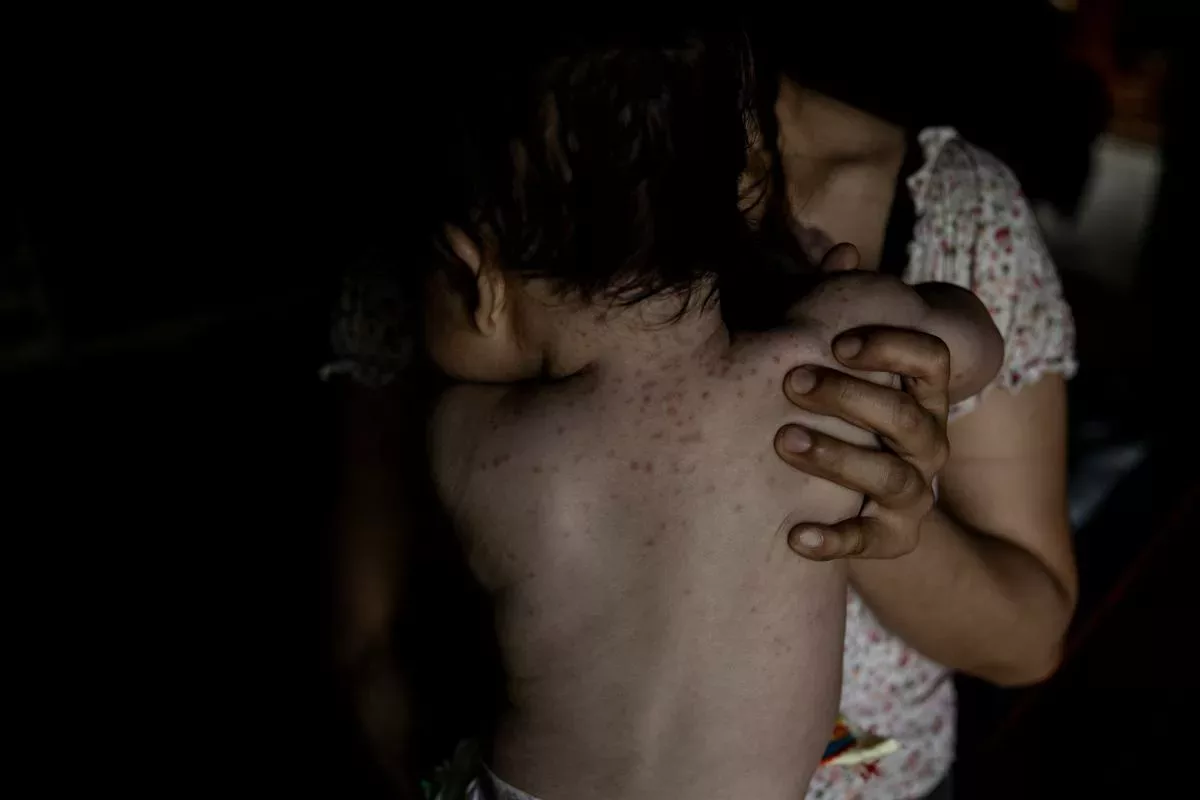

Andrés was released from the Izalco prison on May 29, 2023, with his back covered in rashes. He suffers from scabies, caused by moisture and dirt. During the five months Andrés was in prison, he received no medication for scabies or other illnesses he experienced during his confinement.

Andrés, desperate, cried from the itching. When the red bumps spread across his back and neck, he was just five months old.

A newborn is innocent in the literal sense of the word. Obviously, they were not captured or prosecuted by the exceptional regime, but they became victims of the repressive prison policy that prevented their medical check-ups before and after birth. Their access to hygiene items brought by their families was limited, and Penitentiary Centers denied them medication to treat scabies or fevers they experienced in the Izalco penitentiary farm. Even today, Andrés’s body shows the aftermath of that suffering during his imprisonment.

And he was not the only innocent one subjected to these abuses. Between December 2022 and May 2023, Penitentiary Centers isolated about thirty newborns due to a fungal infection in the Izalco penitentiary farm. This is what a woman, whom we will call Flor, the mother of Andrés, captured during the exceptional regime for the crime of terrorist organizations but released a few months later due to lack of evidence, reports.

According to the State itself, she is not affiliated with any gangs, nor are her tattoos related to these groups. However, she spent thirteen months in prison under the exceptional regime. The police arrested her for terrorist organizations on April 17, 2022, but documents from the Specialized Instruction Court C2 of San Miguel detail that she was prosecuted for illicit associations, without compelling evidence to this day. “This communication orders her immediate release if no pending crime exists,” states a document sent by the court to the Izalco prison on May 17, 2023.

“There were about 30 children isolated due to scabies, all babies. They isolated those first ones because they isolated a group, and supposedly they didn’t give them medication, they just isolated them for the sake of isolating them. The mothers combined creams with antibiotics and other things to help the children’s rashes go away. Or they would bathe them with bleach and laundry detergent because there was no other option, they didn’t give them any medication there. That’s how the poor children had to be treated, and yes, their rashes would go away.”

“Did the authorities know that mothers were bathing their children with bleach and laundry detergent?” El Faro asked Flor on June 5, 2023, during an over an hour and a half-long interview.

“No, but it was the only medicine available because they didn’t provide any medication. If they didn’t give you anything to apply on the rashes, you didn’t have any. I never bathed my child with bleach because I was afraid, but the mothers who dared… just to see their children better… because they (Penitentiary Centers) didn’t care about providing medication.”

Flor refused to bathe her baby with bleach or laundry detergent and made her own medicine. First, she negotiated with her fellow prisoners for pills with antibiotic properties. Then, like an alchemist, she crushed the pills and mixed them with her vaginal creams. Finally, she improvised a kind of saline solution with water and salt to bathe Andrés every day. The baby improved a little.

