Angelica says she already had a feeling, but it was that video that confirmed her suspicions.

It had been shared in a Facebook group and he went through it patiently, frame by frame.

After 25 minutes, when he saw the man sitting cross-legged shaking hands with his bunkmate, he stopped him in his tracks. He stepped back and let it go for a few seconds before pressing stop again.

Although his head was shaved and he was dressed, like the rest of the prisoners, only in white underwear, she had no doubts: it was her husband, Darwin.

I had not seen him since his arrest on March 30, 2022, 11 months ago.

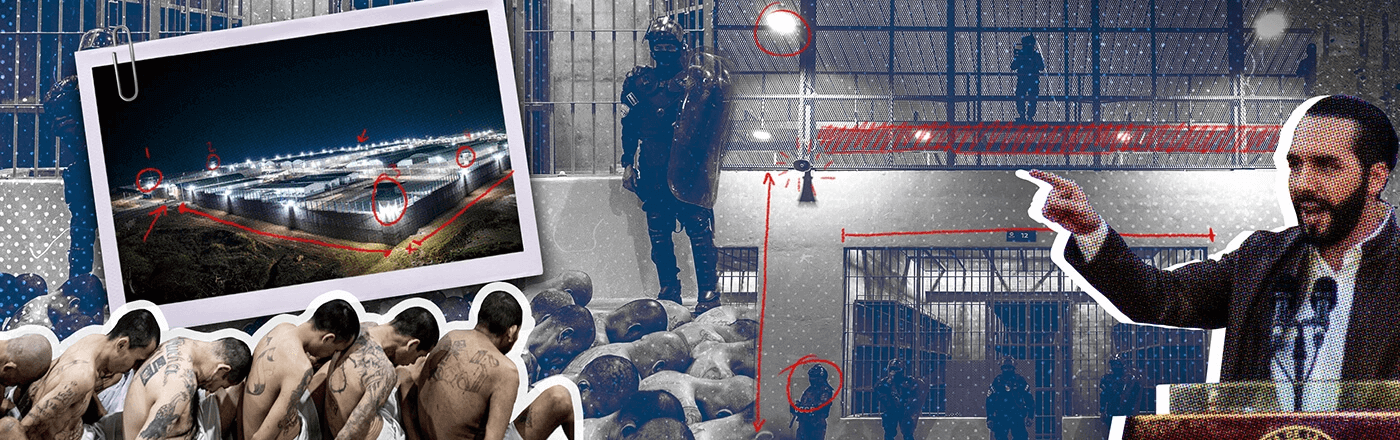

These images were the first evidence that he had been transferred to the Terrorism Confinement Center (Cecot), the mega-prison inaugurated by President Nayib Bukele on January 31, 2023, which has become a symbol of his “war against gangs” and of the security policy that has given him unprecedented popularity nationally and internationally.

Support for Bukele is based primarily on the drastic reduction in homicides that has been registered since his government began in what was once the most violent country in the world.

There are many who highlight this change and breathe a sigh of relief, especially in neighborhoods formerly controlled by gangs, where “see, hear and shut up” was the rule, and neighbors can now cross the invisible borders that gangs historically imposed without suffering harassment and without fear of reprisals.

However, five months after its inauguration, the Cecot is also an exponent of the secrecy and accusations of opacity of the emergency regime approved after 76 murders in just 48 hours in March 2022.

Since it began, nearly 70,000 people have been detained, a number of guarantees are suspended and there are numerous reports of serious human rights abuses, from arbitrary arrests and torture to deaths in state custody.

There are thousands of Salvadorans who have not heard from their detained relatives for months and who, like Angélica, search for them in videos, photographs, or by peeking through small holes in the walls of the prisons they manage to get close to.

The Cecot was presented to Salvadorans on national radio and television as “the largest prison in all of the Americas”.

It has, according to the government, a capacity for 40,000 prisoners, and is exclusively for those “profiled as high ranks” of the Mara Salvatrucha (or MS-13) and the two factions of the Barrio 18, rival gangs that have been increasing their power for decades by recruiting youths and controlling territories, and sowing terror, division and death in the Central American nation.

After appearing in the media touring its facilities, Bukele highlighted it on Twitter, his favorite platform to promote the results of his administration:

“El Salvador has managed to go from being the most insecure country in the world to the safest country in the Americas”.

“How do we do it? By putting the criminals in jail. Is there room? Now there is. Will they be able to give orders from inside? No. Will they be able to escape? No. A work of common sense,” he added.

With similar media hype, the entry of 2,000 inmates into the prison was announced on February 24 and on March 15, the only two transfers of which there is public knowledge to date.

It was among those official images of half-naked men at times running crouched, at times sitting close together, that Angelica identified her husband, a Honduran man who had been deported from the U.S. in 2018 after serving a sentence for robbery and who subsequently emigrated to El Salvador, where he has no criminal record.

“I recognized him by the tattoos,” the same ones that, he tells BBC Mundo, led to his arrest for “illicit groupings,” a crime that in El Salvador covers not only those who lead or participate in gangs but those who “indirectly profit” from relations with them, whatever their nature.

It is because of this recording – and because she has a receipt proving that she deposited US$90 for her husband’s prison expenses with the General Directorate of Penal Centers – that she is convinced that her husband spends his days in one of the 256 cells of the giant prison.

After the controversial opening, but before the prisoner transfers, several media outlets entered the Cecot, but public information about the conditions in which the prisoners live there is scarce, if not non-existent.

BBC Mundo received a refusal to its request to visit her. And as of the time of publication of this report, the requested interview with President Bukele or another representative of the Executive to discuss the questions raised in recent months is still “pending”.

But from videos (from the government and the press), photographs, interviews with authorities and data contrasted by a technician involved in the construction, whose identity we do not reveal for security reasons, we have recreated details of the mega-prison to try to give a greater context of its dimension.

The square meters that each prisoner would have is precisely one of the questions that BBC Mundo has not been able to answer.

According to what Héctor Saldaña, an engineer from El Salvador’s prison facilities, stated in an interview with the Colombian magazine Semana, “we comply with international standards at the Latin American level (…) We comply with more than 2.5 square meters per prisoner”.

But plans seen by BBC Mundo indicate that each cell measures 7.4 by 12.30 meters, or 91.02 square meters, which translates into just 0.58 square meters per person.

