In 2023, after over a year of the state of exception, the Minister of Justice and Public Security of El Salvador accepted that one out of every ten arrested individuals would be released after being found innocent.

DW spoke with two of them – a man and a woman – who were supported by the NGO Socorro Jurídico Humanitario and were able to regain their freedom. These are their accounts.

“It’s hard for one to recover; perhaps one never fully recovers”

“Alfredo” is afraid and has recurring nightmares. He does not want his name or whereabouts to be published. He has spent 28 years of his life in the Salvadoran countryside. When arrested, he worked on a coffee plantation with his father, grandfather, two brothers-in-law, and an aunt. They were all detained, but the arresting police officers did not have an arrest warrant.

“We had been stopped and searched several times before, and they had found nothing, so they let us go,” he says in a low voice. But that day, “they took us to the police station, where the sergeant wanted us to admit to everything they were inventing. He told us that we were already known as gang members in the system, and that’s what we would be from then on.”

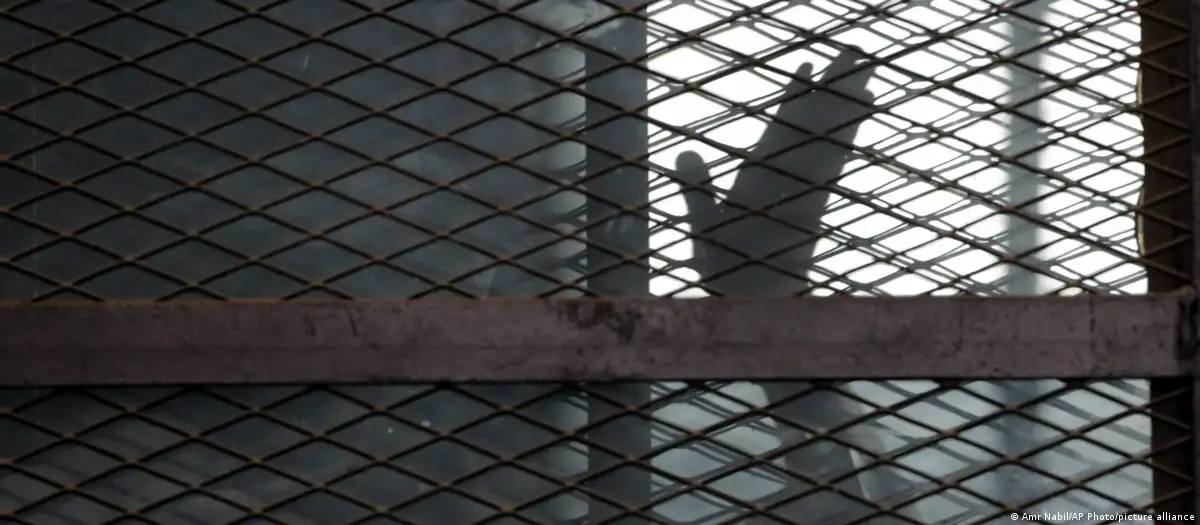

The young farmer recalls spending the night in the holding cells of a municipality 82.7 km from San Salvador. Later, they were transferred to the Izalco prison, 57.1 km from the capital. That was in May 2022, and two months later, he was taken to the Mariona prison (9.6 km away). He claims that during the second transfer, he had scars on his wrists from the handcuffs.

Upon arriving at Izalco prison, “a guard told us to line up because, as newcomers, we were in for a ‘welcome.’ Then they started beating all of us. Everyone, regardless of age. The guards kicked us, slapped us with their batons. They stripped us naked and started hitting us on the ribs, heels, and head.”

“After that, they made us kneel on a gravel field, naked, and then they put us in cells. Around 8 p.m., the person they told us was the director of Izalco arrived with some guards and started spraying gas in the cells, saying it was part of the ‘welcome.’ I felt itching and suffocation. The more you breathe, the more your throat feels like it’s closing. It’s a strange sensation that I had never experienced before,” he continues.

“Alfredo” claims to have experienced that kind of mistreatment from the guards several times and that “the gang members would beat people.” The experience has left lasting effects: “Sometimes at night, I dream they are beating me. Or sometimes I dream that they are beating someone else and they die. It’s difficult to recover from all of that, perhaps one never fully recovers.”

“I saw people die. On the day we arrived, I saw two: an elderly person and a young man,” he says. He recalls that from the beatings during the so-called welcome, “someone’s head was smashed, and they said that’s why he was convulsing, trembling on the floor. They put him in a bag and took him away.”