Flor still doesn’t understand why her son and the other babies contracted scabies. She describes the prison as a place with sufficient ventilation, regular access to clean water, and clean bathrooms. “What we tried to do as inmates was to keep it clean, but even then… the children would always get covered in rashes. They told us it was because of mites in the mattresses.”

On August 17, 2021, the Legislative Assembly, controlled by President Nayib Bukele, approved the “Nacer con Cariño” law to “guarantee the rights of women from pregnancy, as well as the rights of girls and boys from conception, during birth and the newborn stage.” Despite the law prioritizing the health rights of mothers and their babies, Andrés did not receive prenatal care in prison. The prison clinic did not provide medicine to treat the illnesses of the mother and her baby, and Penitentiary Centers did not deliver the medications brought by his grandmother in the packages. “Now that I’m out, I realize that my mom was sending me medicine, vitamins, and I never received any of that,” says Flor.

Andrés did not benefit from the “Nacer con Cariño” law. He was born at the Jorge Mazzini Hospital in Sonsonate and was transferred to the Izalco penitentiary farm three days later. His welcome to the world was the exceptional regime, a state policy that, according to testimonies from released prisoners and human rights reports, has normalized the torture of inmates, in some cases leading to death. Other common practices include lack of communication with relatives and lawyers, a meager diet, suspension of medical treatments, and lack of medication for inmates with illnesses.

Since late January this year, El Faro has repeatedly requested interviews with officials from the Press Offices of Penitentiary Centers, Police, Prosecutor’s Office, and Ministry of Security. Attempts have been made through letters left at those offices, emails, WhatsApp messages, and phone calls. Not a single space has been granted to discuss the arbitrary detentions under the regime. This pattern is not limited to the government’s security sector but is evident across all public institutions when faced with requests from this media outlet.

“Background, that was my crime”

On May 19, 2019, the police arrested a man transporting ten packages of marijuana and a portion of cocaine in the trunk of a car. Flor was accompanying the detained man and was prosecuted and sentenced to community service for her involvement.

On April 17, 2022, she was at home on probation, working with her mother in a juice-selling business and waiting for the judicial system to assign her a place to fulfill her community service. However, at two o’clock in the afternoon that day, as she was getting ready to go buy oranges with her mother in San Miguel, the police arrived at her house and took her to a police station.

“He told me they were going to accompany them, and I asked, ‘Why?’ He said he didn’t know. I asked if there was an arrest warrant, and he said no, that they were just accompanying them. At the police station, he told me I was being detained for terrorist organizations. ‘Why?’ I said, ‘I’ve never killed anyone.’ When I went to the Prosecutor’s Office, the lawyer told me that everyone was being arrested because they had criminal records.”

Article 11 of the Constitution of the Republic establishes that no one “may be tried twice for the same cause.” The police violated this constitutional provision and used past cases as a basis for arrests during the exceptional regime. This was the case for Flor, who was waiting for a judicial order to begin her sentence. El Faro has also documented cases where detainees were arrested for having been declared innocent in the past, such as the case of Don Paco, a merchant from La Reina, Chalatenango, who died in Mariona with signs of a beating.

After her arrest, Flor was transferred to the Osicala prison cell. The next day, on April 18, she was taken to the Ilopango prison, and that’s when a surreal judicial process began for her. “The Prosecutor’s Office said they couldn’t tell us the charges for each person because of the number of us, but they accused all of us of illicit associations. We were about 50 people, people I didn’t even know.” Various humanitarian organizations have denounced mass judicial proceedings during the exceptional regime, where judges send dozens or even hundreds of defendants to prison after a brief hearing without presenting evidence that individualizes their participation in alleged crimes.

In the Ilopango prison, Flor shared a cell with 300 other women. The cell was overcrowded, with five people sleeping on a cot without a mattress. During the nights, the cell floor was so crowded that it was impossible to walk. The overcrowded conditions also led to a shortage of clean drinking water: “They only gave us two small containers of water to bathe.” Amidst such overcrowding and hardship, one day turned into a week, a month… when she had been imprisoned in Ilopango for a month and a half, Flor found out she was pregnant.

Abuse in Izalco

Flor was seven weeks pregnant when she was transferred with 11 other pregnant women from the Ilopango prison to the Izalco penitentiary farm. Upon arrival, the guards took away her few belongings: pajamas, a blanket, a cup, a food tray, and a prison uniform. The guards threw all of it in the trash.

The Izalco penitentiary farm houses female inmates who are mothers or close to giving birth. Although they require special medical attention and nutrition to ensure the good health of their babies, they are subjected to mistreatment in that place, as Flor experienced and recounts.

“The guards were repugnant. They treated all the pregnant women badly. They would make us stand in the sun, at noon. They made us fetch water while pregnant. Water trucks would come (to the Izalco penitentiary farm) because sometimes water didn’t arrive, so we had to fetch water. We had to go out and hang clothes for everyone in the cell. There were about 150 pregnant women.”

Flor identifies two guards as the main culprits of the mistreatment: a female guard known as “Sirena” and a penitentiary chief known as “el jefe Shangai” (the Shanghai boss). “Sirena’s group was the one that treated us badly and made us stand in the sun. The other guards would consider us, let us spend five minutes in the sun, and then let us sit in the shade. But when it was Sirena’s shift, we always had to stay in the sun. I felt weak, I could only see the white figure of my companions, my vision was blurry,” she recalls.

The jefe Shangai, on the other hand, tried to impose respect through physical and verbal abuse. “Sometimes he would say we looked like prostitutes from the street, that we had to respect him as if he were a god. We had to greet him, and if we didn’t, he insulted us and would make us do squats, even though we were pregnant. I saw a pregnant woman doing squats. We hoped that human rights organizations would notice.”

Flor was in dormitory one, the maternity sector of the Izalco penitentiary farm. The farm has a clinic staffed by two doctors. One of the doctors, Dr. Córdova, attended to Flor during her first consultation after her transfer in mid-June 2023. Flor remembers receiving prenatal pills, iron, and antibiotics during the first consultation, but she realized that those medications were expired. In the following months of her pregnancy, she had no medical check-ups.