The International Committee of the Red Cross recommends 3.4 square meters per prisoner in a group cell, according to the latest edition of its guide on water, sanitation, hygiene and habitat in prisons.

These recommendations are addressed to authorities around the world, although the Red Cross holds private, unilateral discussions with governments and these exchanges, as well as any specific recommendations, are confidential.

This is especially relevant if one takes into account that although official videos have shown a factory where the prisoners would eventually work, the authorities themselves have explained that the cells are designed so that the prisoners spend as much time as possible there, and only leave to go to the courtroom by videoconference or to solitary confinement.

In the common cells, natural light comes from the skylights, louvers and curved ceilings of the pavilions, which are also the only source of ventilation in a country where the temperature can exceed 30 degrees Celsius, with a relative humidity of 60%.

In the punishment cell there is only a cement slab that serves as a bed, a water basin, and a toilet.

The Vice Minister of Justice and General Director of Penitentiary Centers, Osiris Luna, pointed out in a promotional video that the prisoner who is taken there will be handcuffed and will remain almost in the dark, except for a small round hole in the ceiling.

To date, it is not known if there are any inmates living in these conditions.

In the Cecot “no yards have been built, no recreation areas have been built for the inmates”, informed at the time the Minister of Public Works, Edgar Romeo Rodríguez Herrera, which contravenes the Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, approved in 2005 by the General Assembly of the United Nations (UN).

Also called the Nelson Mandela Rules in honor of the former South African president – perhaps the best-known prisoner of the 20th century – these rules provide states with guidelines for protecting the rights of persons deprived of their liberty.

They state, among other things, that “every prisoner shall have at least one hour a day of adequate exercise in the open air” (Rule 23).

In the new prison complex there are also no conjugal spaces, unlike other penitentiaries. “There are no intimate visits or family visits. That is prohibited for this type of person,” said Vice Minister Luna during the televised tour in which he accompanied Bukele.

These official descriptions raise concerns among experts.

“Not having communication with the family extends their punishment to innocent people,” Miguel Sarre, a former member of the United Nations Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and someone with extensive experience overseeing prison systems, tells BBC Mundo.

- It is not known exactly how many prisoners there are, if only the 4,000 that were seen in the videos of the two transfers or if there were other transfers that were not broadcast.

- The criteria for transfers to Cecot are not public and there are doubts about the identity of those who are imprisoned there, whether they were detained during the emergency regime or are gang members who were serving sentences in other prisons.

- No details are known about the feeding routines; when, where and what the inmates eat. Nor if there is a kitchen, dining room, infirmary or store in the facilities.

- What is known is that the government acquired 166 hectares in the vicinity of Tecoluca, a municipality in the central department of San Vicente, to build it.

- It is located about 74 kilometers southeast of the capital, San Salvador, in a rural setting where a few communities live and work mainly in corn and bean plantations.

- The prison was built in less than a year.

- Experts estimate that it would otherwise take three years.

Information on the bidding and awarding processes for the works, as well as construction and operating costs, was declared confidential by the government.

A series of laws passed by the Legislative Assembly -controlled by the ruling party- allows for the acceleration of such processes and reduces controls over them.

The Minister of Justice and Public Security, Gustavo Villatoro, explained in an interview with Americano Media in February that it was possible to build it in 7 months “thanks to uniting the largest builders in the country and putting them to work to generate this in such a short time (…) Many construction projects, urban development or apartment towers in the country ran out of labor and at some point in the construction we even ran out of cement at the national level, because everything was being absorbed by the construction of this mega penal center”.

That same month, shortly after Cecot’s inauguration, the BBC had the opportunity to speak with him.

“For us, it represents the greatest monument to Justice that we have ever built. There is nothing to hide,” he said in that interview.

“The members of these terrorist organizations will go there. This is not a place for the detention of social base, of collaborators. The collaborators will be in other prisons, where they will have rehabilitation programs, to be able to work. Cecot, those who go there, we have a commitment with the Salvadorans that they will never return, that they will not return to the communities. And we are going to take care of building the necessary cases so that they do not return.

Gustavo Villatoro, Minister of Justice and Public Security

Four months after these statements, we returned to El Salvador and traveled to the vicinity of the prison.

We stop to buy water at a food and beverage store, the only one for miles around, strategically located at the intersection of the main road to Tecoluca and the street leading to Cecot.

In the early hours of the morning – and that in El Salvador is six o’clock in the morning – there are already half a dozen prison guards and police and military personnel from the surrounding checkpoints, drinking coffee.

From one of its plastic tables we can see, about 500 meters away, one of those checkpoints to access the prison facilities, which only authorized personnel can cross.

Sitting next to us, a policeman with dark glasses sucks on his cup and confirms that since January, security personnel in the area have been increased.

“Not even El Chapo (Guzmán, known for his notorious escapes from maximum security prisons) could escape from there,” he says, echoing the government’s discourse on the pharaonic project.

A little before noon, when eight women can’t keep up with filling the pile of polystyrene containers with the roasted chicken, rice and two tortillas that will serve as lunch for the Cecot staff, we will take the unpaved road that leads to the Buen Amanecer community.

And from this area of tin houses and dirt floors, to which its inhabitants moved about two years ago because they were given the land but not the deeds, we will distinguish among the trees and under the imposing Chichontepec volcano a couple of watchtowers of the mega-prison and the brightness of the vaulted roof of the pavilions.

It is impossible to get any closer.

- The penitentiary complex has 23 hectares of buildings.

- It has 8 pavilions or modules of 5,446 square meters with 32 cells each.

- Two perimeter security fences with cyclone mesh, fully electrified, and two reinforced concrete walls surround the facilities. There are 19 guard towers.

- Minister Villatoro emphasized that the facilities and the prisoners will be guarded by 1,000 guards and 250 members of the National Civil Police (PNC)…

- …and 600 members of the Armed Forces will be in charge of guarding the outer ring.

His break over and before heading back to his post, the sunglasses-wearing policeman admits that his life has improved considerably in recent months.

“Before, I had to go and take the gang members to their homes, with all that that entailed. Now I spend the day at the checkpoints and every once in a while I have time to have a coffee.”