“I saw a 22-year-old guy, one of the first to die in the cell where I was. His ribs were fractured, and for about six days, we kept screaming for help, but they only came to see him, and the guards would say, ‘Call me when he dies.’ And that’s practically what happened because they didn’t pay attention to him until one morning during the count, several hours after he had already died. All of that brings back bad memories,” he comments.

“Alfredo” was released from prison thanks to a polygraph test that he passed. In his community, there were “plenty of gang members for years. Those people had threatened me three times: twice that they would kill me and once that I should leave my home. How can one have any connection with them if they wanted to kill him?”

Thus, after months, “Alfredo” was able to return home, but his family members remain imprisoned. Despite his freedom, he explains that his life has worsened because he now carries the stigma of having been in prison, which prevents him from finding jobs. “What hopes or opportunities can I have if my papers are practically stained?” Despite being innocent, he complains, “society, instead of helping, seems to want to hang you.”

“The female gang members are the leaders”

Dolores Victoria Almendariz, a 48-year-old janitor, is not afraid. On the contrary, she wants her name to be known and expresses her anger.

“I was calm, they messed with me,” says the defiant union leader from the Municipality of Cuscatancingo, 11.3 km from the capital. The single mother of six children, three infants, has been a union leader for years and claims that “here, being a defender of rights has consequences.”

“One is a victim of the gangs and the government. Here, the honest person is the one who goes to jail. The one who wants to kill or steal runs away,” she asserts.

Almendariz’s arrest took place in 2022 after she participated in a meeting to organize a protest for the lack of labor benefits in the Municipality. She says her colleagues argued that the state of exception was still in effect, so they couldn’t close the premises or engage in any demonstration. “I told them that the state of exception is for criminals, not for hardworking people. Those who stand up for their rights shouldn’t end up in prison,” she recounts.

However, even before the union protest occurred, “I had five police officers knocking on my door. After they searched the house in anger, a police officer told me, ‘You’re coming with us, we’re going to ask you some questions.’ When we arrived at the police station, he told me, ‘You’re under arrest.'”

“I had been kidnapped by the police officers, not the gang members. The next day, they brought some documents for me to sign. When I started reading, I saw that it said it was for extortion and kidnapping. I told them I wouldn’t sign and didn’t sign anything,” she continues.

“From there, they took me to the holding cells in Zacamil. They processed me, gave me a little card. Imagine a criminal labeling you! Because a police officer is a uniformed criminal, and it hurts because I pay them,” she complains. After Zacamil, Almendariz says she was transferred to the Women’s Prison in Ilopango, 12.9 km from San Salvador. She was imprisoned for seven months.

“The first thing that affects your morale and makes you uncomfortable is arriving at a prison where you see those tattooed women mistreating you. The gang members are the bosses of all the cells,” she says, adding that innocent women are “with convicts, gang members, all kinds of people. And everyone sleeps next to you. You live uncertain whether you’ll see the next day.”

The union leader claims to have identified a guard who “enjoyed spraying gas on people. Also, there was a cruel woman who punished others.” That officer “hanged a girl who didn’t know she was pregnant.”

Almendariz explains that one common punishment is “they put the handcuffs on your hands and hang you from a cyclone fence. You end up touching the ground with your big toes.” During that punishment, she says she saw the girl “bleeding a lot. We saw that they only threw water on her to make the blood flow, but they didn’t stop it. She hung there all day and all night. When they took her down the next day, I gave her 36 towels because she was in bad shape. I told her to ask for a dilation and curettage, but since they didn’t take us for consultations, she lost the baby.”

Months later, she was transferred to Apanteos, 72.7 km from the capital. There, “I saw the prison director kicking a female inmate. He threw her to the ground. There was screaming. Then, not only him but also another boss, the guard, and the female guard started hitting her. They took her away by dragging her by one hand. I never saw her again.”

She was released after a special hearing, where she was imposed a bail of one thousand dollars, which she was able to pay with the help of her union. According to her estimation, her arrest had the desired results: “My union colleagues are scared, and they say they’re not willing to spend seven months in prison,” so they haven’t protested anymore.

DW requested a statement from the Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman (PDDH), but there was no response at the time of closing this article.

DW: https://www.dw.com/es/uno-es-víctima-de-las-maras-y-del-gobierno-en-el-salvador/a-66784191

“Uno es víctima de las maras y del Gobierno” en El Salvador

En 2023, y luego de más de un año del régimen de excepción, el ministro de Justicia y Seguridad Pública de El Salvador aceptó que una de cada diez personas capturadas fuera liberada tras ser encontrada inocente.