The two doctors attended to the 150 pregnant women, women who had already given birth and their babies, and the inmates in the trust phase, mostly elderly. The two doctors were overwhelmed.

One day, during her eighth month of pregnancy, Flor felt a terrible pain in her stomach. Dr. Córdova gave her two omeprazole pills and sent her back to the dormitory. “I told the doctor I couldn’t bear the gastritis pain, and she said, ‘What do you want me to do? Go out, buy you an injection, and give it to you? There are no medicines here,’ she said.”

The two omeprazole pills had no effect, and the pain worsened at night. The doctor on duty examined her again and referred her to the Jorge Mazzini Hospital in Sonsonate, where she was diagnosed with gallstones. Flor needed surgery, but due to her pregnancy, it was not possible at that time. Instead, a nutritionist prescribed a diet for her. “I told them they wouldn’t give me the diet there (in the prison), that it was a lie. A doctor told me, ‘Oh God, dear, you’ll only pass through here with pain! You need a diet,’ she said. But when I returned to the prison, of course, they didn’t give me the diet.”

A month after those unbearable pains, on December 25, 2022, Andrés was born. He was a malnourished child, looking “yellowish,” according to his mother. The baby stayed in the hospital for three days, but his mother, as per security protocol, immediately returned to the Izalco prison after giving birth. Andrés spent the first three days of his life at the Mazzini Hospital without the company of his mother, despite the “Nacer con Cariño” law establishing the right to “immediate secure attachment through skin-to-skin contact after birth, allowing for breastfeeding and carrying the baby.”

Three days after his birth, Andrés entered the Izalco penitentiary farm and had two medical check-ups where he received vaccinations: the first at seven days old and the second at 40 days old. After that, there were no further medical check-ups or examinations for the baby.

Before contracting scabies, Andrés also had the flu and did not receive medical attention, according to his mother. “I told Dr. Córdova that the child was unwell and asked if she could give me a nasal aspirator to clear his mucus. ‘I don’t have nasal aspirators!’ she said, and she yelled at me, turned around, and gave me nothing.”

Indifference towards Andrés’s illnesses was also observed with other newborns and pregnant women. Flor remembers Daisy, a fellow prisoner and mother of a baby who cried day and night. The baby cried so much that eventually, they only whimpered with closed eyes. “The mother burst into tears when she saw that the child was in critical condition. It was only when their conscience pricked them (the guards) that they took the child out. When they took him to the hospital, we realized that the child was in a coma because his blood was acidic and he had liver problems.”

Although the babies became ill with scabies, flu, fevers, and vomiting, the inmates did not report the precarious conditions because Penitentiary Centers threatened them. “Once, some people came from who knows where (to inspect the prison), and (the prison staff) wanted to cover up the sun with one finger. They didn’t reveal where the scabies-isolated children were. And when visitors came, everything appeared normal. We had to be well-groomed and do everything possible to make it seem like everything was fine. And if someone spoke up, they would threaten them with reports or inform Conapina (National Council for Children and Adolescents) to take their babies away.”

He who owes nothing…

During her pregnancy in the Izalco penitentiary farm, Flor witnessed two fellow prisoners, María Isabel and Carmen, losing their babies due to lack of medical check-ups and treatments. “When we were pregnant, two women gave birth prematurely because when they felt pain, the guards would inject them with diclofenac. They would only do that, and two babies were born prematurely,” she says.

There is no official figure for the number of women detained under the exceptional regime in force since March 27, 2022. Of the 68,720 arrests until May 16, 2023, Socorro Jurídico Humanitario, a human rights organization, estimates that 11,000 are women. “We make this estimate based on data provided by organizations and what we ask released prisoners,” says Ingrid Escobar, a member of that organization. Socorro Jurídico does not have data on how many of these women were pregnant.

“Many of the detained women were pregnant at the time of their arrest and have given birth without their families knowing if their child was born and what the health status of both mother and child is,” states a report prepared by Cristosal during the first year of the exceptional regime. The document provides evidence of women who have suffered induced abortions due to negligence or abuse of authority.

Cristosal cites the testimony of a woman who was imprisoned in the Ilopango prison, known as the Women’s Prison. “Girls who were pregnant and, because they were not given timely medical assistance, had abortions. I saw a girl whose appendix burst in the cell where we were, they took her to the hospital, performed surgery, and three days later they took her back to the floor where we were. Every day, she had to walk up and down all those stairs for treatment, and when they performed the surgery, they didn’t realize she was four months pregnant. After the appendix surgery, the girl’s condition worsened again, and they took her to the hospital, where they realized she was pregnant and performed an abortion.”

Socorro Jurídico Humanitario, Cristosal, and the Movement of Victims of the Regime in El Salvador (MOVIR) have documented the deaths of four women and two newborns in the prison system. The babies died between May and June 2023.

Genesis, a 17-month-old girl, died from bilateral bronchopneumonia at 10:40 a.m. on May 17, 2023.

The girl entered the prison system on August 24, 2022, when her mother, Marbelly Molina, was arrested in a neighborhood in Ahuachapán because an anonymous call accused her of being a gang member. Genesis was eight months old at the time. According to a publication by El Diario de Hoy, the grandmother pleaded with the police to let her keep the baby, but they replied that there were “special places for children and their mothers” in prison.

After multiple requests to Penitentiary Centers, the grandmother regained custody of her granddaughter on April 19, 2023. The baby weighed 19 pounds and was very ill at the Bloom Hospital. The family paid for private treatment and managed to help the child regain a weight of 32 pounds, but a month after leaving prison, she died. Marbelly, the mother, remains detained, unaware that her daughter has died.

Five months after Genesis’s death, on June 26, 2023, Carlos, a six-month-old baby born in the Izalco prison, died.