Police

Her mood contrasts with that of Maria, 23, whom we met not far from there, at her home in El Maniadero, another of the surrounding communities.

His mother is not here. Since her partner, who paradoxically worked for six months in the construction of the prison, was arrested for “illicit groupings”, she usually goes to the market to make and sell tortillas from Monday to Friday.

“I go on weekends,” the young woman tells us, sitting by the fire on which she will later prepare the meal and which raises the sticky midday heat to maximum power.

“The rest of the time I spend at home or at my aunt’s.”

She doesn’t risk going out, she says, for fear that what happened to her stepfather or her friend Jessica, who was taken away by the police under emergency rule, leaving behind a 3-year-old girl, will happen to her.

“It seems that being young is now a crime in El Salvador.”

Maria

The arrests are -along with rumors that the water runs dirty in the creek since the construction of the Cecot and that at some point they will be evicted because they are going to build a women’s prison in the area- a recurring conversation among the neighbors of the neighborhoods built on what used to be the railroad track.

68,294 people have been arrested since the emergency regime began, according to the most recent figures from the Ministry of Security as of May 4.

And although the Cecot is the most symbolic prison, the majority of those arrested are not there, but in some other prison in preventive detention. Some have been there for months, even more than a year.

Even before these arrests, El Salvador topped the global statistics of the most incarcerating countries and its prison system suffered from chronic overcrowding.

So much so, that in 2016 the Salvadoran Supreme Court declared the situation of overcrowding in prisons unconstitutional, stating that it violated “the fundamental right to personal integrity.”

In an effort to alleviate overcrowding, nine facilities were opened between April 2015 and March 2019, increasing the capacity of the prison system by 16,296 places.

But it was like putting Band-Aids on an arterial hemorrhage.

“Here they come in healthy and leave sick,” says a policeman who speaks through gritted teeth as he stands guard at the entrance to the La Esperanza Penal Center, better known as “Mariona”.

We have come to ask when we hear that a man is coming to pick up an inmate who had to have his foot cut off due to a complication resulting from his diabetes and who is going to be released that same afternoon.

The Cecot is the first prison built under Bukele’s government, and he has insisted that it has the state-of-the-art technology of a “first world” prison at its service, with scanning systems at the entrance to detect any illegal objects that detainees try to introduce and a vast surveillance and control network, including a weapons room with a large arsenal.

But not everyone shares his vision.

“Although it has some more advanced elements, it is not modern,” counters Abraham Abrego, litigation director of Cristosal, the leading civil society human rights organization in El Salvador.

“It is not new in terms of reinsertion or rehabilitation mechanisms. It is basically a punishment mechanism, merely punitive, and that is a medieval logic, not a modern exercise,” he says.

Abraham Abrego

Antonio Durán, second sentencing judge of Zacatecoluca and one of the few magistrates openly critical of the Bukele administration and its regime of exception, agrees and goes further.

“In a state governed by the rule of law, deprivation of liberty is the punishment. You punish the offender by depriving him of his freedom,” he tells BBC Mundo.

“But here it is understood that he is deprived of liberty to be punished inside the prison. And that is not only wrong but also criminal. It is torture.”

“If you don’t go after your family member, he or she may die and you don’t know about it.

Angeles believes that her brother is in the Cecot because she recognized him, like Angelica recognized her husband, in the images of one of the transfers of prisoners to the mega-prison.

“I opened my Facebook and there I saw him, all beaten up, almost naked, in his boxer shorts, and I got really upset,” she says sitting in her home in Santa Ana, some 70 kilometers west of the capital.

She is exhausted after spending the day buying merchandise for informal sales.

Retired from the gang in 1995, the woman says, her brother had been running a small store in the same neighborhood for years when, on April 13, 2022, several agents arrived at his house and took him to the police station.

She never heard from him again. Until she identified him on the social network.

Glenda and Heidy are convinced that their brother and husband, respectively, met the same fate. They were also arrested in April 2022, and taken first to the police station, then to the Izalco prison.

They have not identified them in any video, but believe they have obtained other corroboration that they are in the Cecot.

“I called and called and one of the guards confirmed it to me. And I also sent someone to verify if it was true that he had been moved. I was left with my mouth open when they told me,” says Glenda.

Tracking them down has been particularly difficult for these women living in the United States. “But if you don’t go after your imprisoned relative, they may die and you won’t know about it,” continues Glenda, who refuses to give up.

“Those are the only avenues of information, the informal ones . There is no formal notification of the transfer in any of the cases.”

Ricardo Bolaños, lawyer and activist who collaborates with the Movement of Victims of the Regime (Movir).

BBC Mundo spoke with dozens of relatives of those imprisoned under the emergency regime and the story is repeated.

Many, mostly men, have been taken from their homes without being shown a search or arrest warrant, taken to a virtual hearing along with dozens of other detainees, and the judge has ordered them remanded in custody while the Prosecutor’s Office investigates whether there is evidence for a formal indictment.

Following a series of legal reforms, this investigation phase can now take months, even years.

“At first, people believed that their family member would return after 15 days. Then after six months. After the arrest, the ordeal begins for the families: they go to the nearest police station, to the first prison, to the second, to the Attorney General’s Office…”, explains Zaira Navas, former inspector general of the Police and current coordinator of Cristosal in the analysis of the emergency regime.

“In addition, there is no centralized registry where the family can come and say: ‘My son was detained in the department of Usulután and I want to know which prison he is in,” he continues.

BBC Mundo was able to witness this anguished search when it visited different prisons and spoke with Salvadorans who come to the same doors every week to ask for their detained relatives, wait seated for hours as in the Apanteos prison, or look through the holes in the outer wall every time there is a transfer of prisoners, as in the Ilopango prison.

Navas heads a team investigating hundreds of complaints of possible human rights violations during the emergency period.

The report presented on May 29, which was based on an exhaustive investigation and which went around the world, concludes that in the first year of these measures, dozens of inmates have died from torture, beatings or lack of health care in the country’s prisons.

The government has not publicly responded to the report. But Human Rights Commissioner Andres Guzman Caballero, who took office on May 24, acknowledged after being questioned during an event in which he was participating by the Salvadoran media La Prensa Grafica that the report is “worrisome”.