DW habló con dos de ellas -un hombre y una mujer- que fueron apoyados por la ONG Socorro Jurídico Humanitario y así lograron su libertad. Estos son sus relatos.

“Cuesta que uno se recupere, quizás no se recupera del todo”

“Alfredo” tiene miedo y pesadillas recurrentes. No quiere que publiquemos su nombre ni información sobre su paradero. Cuenta con 28 años de vida transcurrida en el campo salvadoreño. Cuando fue capturado, estaba trabajando en una finca de café junto a su padre, su abuelo, dos cuñados y una tía. Todos fueron detenidos, pero los policías que los arrestaron no llevaban orden de captura.

“Varias veces ya nos habían parado, nos habían registrado y no habían encontrado nada, así que nos dejaban ir”, declara con voz baja, pero ese día “nos llevaron a la delegación y ahí el sargento quería que aceptáramos todo lo que se estaba inventando. Nos dijo que nosotros ya éramos pandilleros. ‘Ya están en el sistema que eso (es lo que) son y eso van a ser de aquí para adelante’, nos dijo”.

El joven agricultor recuerda que pasó la noche en las bartolinas de un municipio ubicado a 82.7 km de San Salvador. Luego, los hombres fueron trasladados al penal de Izalco, a 57.1 km de la capital. Eso fue en mayo de 2022, dos meses después lo llevaron al penal de Mariona (a 9.6 km). Asegura que, en el segundo traslado, iba con cicatrices de los grilletes en sus muñecas.

En la primera cárcel, al llegar a Izalco, “un custodio dijo que hiciéramos fila porque, por ser nuevos, nos tocaba la ‘bienvenida’. Entonces empezaron a golpearnos a todos. A todos, sin importar si eran ancianos o jóvenes. Los custodios nos empezaron a dar patadas, manotazos, con sus garrotes. Nos desnudaron y nos empezaron a pegar del lado de las costillas, en los talones de los pies, en la cabeza”.

“Después, nos tuvieron hincados en una cancha, con grava, desnudos y de ahí nos metieron para las celdas. Como a las ocho de la noche, llegó el que nos dijeron que era el director de Izalco con unos custodios y empezó a rociar gas en las celdas, porque dijo que era parte de la ‘bienvenida’. Yo sentí picazón y asfixia. A uno, entre más respira, como que se le va cerrando la garganta. Es una sensación bien rara que yo jamás había experimentado”, continúa.

“Alfredo” asegura que vivió ese tipo de maltrato de los custodios varias veces y que también “los pandilleros le pegaban a la gente”. Toda la experiencia ha dejado secuelas: “A veces, en las noches sueño que me están pegando. O a veces sueño que le están pegando a otro y que se muere. De todo eso, cuesta que uno se recupere, quizás no se recupera del todo”.

“Yo vi a gente morir. Solamente el día que llegamos vi a dos: una persona de avanzada edad y un muchacho”, afirma. Según recuerda, de los golpes de la denominada bienvenida, “a uno le habían reventado el lado de la cabeza y dijeron que por eso estaba convulsionando, porque temblaba en el suelo. De ahí, en una bolsa lo echaron y se lo llevaron”.

“Vi a un muchacho que tenía 22 años, que fue de los primeritos que murió dentro de la celda donde yo estaba. Le habían fracturado las costillas y todos, como por seis días, pasamos gritando que le ayudaran, pero sólo llegaban a verlo y decían los custodios ‘cuando se muera, me llaman’. Y prácticamente así fue ,porque no le hicieron caso hasta que un día, en la mañana que salimos al conteo, ya él tenía varias horas de haber fallecido. Todo eso le trae recuerdos malos a uno”, comenta.

Su salida de la cárcel se dio gracias al polígrafo al que fue sometido y que pasó. En su comunidad, por años, hubo “bastante pandilleros. A mí, esas personas, me habían amenazado tres veces: dos veces que me iban a matar y otra que me fuera de la casa ¿Uno cómo va a tener vínculos con ellos si querían matarlo?”.

Así, y luego de meses, “Alfredo” pudo regresar a su casa, pero sus familiares siguen presos. Pese a su libertad, explica que su vida ha empeorado, porque ahora tiene el estigma de haber estado en prisión, lo que le impide acceder a trabajos. “¿Qué esperanzas o qué oportunidades puedo tener, si prácticamente los papeles los tengo manchados?” y reclama que, pese a ser inocente, “la sociedad, en lugar de ayudarle a uno, como que lo quieren colgar”.