Penitentiary Centers removed the baby from the prison on June 20, 2023, and when handing him over to his family, the institution claimed he had the flu. The family took the baby to a private hospital in Cojutepeque, where he was diagnosed with pneumonia and scabies. Despite treatments in the public and private healthcare systems, the baby died a week later from acute renal failure, acute hepatic failure, and pneumonia caused by other bacteria. Carlos’s mother, arrested for illicit associations in October 2022, remains in prison, according to MOVIR.

“In front of her, they threw away the medicine”

Flor had gastritis and hemorrhoids before her arrest under the exceptional regime. For that reason, her mother always included medicine to treat those illnesses in the packages, but the medication was never delivered, she says. The package also included items for the baby, but the guards rationed them without any criteria or explanation.

“Once, I saw on the receipt that my mother had sent me 100 diapers, but they only gave me 75 diapers. The worst part is that they think you won’t notice, but you do because sometimes you look at the page. What they (the guards) do is not show you the page, they fold it so you can’t see what they took away. My mother also sent clothes for my baby, and they didn’t give them to me.” Flor had to buy clothes for her baby with her food.

A family can bring a package to their detained relatives once a month. These packages are sold in stores near the prisons and cost between $35 and $175. Depending on the price, the package may include toilet paper, laundry soap, bath soap, toothpaste, antifungal cream, underwear, cookies, nutritional supplements, oatmeal, milk, and coffee. According to Flor and other testimonies obtained by El Faro, Penitentiary Centers do not deliver the packages, and in some cases, only a part of the items is provided.

“The delivery of the packages was at most half. We have the case of a husband who brings his wife 12 rolls of toilet paper, they say they give her 9 out of the 12, and 3 go to ‘the Russians,’ who are active gang members. Many of them don’t receive anything, no one brings them packages,” says Escobar.

According to Socorro Jurídico Humanitario, the most serious issues arise with the medicine that families include in the packages for detainees with serious illnesses. “The delivery of medicine is almost non-existent, that’s what we’ve been told. We see someone with a renal condition, which requires a very specific treatment, and through a peritaje (forensic examination) from the Legal Medicine Institute, they say they need to receive treatment. They (the guards) let them pass, but they tell you, ‘No, go back, we don’t accept it!’ And in front of another person, they throw it away. They tell her there is medicine inside, but that’s a lie. The medical situation is bad throughout the prison system; they attend to people who are practically dying,” Escobar recounts.

Light at the end of Izalco

Andrés had a high fever in May 2023, but he did not receive any medication in the Izalco penitentiary farm. “They only brought down his fever by giving him suppositories,” Flor says. The fever persisted, and the baby was referred to the Jorge Mazzini Hospital in Sonsonate.

On May 24, 2023, a police investigator arrived at the Izalco penitentiary farm to interview Flor and other detainees. After 13 months in prison, the investigator asked two questions in a friendly tone: “Do you belong to a gang? What do your tattoos mean?” “I had to undress so that he could see my tattoos and see that I didn’t have tattoos indicating gang affiliation. He told me that if no new case came up, I would be released soon.”

Five days after the interview, on May 29, 2023, Flor was once again in the Mazzini Hospital, with shackles and handcuffs, in a bed next to her son. That day, Penitentiary Centers gave her a change of clothes and the release letter. Flor needed to return to the Izalco prison because the hospital was an unfamiliar place to her, but the guards told her they couldn’t take her there because it would be considered deprivation of liberty. Flor also couldn’t leave the hospital because she didn’t have her identification card. In the end, another woman took responsibility for her release, bought her food, took her to the Izalco prison, and lent her a phone so she could contact her family through MOVIR.

Flor regained her freedom on May 29, 2023, but she is still disturbed by the mistreatment she witnessed and heard in Izalco. In front of the place where she was confined, she says, there was “a little wall,” and on the other side was the men’s prison. Every night, she would hear screams: “Help, help,” they would shout. Perhaps they were being tortured. The screams were full of terror,” she recalls.

The interview with Flor concluded around eleven-thirty in the morning on June 5, 2023, for two reasons: first, because Andrés woke up from his nap, and second, because Flor had to go to school to pick up her five-year-old son. Andrés no longer cries from itching, but he still has scars from scabies on his little back. He has improved a lot thanks to the care of his mother and grandmother. Flor still has two ongoing legal proceedings, and this is why she granted the interview: “I talk about it because I have experienced these things, and maybe this helps my fellow prisoners to get help or, I don’t know, to help them with their babies. And with the men because they are suffering. And there are many people inside.”

Nacer con régimen de excepción: ‘Las mamás bañaban a los bebés con lejía’

Andrés salió del penal de Izalco el 29 de mayo de 2023 con la espalda llena de granos. La enfermedad que padece se llama escabiosis, conocida como sarna humana, provocada por la humedad y la suciedad. Durante los cinco meses que Andrés estuvo en el penal no recibió ningún medicamento contra la escabiosis ni contra otras enfermedades que padeció durante su encierro.

Andrés, desesperado, lloraba por la picazón. Cuando los granitos rojos se extendían por su espalda y cuello, apenas había cumplido cinco meses de edad.

El recién nacido es inocente con toda la literalidad de esa palabra. Como es obvio, no fue capturado ni procesado por el régimen de excepción, pero fue víctima de la represiva política carcelaria que impidió sus controles médicos antes y después de nacer. Le limitaron los artículos de higiene que su familia le llevaba en los paquetes, y Centros Penales le negó los medicamentos para curar la escabiosis o las fiebres que padeció en la granja penitenciaria de Izalco. Aún hoy, el cuerpo de Andrés muestra las secuelas de aquel padecimiento cuando estuvo en prisión.

Y no fue el único inocente sometido a esos vejámenes. Entre diciembre de 2022 y mayo de 2023, Centros Penales aisló a una treintena de recién nacidos por un contagio de hongos en la granja penitenciaria de Izalco. Así lo cuenta una mujer a la que llamaremos Flor, la madre de Andrés, capturada durante el régimen de excepción por el delito de organizaciones terroristas, pero liberada unos meses después por falta de pruebas.