“We close May 10, 2023 with 0 homicides nationwide. With this, that’s 365 days without homicides, a whole year,” Bukele announced on Twitter during that day.

Five days passed and a dead policeman broke the statistic.

“The gang members still left in our country have just assassinated one of our heroes” , the Salvadoran president tweeted at the time.

“But the ‘human rights’ NGOs will say nothing, they only watch over the rights of criminals. Do you see why we must continue with the regime of exception until this plague is completely over? This cowardly murder will not go unpunished. We will make them pay dearly for what they did”. he continued.

And a few hours later he insisted: “Let all the ‘human rights’ NGOs know that we are going to raze these damned murderers and their collaborators to the ground, we will put them in prison and they will never get out”.

That combination of tweets is a good reflection of the security policy promoted by Bukele, who heads the Salvadoran Executive since July 2019.

His is not the first government in El Salvador with “mano dura” (iron fist) strategies, but with his frontal war he has managed to dismantle the gangs, as proclaimed by officials and recognized by experts and organizations on the ground.

The gangs “had territory, population, they dispensed justice, with weapons, but they dispensed justice, they had revenue… We are definitely fighting against a parallel state, and that parallel state, for the good of the more than 6 million Salvadorans, is destroyed,” Security Minister Gustavo Villatoro told the BBC in an interview earlier this year.

This is evident on the streets, as BBC Mundo was able to verify on two visits to the country, in February and June.

Small local businesses no longer pay the “rent” demanded by these groups, neighbors once again cross the lines – invisible, but well known to them – that delimited opposing territories, and food deliverers arrive in those communities that for years were impenetrable to outsiders and police.

“My children couldn’t play in the street or in the parks. They grew up locked up,” Audelia Rosales, a teacher who has lived in one of those neighborhoods, La Campanera, since the 1990s, told the BBC.

These are places that are beginning to lose their violent image. “For years I didn’t say where I lived. Many times people couldn’t find work because the stigma of living here was great. But now I do say it with pride.”

These are the results that have turned Bukele into an international media figure and a model of anti-violence policies for certain sectors of politics beyond his country.

And from the borders inward, it has earned him an overwhelming 92% favorable opinion, according to a CID Gallup poll last January.

“More than 90% of the population agrees with the state of emergency and wants it to be extended, and the only ones who complain are the activists who don’t know what is happening in the country and the political opposition,” El Salvador’s vice president told the BBC during an interview five months ago.

Felix Ulloa

He also denied that law enforcement is detaining citizens just because they have tattoos or because of an anonymous call.

Although he acknowledged that, with an operation of this size underway, it is possible that some mistakes have been made and some people arrested without links to the Mara Salvatrucha or Barrio 18. He added that thousands have already been released, “after review following due process in the courts” and proof “that they have had no links to the gangs.

Meanwhile, during its visit to the country, BBC Mundo found that talking about human rights violations seems secondary for many Salvadorans, who focus on highlighting the evident improvement in the security of a nation that, after suffocating with a rate of 106.3 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants in 2015, closed 2022 with 7.8, according to official figures.

But for some families the issue has been more complex than they expected.

I used to tell my husband that now, with the regime, everything was going to be fine, because we lived in one sector (controlled by one gang) and worked in another (sector dominated by the other),” “Mariona”, a woman who for years suffered harassment from these groups, told us at the gates of the La Esperanza Penal Center in the capital, “Mariona”.

She asks for half a day off from work and arrives every Wednesday with her two children to ask about her husband, who is in the penitentiary and has not been heard from for months.

“Who would have told me that in a few weeks they would take him away?” he laments.

“People don’t care if the rights of others are violated, as long as they are safe and well,” says Antonio Durán, the second sentencing judge in Zacatecoluca.

“But the thing about guarantees is that they are intersubjective: to the extent that others are protected, so are we. And to the extent that others are unprotected, to that same extent, we all are.”

Images, photos, and 3D animation are available at the source…

BBC News: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/resources/idt-051ab38e-b7d2-44ce-b40f-80d5b51f7db2

El secretismo que rodea al Cecot, la megacárcel símbolo de la guerra de Bukele contra las pandillas

Angélica dice que tenía ya un presentimiento, pero fue aquel video el que confirmó sus sospechas.

Lo habían compartido en un grupo de Facebook y lo revisó con paciencia, cuadro a cuadro.

Pasado el minuto 25, al ver a aquel hombre sentado con las piernas cruzadas estrecharle la mano a su vecino de litera, lo paró en seco. Retrocedió y dejó avanzar unos segundos antes de volver a pulsar stop .

Aunque tuviera la cabeza rapada y estuviera vestido, como el resto de los presos, únicamente con una calzoneta blanca, no tuvo dudas: era su marido Darwin.

No lo había visto desde su detención el 30 de marzo de 2022, hacía ya 11 meses.

Esas imágenes eran la primera prueba de que había sido trasladado al Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo (Cecot) , la megaprisión inaugurada por el presidente Nayib Bukele el 31 de enero de 2023, que se ha convertido en un símbolo de su “guerra contra las pandillas” y de la política de seguridad que le ha dado una popularidad sin precedentes a nivel nacional e internacional.

El apoyo a Bukele se basa sobre todo en la drástica reducción de homicidios que se ha registrado desde que comenzó su gobierno en el que llegó a ser el país más violento del mundo.

Son muchos los que destacan ese cambio y respiran aliviados, sobre todo en los barrios antes controlados por las pandillas, donde “ver, oír y callar” era la regla, y los vecinos pueden ahora cruzar las fronteras invisibles que estas impusieron históricamente sin sufrir hostigamiento y sin miedo a represalias.

Sin embargo, cinco meses después de su inauguración, el Cecot es también un exponente del hermetismo y las acusaciones de opacidad del régimen de excepción aprobado tras 76 asesinatos registrados en solo 48 horas en marzo de 2022.

Desde que comenzó, casi 70.000 personas han sido detenidas, una serie de garantías están suspendidas y existen numerosas denuncias de graves atropellos a los derechos humanos, desde arrestos arbitrarios y torturas hasta muertes bajo la custodia del Estado.

Son miles los salvadoreños que llevan meses sin saber de sus familiares detenidos y que, como Angélica, los buscan en videos, fotografías, o asomándose a pequeños agujeros en los muros de las prisiones a las que logran acercarse.