“Las pandilleras son las jefas”

Dolores Victoria Almendariz, una ordenanza de 48 años, no tiene miedo. Por el contrario: quiere que se sepa su nombre y que está molesta.

“Yo estaba tranquila, ellos se metieron conmigo”, afirma desafiante la sindicalista de la Alcaldía de Cuscatancingo, a 11.3 km de la capital. La madre soltera de seis hijos, tres de ellos infantes, es líder sindical desde hace años y asegura que “aquí, ser defensora de derechos trae consecuencias”.

“Uno es víctima de las maras y del Gobierno. Aquí, el honrado es el que va a la cárcel. El que lo quiere asesinar, o el que le roba, sale corriendo”, asegura.

La captura de Almendariz se dio en 2022 luego de que ella participara en una reunión para organizar una protesta por la falta de prestaciones laborales en la Alcaldía. Cuenta que sus compañeros alegaron que estaba vigente el régimen de excepción, por lo que no podrían hacer un cierre del local o alguna manifestación. “Yo les dije que el régimen es para delincuentes, no para personas trabajadoras. El que vela por sus derechos no tiene por qué ir a parar a un penal”, cuenta.

No obstante, y antes de que hicieran la protesta sindical, “tenía a cinco policías tocándome la puerta. Después de que revisaron la casa enfurecidos, me dijo un policía ‘nos va a acompañar, le vamos a hacer unas preguntas’. Cuando llegamos a la delegación, me dijo ‘usted queda detenida'”.

“Había sido secuestrada por los agentes policiales, ya no por los mareros. El siguiente día, llegaron con unas actas para que las firmara. Cuando yo empecé a leer, veo que decía que era por extorsión y por secuestro. Les dije que no iba a firmar y no firmé nada”, continúa.

“De ahí, me llevaron a las bartolinas de Zacamil. Ahí me ficharon, me pusieron un cartoncito. ¡Imagínese un delincuente etiquetándolo a uno! Porque un policía es un delincuente uniformado y con dolor porque yo le pago”, reclama. Luego de Zacamil, Almendariz dice que fue trasladada a Cárcel de Mujeres, en Ilopango a 12.9 km de San Salvador. Estuvo presa siete meses.

“Lo primero que a Ud. le baja la moral, y con lo que se siente incómoda, es llegar a una prisión donde ve a aquellas mujeres tatuadas que la maltratan. Las pandilleras son las jefas de todas las celdas”, cuenta, y añade que ahí las mujeres inocentes están “con penadas, con mareras, con toda clase de gente. Y todos duermen a la par suya. Usted vive con aquello que no sabe si va a amanecer el siguiente día”.

La sindicalista asegura que identificó a un custodio que “se deleitaba echándole gas a uno. También, estaba una mujer cruel para castigar”. Esa agente “colgó a una muchacha, que no sabía que estaba embarazada”.

Almendariz explica que, uno de los castigos comunes administrados es que “con las esposas, se las ponen en las manos y las cuelgan de una tela ciclón. Usted queda topando el suelo con los dedos gordos de los pies”. Durante ese castigo, la sindicalista asegura que vio que a la muchacha “le salía un montón de sangre. Nosotras veíamos que sólo le tiraban agua para que le corriera la sangre, pero nada que la bajaron. Ahí estuvo ella guindada todo el día y toda la noche. Cuando la bajaron, al siguiente día, yo le di 36 toallas porque ella había quedado mal. Yo le dije que pidiera que le hicieran un legrado, pero como no lo sacaban a uno ni a consulta, ella perdió el bebé”.

Meses después, fue trasladada a Apanteos, a 72.7 km de la capital. Ahí “vi cuando el director del centro penal agarró a patadas a una reclusa. La tiró al suelo. Era una gritadera. Luego ya no sólo le pega él, sino que le pegaba también otro jefe, el custodio y la custodia que estaban ahí. La agarraron arrastrada de una mano y así se la llevaron. Yo ya no la volví a ver”.

Su liberación se dio tras una audiencia especial, en la que le impusieron una fianza de mil dólares que pudo pagar con la ayuda de su sindicato. Su detención, según estima, tuvo los resultados esperados: “Mis compañeros del sindicato están atemorizados y dicen ellos que no están dispuestos a ir a parar siete meses a una prisión”, por lo que ya no han protestado.

DW solicitó la postura de la Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos (PDDH), pero al cierre de esta nota no hubo respuesta.

DW: https://www.dw.com/es/uno-es-víctima-de-las-maras-y-del-gobierno-en-el-salvador/a-66784191