Ella, según el Estado mismo, no está relacionada con ninguna pandilla ni sus tatuajes son alusivos a esos grupos. Sin embargo, pasó trece meses encarcelada por el régimen de excepción. La Policía la capturó por organizaciones terroristas el 17 de abril de 2022, pero documentos del Juzgado Especializado de Instrucción C2 de San Miguel detallan que fue procesada por agrupaciones ilícitas, sin pruebas contundentes hasta el momento. “Por este medio se le ordena poner inmediatamente en libertad de no existir delito pendiente”, dice un escrito que el juzgado envió al penal de Izalco el 17 de mayo de 2023.

“Eran como unos 30 niños aislados por escabiosis, todos bebés. Aislaron a esos primeros, porque aislaron a un grupo, y supuestamente no les dieron medicamentos, solo los aislaron por aislarlos. Ahí lo que hacían las mamás era a las cremas combinadas que se pasaban le echaban antibióticos, cosas así, para que las ronchitas se le quitaran a los niños. O bañarlos con lejía y Rinso (detergente en polvo) porque no había de otra, no daban medicamentos ellos ahí. Así les tocaba a los pobres niños y sí, se les quitaban las ronchitas”.

—¿Las autoridades sabían que bañaban a los niños con lejía y Rinso? —preguntó El Faro a Flor, el cinco de junio de 2023, durante una entrevista que duró más de una hora y media.

—No, pero era la única medicina, porque como ellos no daban medicamento, a uno no le daban para poder echar en las ronchitas a los niños. Yo nunca bañé a mi niño así (con lejía), porque me daba miedo, pero las mamás que se atrevían… con tal de ver a su niños mejor… porque ellos (Centros Penales) no se preocupaban por darles medicamento.

Flor se rehúso a bañar a su bebé con lejía o detergente en polvo y elaboró su propia medicina. Primero negoció con sus compañeras de prisión pastillas con propiedades antibióticas. Luego, como alquimista, pulverizó las pastillas y las mezcló con sus cremas vaginales. Por último, con agua y sal improvisó una especie de suero con el que bañaba a Andrés todos los días. El bebé mejoró un poco.

Flor aún no entiende por qué su hijo y los otros bebés se contagiaron de escabiosis. Ella describe la prisión como un lugar con suficiente ventilación, con un regular servicio de agua potable y con unos baños limpios. “Lo que tratamos ahí las internas es de mantener bien aseado, pero ni aún… siempre se llenaban los niños de ronchas. Supuestamente nos decían de que era por ácaros que habían en las colchonetas”.

El 17 de agosto de 2021, la Asamblea Legislativa controlada por el presidente Nayib Bukele aprobó la Ley Nacer con Cariño para “garantizar los derechos de la mujer desde el embarazo, así como los derechos de las niñas y niños desde la gestación, durante el nacimiento y la etapa del recién nacido”. Pese a que la ley prioriza el derecho a la salud de la madre y su bebé, para Andrés no hubo control prenatal en el penal. La clínica penitenciaria no dio medicina para curar las enfermedades de la madre y su bebé, y Centros Penales tampoco entregó los medicamentos que su abuela llevaba en los paquetes. “Ahora que salí me doy cuenta que mi mamá me pasaba medicamentos, vitaminas y a mí nunca me dieron nada de eso”, dice Flor.

Andrés no se benefició de la Ley Nacer con Cariño. Él nació en el hospital Jorge Mazzini de Sonsonate y tres días depués fue trasladado a la granja penitenciaria de Izalco. Su bienvenida al mundo fue el régimen de excepción, una política estatal que, según testimonios de presos liberados e informes de derechos humanos, ha normalizado la tortura de reos, en algunos casos hasta la muerte. También son constantes la incomunicación con familiares y abogados, una dieta de hambre y la suspensión de tratamientos médicos y falta de medicina para los privados de libertad que padecen enfermedades.

Desde finales de enero de este año, El Faro ha solicitado en repetidas ocasiones a empleados de Prensa de Centros Penales, Policía, Fiscalía y Ministerio de Seguridad, que gestionen una entrevista con los responsables de esas instituciones o con algún vocero designado. Se ha intentado por medio de cartas que se han dejado en esas oficinas, correos electrónicos, mensajes de WhatsApp y llamadas telefónicas. No se ha concedido ni un espacio para hablar de las detenciones arbitrarias del régimen. Esto no solo ocurre con el área de seguridad del Gobierno, sino que es ya un patrón en cualquier institución pública ante las solicitudes de este medio.

“Antecedentes, ese fue mi delito”

El 19 de mayo de 2019, la Policía capturó a un hombre que transportaba diez paquetes de marihuana y una porción de cocaína en el baúl de un carro. Al detenido lo acompañaba Flor, procesada y condenada a trabajos de utilidad pública por el hecho.

El 17 de abril de 2022, ella estaba en su casa bajo libertad condicional, trabajaba junto a su madre en un negocio de venta de jugos y estaba a la espera de que el sistema judicial le dijera en qué institución iba a cumplir con el trabajo de utilidad pública. Sin embargo, a las dos de la tarde de ese día, cuando se alistaba para ir a comprar naranjas con su madre a San Miguel, la Policía llegó a su casa y la llevó a un puesto policial.

“Me dijo que los iba a acompañar y le pregunté: ‘¿por qué?’ Él dijo que no sabía. Les pregunté si andaba orden de captura y dijo que no, que solo los iba acompañar. En la delegación, me dijo que me detenían por agrupaciones terroristas. ‘¿Por qué?’, le dije, ‘yo nunca he matado a nadie’. Cuando fui a la Procuraduría, el licenciado me dijo que a toda la gente la estaban capturando por tener antecedentes penales”.