El Cecot fue presentado a los salvadoreños en cadena nacional de radio y televisión, como “la cárcel más grande de toda América”.

Tiene, según el gobierno, capacidad para 40.000 presos , y es exclusiva para los “perfilados como altos rangos” de la Mara Salvatrucha (o MS-13) y las dos facciones del Barrio 18, pandillas rivales que fueron aumentando su poder durante décadas con el reclutamiento de jóvenes y el control de territorios, y sembraron terror, división y muerte en la nación centroamericana.

Tras aparecer en los medios recorriendo sus instalaciones, Bukele la destacó en Twitter, su plataforma favorita para promocionar los resultados de su administración:

“El Salvador ha logrado pasar de ser el país más inseguro del mundo, al país más seguro de América”.

“¿Cómo lo logramos? Metiendo a los criminales en la cárcel. ¿Hay espacio? Ahora sí. ¿Podrán dar órdenes desde adentro? No. ¿Podrán escapar? No. Una obra de sentido común,” agregó.

Con un despliegue mediático similar, el 24 de febrero se anunció la entrada de 2.000 internos a la prisión y el 15 de marzo el de otros tantos, los dos únicos traslados de los que se tiene conocimiento público hasta la fecha.

Entre esas imágenes oficiales de hombres semidesnudos a ratos corriendo agachados, a ratos sentados muy pegados, fue que identificó Angélica a su marido, un hondureño que había sido deportado de EE.UU. en 2018 tras cumplir una condena por robo y que posteriormente emigró a El Salvador, donde no cuenta con antecedentes penales.

“Lo reconocí por los tatuajes”, los mismos que, según le dice a BBC Mundo, llevaron a su arresto por “agrupaciones ilícitas”, un delito que en El Salvador abarca no solo a los que lideran o participan en las pandillas sino a quienes obtienen “provecho indirectamente” de las relaciones con ellas, sea cual sea su naturaleza.

Es por esa grabación —y porque tiene un recibo que prueba que ingresó ante la Dirección General de Centros Penales US$90 para gastos de su marido en la cárcel— que está convencida de que su esposo pasa sus días en una de las 256 celdas de la gigantesca prisión.

Tras la bullada apertura, pero antes de los traslados de prisioneros, varios medios ingresaron al Cecot, pero la información pública de las condiciones en que viven los allí ingresados es escasa, si no inexistente .

BBC Mundo recibió una negativa a su solicitud de visitarla. Y hasta el momento de publicación de este reportaje, la entrevista pedida al presidente Bukele u otro representante del Ejecutivo para hablar de las preguntas surgidas en los últimos meses sigue “pendiente”.

Pero a partir de videos (del gobierno y de la prensa) fotografías, entrevistas con autoridades y datos contrastados por un técnico involucrado en la construcción y cuya identidad no revelamos por seguridad, hemos recreado detalles de la megacárcel para intentar dar mayor contexto de su dimensión.

Los metros cuadrados que cada preso tendría es precisamente una de las interrogantes sobre la que BBC Mundo no ha obtenido respuesta.

De acuerdo a lo afirmado por Héctor Saldaña, ingeniero de Centrales Penales de El Salvador, en una entrevista con la revista colombiana Semana realizada dentro del Cecot, “cumplimos las normas internacionales a nivel latinoamericano (…) Damos el cumplimiento de más de 2,5 metros cuadrado por privado de libertad”.

Pero planos vistos por BBC Mundo indican que cada celda mide 7,4 por 12,30 metros, es decir 91,02 metros cuadrados, lo que se traduce en apenas 0,58 metros cuadrados por persona.

El Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja recomienda 3,4 metros cuadrados por prisionero en una celda grupal, según la última edición de su guía sobre agua, saneamiento, higiene y hábitat en prisiones.

Esas recomendaciones están dirigidas a autoridades de todo el mundo, si bien la Cruz Roja mantiene conversaciones privadas y unilaterales con gobiernos y esos intercambios, así como cualquier recomendación específica, tienen carácter confidencial.

Esto es especialmente relevante si se toma en cuenta que aunque en videos oficialistas ha aparecido una fábrica en que los prisioneros trabajarían eventualmente, las mismas autoridades han explicado que las celdas están concebidas para que los presos pasen ahí el mayor tiempo posible, y solo salgan para ir a la sala de audiencias por videoconferencia o a aislamiento.

En las celdas comunes, la luz natural proviene de los tragaluces, las celosías y los techos curvos de los pabellones, que son también la única fuente de ventilación en un país en el que la temperatura puede superar los 30 grados centígrados, con una humedad relativa del 60%.

En el calabozo de castigo solo hay una plancha de cemento que hace de cama, una pila de agua, y un retrete.

El viceministro de Justicia y director general de Centros Penales, Osiris Luna, señaló en un video promocional que el preso que sea llevado ahí irá esposado y permanecerá casi a oscuras, salvo por un pequeño y redondo orificio en el techo.

A la fecha se desconoce si hay reclusos viviendo en esas condiciones.

En el Cecot “ no se han construido patios , no se han construido áreas de recreación para los reos”, informó en su momento el ministro de Obras Públicas, Edgar Romeo Rodríguez Herrera, lo que contraviene lo dictado por las Reglas Mínimas para el Tratamiento de los Reclusos, aprobadas en 2005 por la Asamblea General de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas (ONU).

También llamadas Reglas Nelson Mandela en homenaje al expresidente sudafricano —quizá el preso más conocido del siglo XX—, estas normas proporcionan a los Estados directrices para proteger los derechos de las personas privadas de libertad.

Y establecen, entre otras cuestiones, que “todo recluso deberá tener por lo menos una hora diaria de ejercicio adecuado al aire libre” (regla 23).

En el nuevo complejo penitenciario tampoco hay espacios conyugales, a diferencia de otros centros penales. “No hay visita íntima ni visitas familiares. Eso está prohibido para este tipo de personas”, zanjó el viceministro Luna en el recorrido televisado en el que acompañó a Bukele.

Esas descripciones oficiales despiertan preocupación entre expertos.

“No tener comunicación con la familia hace que su sanción se extienda a personas inocentes”, le dice a BBC Mundo Miguel Sarre, exmiembro del Subcomité de las Naciones Unidas para la Prevención de la Tortura y alguien con amplia experiencia en la supervisión de sistemas penitenciarios.

