una plática que he sentido enriquecedora, me despido de Félix y voy a almorzar al Pollo Campestre de Zacatecoluca. Apenas salgo de San Francisco Angulo y me alejo lo suficiente del CECOT, caen de un solo en mi teléfono todos los mensajes y sonidos acumulados durante tres horas. La señal intermitente o inexistente, en función de la comunidad y la compañía que uno tenga, es otra de las consecuencias que afectan a la vecindad.

Almorzado, manejo ahora hacia el caserío Cantarrana, cantón El Perical, siempre en Tecoluca. Este asentamiento son apenas una treintena de viviendas desperdigadas, partidas en dos por uno de los ríos pestilentes que bajan de la megacárcel de Bukele. Hay una sola calle de acceso a Cantarrana, que ahí muere; sin asfaltar, por supuesto.

Justo antes de llegar, una anciana camina con un huacal lleno de maíz en la cabeza; va al molino. Saludo, me presento, pregunto.

—¿Y acá en Cantarrana el río también está contaminado?

—Así dicen. Hoy nadie lava ahí, nadie se baña; sólo en la casa se bañan.

En el caserío, una pasarela peatonal permite atravesar el río. En todas las comunidades que he visitado me han comentado que el CECOT hace descargas antes del amanecer y/o entrada la noche; ahora, a media tarde, el agua corre turbia, con parches de espuma blanca, y el olor es fuerte.

En un predio en la ribera, Fátima Alvarenga y Carlos Ernesto Pineda, de 22 y 27 años de edad, están trabajando en un frijolar. Fátima me repite escenas que vengo escuchando desde ayer: pestilencias, algún que otro perro muerto, aguas inútiles para lavarse o para lavar…

Carlos Ernesto escucha atento a unos metros y deja por un momento la pala dúplex con la que agujerea la tierra para contar algo que considera gracioso.

—La semana pasada vino a Cantarrana un vendedor de sandías y, como vio el agua correr, la agarró con las manos para lavarse la cara… ¡Jeiiiiin! ¡Hasta que sintió el patín! Ya le había pasado antes a otros, pero a este no le dio pena y nos pidió pasar a la casa para quitarse el mal olor.

***

Hoy sí, ruta al CECOT. Atardece.

Enciendo mi Kia Rio y salgo de Cantarrana con la sensación de que, tras dos días intensos de reporteo, me llevo mimbres para hilar una crónica digna que retrate las preocupaciones de la vecindad de la megacárcel de Bukele. Voy satisfecho.

El río excrementado que baja del CECOT a Cantarrana, y que desde acá enfila hacia el mar, es más directo, pero llegar en carro hasta el portón del penal son 3700 metros. Hasta las primeras casas de San Francisco Angulo cuento ahora uno, dos, tres ríos y riachuelos. Tres en apenas 800 metros. En verdad fluye mucha agua desde el altanero volcán Chinchontepec al océano Pacífico.

Justo ahora estoy pasando frente a la casa de Félix. “Con esta cárcel –me ha dicho esta mañana– van a suceder dos cosas: primero, vamos a sentir la contaminación que baja del CECOT en los ríos; y luego, se nos contaminará el agua subterránea, la que tomamos. Lo primero ya se ha cumplido”.

Continúo en primera y en segunda hasta la carretera principal. Derecha, 200 metros hasta la planta solar que singulariza este paisaje, cruzo a la izquierda, y ya estoy sobre la reluciente calle de acceso al CECOT.

Voy con la grabadora encendida y digo esto: “A ver qué pasa, pero en esto del periodismo, como en la vida, a veces es mejor pedir perdón que pedir permiso”.

No he recorrido ni 100 metros, y un control militar: dos soldados con fusiles de asalto en una precaria caseta que les garantiza algo de sombra y poco más. Uno sale a mi encuentro, brazo en alto. Freno. Voy con los vidrios bajos.

—Buenas tardes, ¿se puede…?

—¿Adónde va?

—Hola, muy buenas tardes. Mi nombre es Roberto y quiero acercarme al CECOT.

—No se puede– lacónico y firme el soldado.

—¿Nada?

—Nada.

—Estoy haciendo un reportaje sobre la contaminación de los ríos; vengo del sector de Angulo, de Cantarrana…

—Pero no se puede– lacónico y firme el soldado.

—Vaya… Gracias. Voy a dar la vuelta ahí delante.

Ha pasado lo que tenía que pasar. Me faltaba aún un kilómetro hasta el CECOT y, como es una cuesta algo pronunciada, ni siquiera he alcanzado a ver los muros o las torres de vigilancia.

Doy por cerrado el reporteo en Tecoluca, San Vicente. Atardece. Me regreso a San Salvador con la convicción de que la megacárcel de Bukele seguirá dando de qué hablar. Al tiempo.

Divergentes: https://www.divergentes.com/los-vecinos-contaminados-y-oprimidos-de-la-megacarcel-de-nayib-bukele/