El artículo 11 de la Constitución de la República establece que nadie “puede ser enjuiciado dos veces por la misma causa”. La Policía ha violado esta disposición constitucional y ha utilizado casos juzgados en el pasado para realizar detenciones durante el régimen de excepción. Este es el caso de Flor, quien esperaba la orden judicial para cumplir una condena. El Faro también ha documentado casos donde el delito de los detenidos fue haber sido declarados inocentes en el pasado, como en el caso de Don Paco, un comerciante de La Reina, en Chalatenango, quien murió en Mariona con señales de una golpiza.

Luego de su captura, Flor fue trasladada a la bartolina de Osicala. Al siguiente día, el 18 de abril, la llevaron al penal de Ilopango y así inició para ella un proceso judicial surrealista. “La Fiscalía dijo que no podía decirnos el delito de cada uno, por la cantidad que éramos, pero de que a todos nos acusaba de agrupaciones ilícitas. Éramos como unas 50 personas, personas que yo ni conocía”. Diversas organizaciones humanitarias han denunciado procedimientos judiciales masivos durante el régimen, donde los jueces envían a prisión a decenas e incluso cientos de acusados tras una breve audiencia donde no se presenta ninguna prueba que individualice las participaciones en los supuestos delitos.

En el penal de Ilopango, Flor compartió celda con 300 mujeres más. La celda estaba saturada, por lo que en un catre sin colchón dormían cinco personas. Durante las noches, el piso de la celda estaba tan lleno de personas que no se podía caminar. Aquella multitud de detenidas también sufría por la escasez de agua potable: “solo nos daban dos guacaladas de agua para bañarnos”. Entre tanto hacinamiento y penuria, pasó un día, una semana, un mes… cuando ya sumaba un mes y medio de encierro en Ilopango, Flor se enteró de que estaba embarazada.

Los maltratos en Izalco

Flor tenía siete semanas de gestación cuando fue trasladada junto a otras 11 embarazadas más del penal de Ilopango a la granja penitenciaria de Izalco. Al llegar ahí, las custodias le quitaron las pocas cosas que llevaba: una pijama, una cobija, un vaso, una comidera y un uniforme penitenciario. Las custodias tiraron todo eso a la basura.

En la granja penitenciaria de Izalco están recluidas las privadas de libertad que son madres o que están cerca del parto. Aunque ellas necesitan una atención médica y alimentación especial para garantizar la buena salud de sus bebés, en ese lugar son sometidas a maltratos, tal como lo vivió y lo cuenta Flor.

“Las custodias eran bien repugnantes. A todas las embarazadas nos trataban bien feo. Nos sacaban al sol, en el puro sol de las 12 del mediodía. Nos ponían a jalar agua estando embarazadas. Llegaban unas pipas (a la granja penitenciaria de Izalco), porque a veces no llegaba el agua, entonces nos tocaba jalar el agua. Nos tocaba salir a tender ropa de todas las que habíamos en la celda. Habíamos como unas 150 embarazadas”.

Flor identifica a dos custodios como los protagonistas de aquellos maltratos: una custodio a la que conocían con el alias de “Sirena” y un jefe penitenciario al que llamaban “el jefe Shangai”. “El grupo de Sirena era el que nos trataba así y nos sacaban al puro sol. Las demás (custodias) nos consideraban, nos dejaban cinco minutos en el sol y de ahí dejaban que nos sentáramos en la sombra, pero cuando estaba el turno de Sirena todo el rato teníamos que estar en el puro sol. Una vez me sentía bien débil, solo miraba el bulto blanco de mis compañeras, miraba bien borroso”, recuerda.

El jefe Shangai, por su parte, trataba de imponer respeto por medio del maltrato físico y verbal. “A veces llegaba a decirnos que parecíamos prostitutas de la avenida, decía que teníamos que respetarlo como que él era un dios. Teníamos que saludarlo y, si no, nos insultaba, nos iba a poner a pagar (castigar): hacer sentadillas estando así, una embarazada. Yo vi a una embarazada hacer sentadillas. La ilusión de nosotras era que se dieran cuenta (organizaciones de defensa de) los derechos humanos”.

Flor estuvo en el dormitorio uno, sector materno de la granja penitenciaria de Izalco. La granja tiene una clínica que es atendida por dos doctoras. Una de las doctoras, la doctora Córdova, atendió a Flor durante la primera consulta que recibió después de su traslado, a mediados de junio de 2023. De la primera consulta, Flor recuerda que recibió unas pastillas prenatales, hierro y antibióticos, pero se percató de que esos medicamentos estaban vencidos. En los siguientes meses de embarazo, no tuvo ningún control médico.

Las dos doctoras atendían a las 150 embarazadas, a las mujeres que ya habían parido y sus bebés, y a las privadas de libertad en fase de confianza, en su mayoría de la tercera edad. Las dos doctoras no daban abasto.

Un día, durante el octavo mes de embarazo, Flor sintió un terrible dolor en el estómago. La doctora Córdova le dio dos pastillas de omeprazol y la regresó al dormitorio. “Le dije a la doctora que no aguantaba el dolor de la gastritis y ella me dijo: ¿Y qué querés que haga? ¿Que salga afuera, te compre una inyección y te la ponga? Medicamentos aquí no hay, me dijo”.

Las dos pastillas de omeprazol no hicieron ningún efecto y el dolor se agudizó por la noche. La doctora de turno la revisó de nuevo y la remitió al hospital Jorge Mazzini de Sonsonate, donde le diagnosticaron cálculos en la vesícula. Flor necesitaba una cirugía, pero por su estado de embarazo eso no era posible en ese momento. Entonces, un nutricionista le recetó una dieta. “Yo le dije que la dieta no me la iban a dar ahí (en el penal), que era mentira. Una doctora me dijo: ‘¡Ay Dios, hija, solo con dolor va pasar aquí! Usted necesita dieta’, me dijo. Y cuando llegué al penal, cabal, no me dieron la dieta”.