- No se sabe exactamente cuántos presos hay , si solo los 4.000 que se vieron en los videos de los dos traslados o si hubo otros traslados que no fueron difundidos.

- Los criterios para los traslados al Cecot no son públicos y hay dudas sobre la identidad de quiénes están presos allí, si fueron detenidos durante el régimen de excepción o son pandilleros que estaban cumpliendo condena en otras cárceles.

- No se conocen detalles sobre las rutinas de alimentación; cuándo, dónde y qué comen los internos. Ni si en las instalaciones hay cocina, comedor, enfermería o tienda.

- Lo que sí se sabe es que para edificarlo el gobierno adquirió 166 hectáreas en las cercanías de Tecoluca, un municipio del departamento central de San Vicente.

- Se encuentra a unos 74 kilómetros al sureste de la capital, San Salvador, en un entorno rural en que viven unas cuantas comunidades que trabajan sobre todo en plantaciones de maíz y frijol.

- La cárcel se construyó en menos de un año.

- Los expertos calculan que en otras circunstancias tomaría tres años.

La información sobre los procesos de licitación y asignación de las obras, así como de los costos de construcción y funcionamiento, fue declarada bajo reserva por parte del gobierno.

Una serie de leyes aprobadas por la Asamblea Legislativa —controlada por el oficialismo— permite acelerar dichos procesos y disminuye los controles sobre ellos.

El ministro de Justicia y Seguridad Pública, Gustavo Villatoro, explicó en una entrevista con Americano Media en febrero que fue posible construirla en 7 meses “gracias a unir los constructores más grandes que tiene el país y ponerlos en función de generar esto en tan corto plazo (…) Muchas obras de construcción, de desarrollo urbanístico o de torres de apartamento en el país se quedaron sin mano de obra y en algún momento de la construcción incluso nos quedamos sin cemento a nivel nacional, porque todo lo estaba absorbiendo la construcción de este megacentro penal”.

Ese mismo mes, poco después de la inauguración del Cecot, la BBC tuvo la oportunidad de hablar con él.

“Para nosotros, representa el mayor monumento a la Justicia que jamás hayamos construido. No hay nada que esconder”, dijo en esa entrevista.

“Ahí van a ir los miembros de estas organizaciones terroristas. Ese no es lugar para detención de base social, de colaboradores. Los colaboradores van a estar en otras cárceles, donde van a tener programas de rehabilitación, para poder trabajar. Cecot, los que vayan ahí, tenemos un compromiso con los salvadoreños de que no vuelvan nunca, de que no regresen a las comunidades. Y nos vamos a encargar de armar los casos necesarios para que no vuelvan”.

Gustavo Villatoro, ministro de Justicia y Seguridad Pública.

Cuatro meses después de esas declaraciones, volvemos a El Salvador y viajamos hasta las inmediaciones del centro penal.

Nos detenemos a comprar agua en una venta de comida y bebidas, la única en kilómetros a la redonda, estratégicamente situada en el cruce de la carretera principal a Tecoluca y la calle que lleva al Cecot.

Ya a primera hora —y eso en El Salvador es las seis de la mañana— hay allí, tomando café, media decena de custodios que trabajan en la cárcel y policías y militares de los retenes de alrededor.

Desde una de sus mesas de plástico podemos observar, a unos 500 metros, uno de esos controles para acceder a las instalaciones de la prisión, que solo personal autorizado puede cruzar.

Sentado junto a nosotros, un policía con gafas oscuras apura su taza y nos confirma que desde enero ha aumentado el personal de seguridad en la zona.

“Ni El Chapo (Guzmán, conocido por sus sonadas huidas de cárceles de máxima seguridad) podría escapar de ahí”, asegura, haciéndose eco del discurso del gobierno sobre la faraónica obra.

Un poco antes del mediodía, cuando ocho mujeres no den abasto llenando la pila de envases de polietireno con el pollo asado, el arroz y las dos tortillas que servirán de almuerzo al personal del Cecot, tomaremos el camino sin asfaltar que lleva a la comunidad del Buen Amanecer.

Y desde esta zona de casas de lámina y suelo de tierra, a la que sus habitantes se mudaron hace unos dos años porque les cedieron el terreno pero no las escrituras, distinguiremos entre los árboles y bajo el imponente volcán Chichontepec un par de torres de vigilancia de la megacárcel y el brillo del techo abovedado de los pabellones.

Es imposible acercarse más.

- El complejo penitenciario tiene 23 hectáreas edificadas .

- Cuenta con 8 pabellones o módulos de 5.446 metros cuadrados con 32 celdas cada uno.

- Dos cercos perimetrales de seguridad con malla ciclón, totalmente electrificados, y dos muros de concreto armado rodean las instalaciones. Hay 19 torres de vigilancia .

- El ministro Villatoro destacó que las instalaciones y los presos serán vigilados por 1.000 custodios y 250 efectivos de la Policía Nacional Civil (PNC)…

- …y 600 miembros de las Fuerzas Armadas se encargarán de cuidar el anillo exterior.

Acabado ya su descanso y antes de dirigirse a su puesto, el policía de las gafas de sol admite que su vida ha mejorado considerablemente en los últimos meses.

“Antes tenía que ir a sacar a los pandilleros a sus casas, con lo que eso implicaba. Ahora me paso el día en los retenes y de vez en cuando tengo tiempo de tomarme un café”.

Policía

Su estado de ánimo contrasta con el de María, de 23 años, a la que encontramos no muy lejos de allí, en su casa de El Maniadero, otra de las comunidades de los alrededores.

Su madre no está. Desde que arrestaron por “agrupaciones ilícitas” a su pareja, quien paradójicamente trabajó durante seis meses en la construcción del penal, suele ir al mercado a hacer y vender tortillas de lunes a viernes.

“Yo voy los fines de semana”, nos cuenta la joven, sentada junto al fuego en el que luego preparará la comida y que eleva a la máxima potencia el calor pegajoso del mediodía.

“El resto del tiempo lo paso en la casa o donde mi tía”.

No se arriesga a salir, dice, por miedo a que le pase lo de su padrastro o su amiga Jessica, a la que la policía se llevó bajo el régimen de excepción dejando atrás una niña de 3 años.

“Parece que ser joven es hoy delito en El Salvador”]

María

La de las detenciones es —junto a los rumores sobre que el agua corre sucia en el arroyo desde la construcción del Cecot y de que en algún momento los desalojarán porque van a levantar un penal para mujeres en el área— una conversación recurrente entre los vecinos los barrios construidos sobre lo que antes fue la vía del tren.

68.294 personas han sido apresadas desde que se inició el régimen de excepción, de acuerdo a cifras del 4 de mayo del Ministerio de Seguridad, las más recientes.

Y aunque el Cecot es la cárcel más simbólica, la mayoría de los arrestados no está ahí, sino en alguna otra prisión en detención preventiva. Algunos llevan meses, hasta más de un año, en esa situación.

Ya antes de esos arrestos, El Salvador encabezaba las estadísticas globales de los países que más encarcelan y su sistema penitenciario sufría de hacinamiento crónico.

Tanto, que en 2016 la Corte Suprema salvadoreña declaró inconstitucional la situación de abarrotamiento en las cárceles, estableciendo que vulneraba “el derecho fundamental a la integridad personal”.

Para tratar de aliviar la sobrepoblación, entre abril de 2015 y marzo de 2019 se inauguraron nueve centros que aumentaron la capacidad del sistema penitenciario en 16.296 plazas.

Pero fue como poner tiritas a una hemorragia arterial.

“Aquí entran sanos y salen enfermos”, nos dice un policía que habla apretando los dientes mientras hace guardia en la entrada del Centro Penal La Esperanza, más conocido como “Mariona”.

Nos hemos acercado a preguntar al escuchar que un hombre viene a recoger a un interno al que tuvieron que cortarle el pie por una complicación derivada de su diabetes y que va a salir libre esa misma tarde.

El Cecot es la primera cárcel construida en el gobierno de Bukele , y él ha insistido en que tiene a su servicio la tecnología punta de una prisión “del primer mundo”, con sistemas de escaneo a la entrada para detectar cualquier objeto ilegal que traten de introducir los detenidos y una vasta red de vigilancia y control, que incluye una sala de armas con numeroso arsenal.

Pero no todos comparten su visión.

“Aunque tenga algunos elementos más avanzados, no es moderna”, rebate Abraham Ábrego, director de litigio de Cristosal, la principal organización de defensa de los derechos humanos de la sociedad civil en El Salvador.

“No es novedosa en cuanto a mecanismos de reinserción, de rehabilitación. Es básicamente un mecanismo de castigo, meramente punitivo, y esa es una lógica medieval, no un ejercicio moderno”, afirma.

Abraham Ábrego

Antonio Durán, juez segundo de sentencia de Zacatecoluca y uno de los pocos magistrados abiertamente crítico con la administración Bukele y su régimen de excepción, concuerda y va más allá.

“En un Estado de derecho la privación de libertad es el castigo. Se castiga al delincuente privándolo de libertad”, le dice a BBC Mundo.

“Pero aquí se entiende que se le priva de libertad para ser castigado adentro de la prisión. Y eso no solo es erróneo sino que además es delictivo. Es tortura”.

“Si una no anda detrás de su familiar, puede que se muera y una no se entere”.

Ángeles cree que su hermano está en el Cecot porque lo reconoció, como Angélica a su esposo, en las imágenes de uno de los traslados de presos a la megacárcel.

“Abrí mi Facebook y ahí lo vi, todo golpeado, casi desnudo, en boxer, y me puse muy mal”, cuenta sentada en su casa de Santa Ana, unos 70 kilómetros al oeste de la capital.

Está exhausta tras pasar el día comprando mercadería para la venta informal.

Retirado de la pandilla en 1995 —asegura la mujer—su hermano llevaba años regentando una pequeña tienda en ese mismo barrio cuando el 13 de abril de 2022 varios agentes llegaron a su casa y se lo llevaron a comisaría.

No volvió a saber de él. Hasta que lo identificó en la red social.

Glenda y Heidy están convencidas de que su hermano y su marido, respectivamente, corrieron la misma suerte. También fueron arrestados en abril de 2022, y llevados primero a la delegación policial, luego a la cárcel de Izalco.

Ellas no los han identificado en ningún video, pero creen haber obtenido otro tipo de corroboración de que están en el Cecot.

“Yo llamé y llamé y en una de esas uno de los custodios me lo confirmó. Y también mandé a una persona a verificar al penal si era cierto que lo habían movido. Me quedé con la boca abierta cuando me contaron”, detalla Glenda.

El rastreo ha sido particularmente difícil para estas mujeres que viven en Estados Unidos. “Pero si una no anda detrás de su familiar apresado, puede que se muera y una no se entere”, sigue Glenda, quien se niega a resignarse.

“Esas son las únicas vías de información, las informales . No hay notificación formal del traslado en ninguno de los casos”

Ricardo Bolaños, abogado y activista que colabora con el Movimiento de Víctimas del Régimen (Movir).

BBC Mundo habló con decenas de familiares de apresados bajo el régimen de excepción y el relato se repite.

Muchos, sobre todo hombres, han sido sacados de sus casas sin que les mostraran orden de allanamiento o de detención, llevados a una audiencia virtual junto con decenas de detenidos y el juez dictó prisión preventiva mientras la Fiscalía investiga si hay pruebas para una acusación formal.

Tras una serie de reformas legales, actualmente esa fase de instrucción se puede alargar meses, incluso años.

“Al principio la gente creía que su familiar iba a regresar a los 15 días. Luego, que a los seis meses. Después de la detención comienza el calvario para las familias: van al puesto de la delegación policial más cercano, a la primera cárcel, a la segunda, a la Procuraduría…”, explica Zaira Navas, ex inspectora general de la Policía y actual coordinadora de Cristosal en el análisis del régimen de excepción.

“Además, no hay un registro centralizado donde la familia pueda llegar y decir: ‘Me detuvieron a mi hijo en el departamento de Usulután y quiero saber en qué penal está”, prosigue.