Un mes después de aquellos insoportables dolores, el 25 de diciembre de 2022, nació Andrés. Era un niño desnutrido, se miraba como “amarillito”, dice su madre. El niño quedó ingresado durante tres días, pero su madre, por protocolo de seguridad, regresó de inmediato al penal de Izalco después del parto. Andrés estuvo los primeros tres días de su vida en el hospital Mazzini sin la compañía de su mamá, pese a que la Ley Nacer con Cariño establece que uno de los derechos del niño es el “apego seguro inmediato, mediante el contacto piel a piel inmediatamente después del nacimiento que le permita amamantarlo y cargarlo”.

Tres días después de su nacimiento, Andrés ingresó a la granja penitenciaria de Izalco y tuvo dos controles médicos en el que le aplicaron unas vacunas: el primero a los siete días y el segundo a los 40 días de nacido. Después de eso ya no hubo ningún control o revisión médica para el bebé.

Antes de contagiarse de escabiosis, Andrés padeció gripe y tampoco recibió atención médica, dice su madre. “Le dije a la doctora Córdova que el niño estaba mal, que si me podía regalar una perilla para sacarle los moquitos al niño. ‘¡Yo, perillas no tengo!’, me dijo. y me gritó bien feo, se dio la vuelta y no me dio nada”.

La indiferencia ante las enfermedades de Andrés se repetía con otros recién nacidos y otras embarazadas. Flor recuerda a Daisy, una compañera de prisión, madre de un bebé que lloraba de día y de noche. El bebé lloró tanto que, al final, solo gemía con los ojos cerrados. “La mamá se soltó en llanto al ver que el niño estaba en las últimas. Hasta que les remordió la conciencia (a las custodias) sacaron al niño. Cuando lo llevaron al hospital nos dimos cuenta que el niño estaba en coma porque tenía ácida la sangre y problemas en el hígado”.

Aunque los bebés se enfermaban de escabiosis, gripe, fiebres y vómitos, las privadas de libertad no denunciaban las condiciones precarias porque Centros Penales las amenazaba. “Una vez, llegaron unas que no sé de qué país habían venido y (los del penal) querían tapar el sol con un dedo. Y no, no habían dicho dónde estaban los niños aislados por escabiosis. Y ahí, cuando llegaba una visita, todo era normal. Teníamos que estar bien bañadas y hacer todo lo posible, como hacer pasar de que todo estaba bien. Y si alguien hablaba, lo amenazaban con reportes o que iban a hablar al Conapina para que le quitaran a los bebés”.

El que nada debe…

Durante su embarazo en la granja penitenciaria de Izalco, Flor atestiguó que dos compañeras de prisión, María Isabel y Carmen, perdieron a sus bebés por falta de controles y tratamientos médicos. “Cuando estábamos embarazadas a dos se les vinieron los bebés porque cuando sentían dolor lo que hacían era inyectarles diclofenac. Solo eso hacían, y se les vinieron (los bebés) a dos”, dice.

No existe una cifra oficial de mujeres detenidas por el régimen de excepción que está en vigor desde el 27 de marzo de 2022. De las 68,720 capturadas hasta el 16 de mayo de 2023, Socorro Jurídico Humanitario, una organización de derechos humanos, estima que 11,000 son mujeres. “El cálculo lo hacemos de acuerdo a las organizaciones que nos dan datos y lo que preguntamos a las liberadas”, dice Ingrid Escobar, parte de esa organización. Socorro Jurídico no tiene datos de cuántas de esas mujeres estaban embarazadas.

“Muchas de las mujeres detenidas estaban embarazadas al momento de la detención y han dado a luz sin que sus familias sepan si su hijo o hija nació y cuál es el estado de salud de ambos”, consigna el informe que Cristosal elaboró durante el primer año de aplicación del régimen de excepción. El documento aporta indicios sobre mujeres que han sido víctimas de abortos provocados por negligencia o abuso de autoridad.

Cristosal cita el testimonio de una mujer que estuvo presa en el penal de Ilopango, conocido como Cárcel de Mujeres. “Muchachas que iban embarazadas y, como no se les dio asistencia médica a tiempo, pues abortaron. Yo vi a una muchacha que a ella se le reventó su apéndice en la celda donde estábamos, la llevaron al hospital, le hicieron el lavado y a los tres días la llevaron nuevamente al piso dónde estábamos. Todos los días tenía que salir caminando ella por todas esas gradas para ir a curación, y cuando le hicieron la cirugía no se dieron cuenta que la muchacha tenía cuatro meses de embarazo y después que la habían operado del apéndice, la muchacha se agrava nuevamente, la llevan al hospital y se dan cuenta que ella estaba embarazada y le hicieron un legrado”.

Socorro Jurídico Humanitario, Cristosal y el Movimiento de Víctimas del Régimen en El Salvador (MOVIR) han documentado la muerte de cuatro mujeres y dos recién nacidos en el sistema penitenciario. Los bebés fallecieron entre mayo y junio de 2023.

Génesis, una niña de 17 meses de edad, falleció por bronconeumonía bilateral a las 10:40 de la mañana del 17 de mayo de 2023.

La niña ingresó al sistema penitenciario el 24 de agosto de 2022, cuando su madre Marbelly Molina fue arrestada en una colonia de Ahuachapán porque una llamada anónima la acusó de ser pandillera. Génesis tenía ocho meses de edad. Según una publicación de El Diario de Hoy, la abuela suplicó a los policías que le dejaran a la bebé, pero ellos replicaron que en la cárcel “había lugares especiales para los niños y sus madres”.

Tras múltiples peticiones a Centros Penales, la abuela recuperó la custodia de su nieta el 19 de abril de 2023. La bebé pesaba 19 libras y estaba muy enferma en el Hospital Bloom. La familia pagó un tratamiento privado y logró que la niña recuperara las 32 libras de peso, pero un mes después de salir de prisión falleció. Marbelly, la madre, continúa detenida, sin saber que su hija murió.

Cinco meses después de la muerte de Génesis, el 26 de junio de 2023 murió Carlos, un bebé de seis meses que nació en el penal de Izalco.