BBC Mundo pudo atestiguar esa angustiosa búsqueda cuando recorrió distintas cárceles y habló con salvadoreños que llegan hasta las mismas puertas cada semana a preguntar por sus familiares detenidos, esperan sentados durante horas como en la de Apanteos, o miran por los agujeritos del muro exterior cada vez que hay traslado de presos, como en la de Ilopango.

Navas encabeza un equipo que investiga cientos de denuncias por posibles violaciones de derechos humanos durante el periodo de excepción.

El informe que presentaron el 29 de mayo, elaborado a partir de una exhaustiva investigación y que dio la vuelta al mundo, concluye que en el primer año de dichas medidas decenas de reos han muerto por torturas, golpes o falta de atención sanitaria en las cárceles del país.

El gobierno no ha respondido de forma pública al informe. Pero el comisionado de Derechos Humanos Andrés Guzmán Caballero, quien asumió el cargo el 24 de mayo, reconoció tras ser cuestionado durante un evento en el que participaba por el medio salvadoreño La Prensa Gráfica que el reporte es “preocupante”.

“Cerramos el 10 de mayo de 2023 con 0 homicidios a nivel nacional. Con este, son 365 días sin homicidios, todo un año”, anunció Bukele en Twitter durante esa jornada.

Pasaron cinco días y un policía muerto rompió la estadística.

“Los pandilleros que aún quedan en nuestro país acaban de asesinar a uno de nuestros héroes” , tuiteó entonces el presidente salvadoreño.

“Pero ahí no dirán nada las ONG de ‘derechos humanos’, ellos solo velan por los derechos de los criminales. ¿Ven por qué debemos continuar con el régimen de excepción hasta terminar por completo con esta peste? Este cobarde asesinato no quedará impune. Los haremos pagar caro lo que hicieron” , prosiguió.

Y a las horas insistió: “Que sepan todas las ONG de ‘derechos humanos’ que vamos a arrasar con estos malditos asesinos y sus colaboradores, los meteremos en prisión y no saldrán jamás”.

Esa combinación de tuits es un buen reflejo de la política de seguridad impulsada por Bukele, quien encabeza el Ejecutivo salvadoreño desde julio de 2019.

El suyo no es el primer gobierno de El Salvador con estrategias de “mano dura”, pero con su guerra frontal ha conseguido desarticular las pandillas, tal como lo proclaman funcionarios y lo reconocen expertos y organizaciones en terreno.

Las pandillas “tenían territorio, población, impartían justicia, con armas, pero impartían justicia, tenían recaudación… Definitivamente luchamos contra un Estado paralelo, y ese Estado paralelo, para bien de los más de 6 millones de salvadoreños, está destruido”, le dijo el ministro de Seguridad, Gustavo Villatoro, a la BBC en la entrevista concedida a principios de año.

Es algo evidente en las calles, como pudo comprobar BBC Mundo en dos visitas al país, en febrero y junio.

Los pequeños negocios locales ya no pagan la “renta” exigida por estos grupos, los vecinos vuelven a cruzar las líneas — invisibles, pero que ellos conocían bien—que delimitaban territorios contrarios y los repartidores de comida llegan a esas comunidades que durante años fueron impenetrables para foráneos y la policía.

“Mis hijos no podían jugar en la calle o en los parques. Crecieron encerrados”, le contó a la BBC Audelia Rosales, una maestra que vive en uno de esos barrios, La Campanera, desde la década de los 90.

Son lugares que empiezan a perder su imagen violenta. “Durante años no dije dónde vivía. Muchas veces la gente no encontraba trabajo porque el estigma de vivir aquí era grande. Pero ahora sí lo digo con orgullo”.

Son estos los resultados que han convertido a Bukele en toda una figura mediática internacional y un modelo de las políticas contra la violencia para ciertos sectores de la política más allá de su país.

Y de fronteras para adentro le ha valido un aplastante 92% de opinión favorable , según una encuesta de CID Gallup del pasado enero.

“Más del 90% de la población está de acuerdo con el estado de excepción y quiere que se extienda, y los únicos que se quejan son los activistas que no saben qué ocurre en el país y la oposición política”, le contestó el vicepresidente de El Salvador a la BBC durante una entrevista hace cinco meses.

Félix Ulloa

También negó que las fuerzas del orden estén deteniendo a ciudadanos solo por tener tatuajes o por una llamada anónima.

Aunque reconoció que, con una operación de esas dimensiones en marcha, es posible que se haya cometido algún error y arrestado a algunas personas sin vínculos con la Mara Salvatrucha o el Barrio 18. Y añadió que miles ya fueron liberados, “tras revisarlo siguiendo el debido proceso legal en los tribunales” y probarse “que no han tenido vínculo alguno con las pandillas”.

Mientras, en su visita al país, BBC Mundo constató que hablar de vulneraciones de derechos humanos parece secundario para muchos salvadoreños, quienes se centran en destacar la evidente mejoría en la seguridad de una nación que, tras asfixiarse con una tasa de 106,3 homicidios por cada 100.000 habitantes en 2015, cerró 2022 con 7,8, según cifras oficiales.

Pero para algunas familias el tema ha sido más complejo de lo que esperaban.

“Yo le decía a mi marido que ahora, con el régimen, todo iba a ir bien, porque vivíamos en un sector (controlado por una pandilla) y trabajábamos en otro (sector dominado por la contraria)”, nos contó a las puertas del capitalino Centro Penal La Esperanza, “Mariona”, una mujer que durante años sufrió hostigamiento por parte de estos grupos.

Pide libre medio día en el trabajo y llega cada miércoles con sus dos hijos a preguntar por su esposo, quien se encuentra en ese centro penitenciario y del que hace meses no sabe nada.

“¿Quién me iba a decir que en unas semanas se lo iban a llevar a él?”, se lamenta.

“A la gente no le importa que se violen los derechos de los demás, siempre y cuando ellos estén bien y seguros”, comenta sobre esto Antonio Durán, el juez segundo de sentencia de Zacatecoluca.

“Pero la cuestión de las garantías es que son intersubjetivas: en la medida que los demás están protegidos, también lo estamos nosotros. Y en la medida en que los demás están desprotegidos, en esa misma medida, todos lo estamos”.

Imágenes, fotos y animación 3D están disponibles en la fuente…

BBC News: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/resources/idt-051ab38e-b7d2-44ce-b40f-80d5b51f7db2