Centros Penales sacó al bebé del penal el 20 de junio de 2023 y, al entregarlo a su familia, la institución argumentó que padecía gripe. La familia llevó al bebé a un hospital privado de Cojutepeque, donde le diagnosticaron neumonía y escabiosis. Una semana después, pese a tratamientos en el sistema de salud público y privado, el bebé murió por insuficiencia renal aguda, insuficiencia hepática aguda y neumonía debido a otras bacterias. La madre de Carlos, capturada por agrupaciones ilícitas en octubre de 2022, continúa en prisión, según MOVIR.

“Frente a ella le botaron la medicina”

Flor padecía de gastritis y hemorroides desde antes de su captura por el régimen de excepción. Por esa razón, su madre siempre incluía medicina para tratar esas enfermedades en los paquetes, pero el medicamento nunca le fue entregado, según dice. El paquete también incluía cosas para el bebé, pero las mismas eran racionadas por las custodios sin ningún criterio y sin ninguna explicación.

“Una vez vi en la papeleta de que mi mamá me había pasado 100 pampers y a mí solo me entregaron 75 pampers. Lo peor del caso es que según ellos uno no se va a dar cuenta, pero uno se da cuenta porque a veces se fija en la página. Lo que hacen ellos (custodios) es que no le muestran la página a uno sino que la doblan para que uno no vea lo que le han quitado. Mi mamá también le pasó ropa a mi niño y no me la dieron”. Flor tuvo que comprar, con su comida, ropa para su bebé.

Una familia puede llevar a sus detenidos un paquete una vez al mes. Esos paquetes los venden en tiendas que están en los alrededores de los penales y su precio oscila entre los 35 y 175 dólares. Según el precio, el paquete puede incluir papel higiénico, jabón para lavar ropa, jabón de baño, pasta de dientes, crema combinada contra los hongos, ropa interior, galletas, ensure, avena, leche y café. Según Flor y otros testimonios obtenidos por El Faro, Centros Penales no entrega los paquetes y, en algunos casos, entrega solo una parte de los artículos.

“El paso de los paquetes era si acaso la mitad. Tenemos el caso de un esposo que le lleva a su esposa 12 rollos de papel higiénico, dicen que le están dando 9 de los 12, y 3 van para ‘las rusas’, que son pandilleras activas, muchas de ellas nadie les entra nada, nadie les lleva paquete”, cuenta Escobar.

Según Socorro Jurídico Humanitario, lo más grave sucede con la medicina que las familias ponen en los paquetes para detenidos con enfermedades graves. “Medicina es casi nula la entrega, eso sí nos lo han dicho. Vemos que alguien tiene un padecimiento renal, que es un tratamiento bien específico, y vía peritaje (de Medicina Legal) dicen que hay que darle tratamiento. Ellos (custodios) los pasan, pero a uno le dicen: ¡no, regrese, no lo aceptamos! Y a otra ahí enfrente de ella se lo han botado. Le han dicho que no, que adentro hay medicina, pero eso es mentira. En la medicina estamos mal en todo el sistema penitenciario, atienden a la gente que de plano ya está para morirse”, relata Escobar.

Luz al final de Izalco

Andrés padeció una fuerte fiebre en mayo de 2023, pero en la granja penitenciaria de Izalco no le dieron medicina. “Solo me lo bajaron para ponerle supositorios”, cuenta Flor. La fiebre siguió y el bebé fue remitido al hospital Jorge Mazzini de Sonsonate.

El 24 de mayo de 2023, un investigador de la Policía llegó a la granja penitenciaria de Izalco para entrevistar a Flor y a otras detenidas. Después de 13 meses en prisión, el investigador hizo dos preguntas en tono amable: ¿Pertenece a una pandilla? ¿Qué significado tienen los tatuajes? “Me tuve que desnudar para que él viera los tatuajes y que no andaba tatuajes de que pertenecía a pandilla. Que si no me salía otro caso ya iba a salir libre, me dijo”.

Cinco días después de la entrevista, el 29 de mayo de 2023, Flor estaba otra vez en el hospital Mazzini, con grilletes y esposas, en una cama al lado de su hijo. Ese día, Centros Penales le dio una mudada de ropa y la carta de libertad. Flor necesitaba regresar al penal de Izalco porque el hospital era un lugar desconocido para ella, pero las custodias le dijeron que no podían llevarla porque cometerían el delito de privación de libertad. Flor tampoco podía abandonar el hospital porque no tenía DUI. Al final, una muchacha se hizo responsable de su salida, le compró comida, la llevó al penal de Izalco y le prestó el teléfono para que pudiera contactar a su familia por medio del MOVIR.

Flor recuperó su libertad el 29 de mayo de 2023, pero aún le perturban los maltratos que vio y escuchó en Izalco. Frente al lugar donde estuvo recluida, dice, había “un murito”, y al otro lado estaba el penal de los hombres. Todos los días, por las noches, escuchaba gritos: “‘Auxilio, ayúdenme’, decían ellos gritando. Quizás los estaban torturando. Se oía que sí los estaban torturando porque los gritos que daban eran unos gritos de terror”.

La entrevista con Flor concluyó casi a las once y media de la mañana del cinco de junio de 2023 por dos razones: primero, porque Andrés despertó de su siesta; y, segundo, porque Flor debía ir al colegio por su hijo mayor, de cinco años. Andrés ya no llora por la picazón, pero aún tiene marcas de la escabiosis en su pequeña espalda. Ha mejorado mucho gracias a los cuidados de su madre y de su abuela. Flor aún tiene dos procesos judiciales abiertos y así explica por qué concedió la entrevista: “Lo hablo porque yo ya pasé por estas cosas y tal vez esto ayuda para que les ayuden a mis compañeras a salir. O, no sé, para que les ayuden con los bebés. Y con los hombres porque están sufriendo. Y hay muchas personas allá adentro”.