The prosecutors tracking Nayib Bukele for more than a year received calls on Saturday, May 1, 2021. The caller was Raul Melara, their boss, to recommend they secure all the documents they had collected during an investigation implicating the president and his close circle in various crimes. Afterward, Melara took from his office a poster board on which his subordinates had outlined a criminal organization that operated in the Salvadoran state, at the head of which they had placed Bukele and his three brothers. Melara left his office, never to return.

Until that day, Raul Melara was El Salvador’s attorney general, but he knew that was about to end. Someone close to Bukele’s presidential palace had warned him that same day that the president and the newly elected deputies of the ruling party had the plan to get him and several magistrates of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice out of the way.

Both the investigations that Melara and his subordinates were involved in, which were captured in the files from which the outline that the attorney general took from his office emerged, and what happened on May 1, 2021, were transmitted to federal agents in the United States, who took everything as part of their investigations into corruption cases involving Salvadoran officials and Bukele’s pact with the MS13 and Barrio 18 gangs. The gang dealings were also being investigated by a US task force called Vulcano, which involves FBI and DEA agents. Infobae has had access to files from that investigation, the authenticity of which it confirmed with two U.S. agents familiar with it and two former Salvadoran investigators who received reports about it.

Every three years, on May 1, a new legislature takes office in El Salvador. The one elected in the February 2021 elections gave Bukele a supermajority in the Assembly: 56 deputies from Nuevas Ideas, the party managed by relatives of the president, and eight from minor parties aligned with him; 64 in a parliament of 84 deputies. One of the first acts of the new Congress was to get rid of Attorney General Melara and the five magistrates.

The whole thing, the departure of the attorney general investigating the president and the magistrates, was planned in the presidential house. One of the prominent managers of the plot was Javier Argueta, a lawyer close to Ernesto Castro. Until May 1, 2021, the president’s private secretary has been president of Congress since then. Based in part on what the Vulcan task force had investigated, the US government listed Argueta as a corrupt and anti-democratic official on the Engel List, as the report in which the State Department singles out such Central American officials is called.

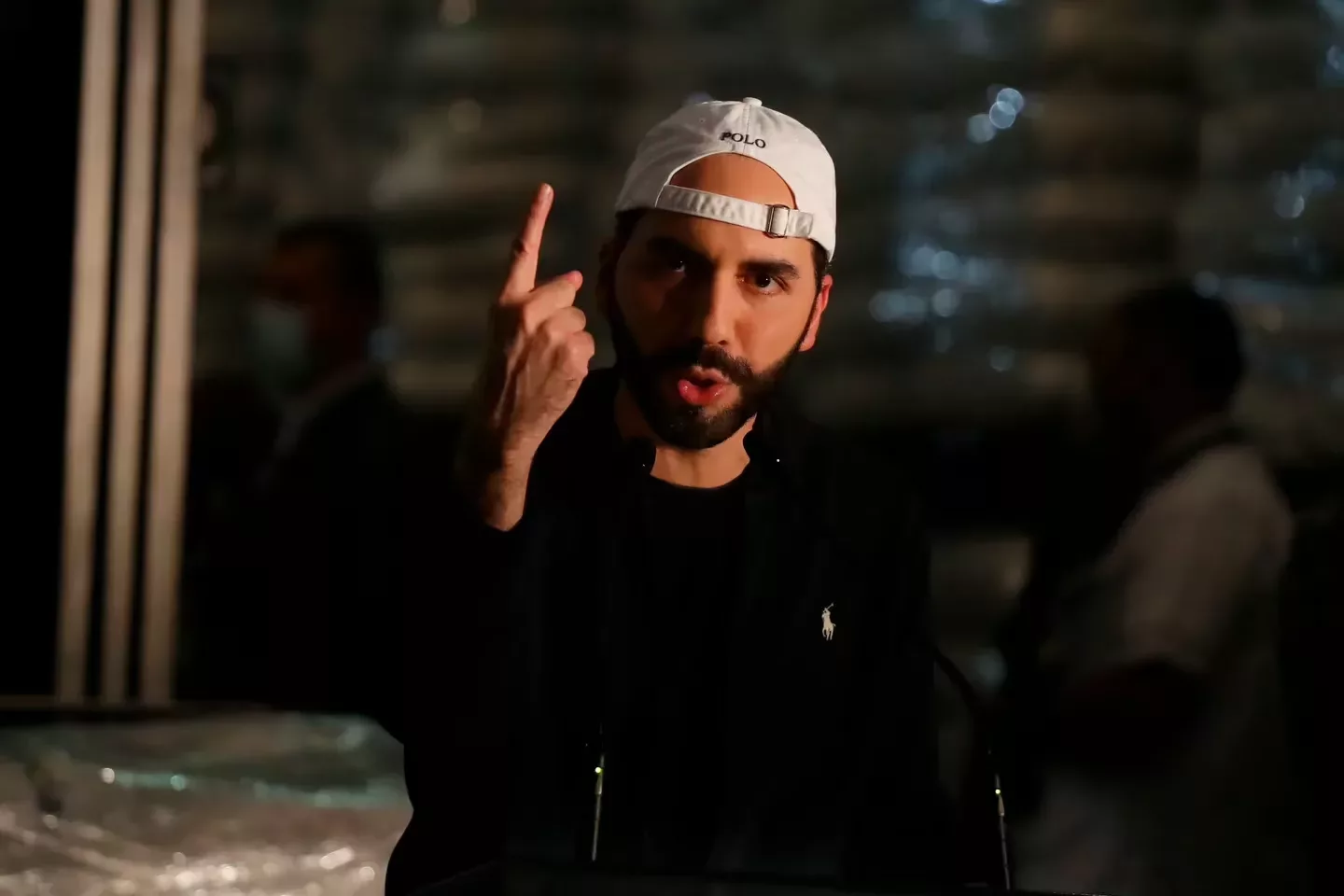

In July 2018, when Bukele was leading in the polls, journalist Fernando del Rincón of CNN interviewed him. There, the Salvadoran aspirant was emphatic in criticizing Daniel Ortega’s model in Nicaragua, specifically the concentration of power and the control of one person of all the management of the State. The only way out for the Nicaraguan to stay in power, Bukele said, was to “resign” or “maintain a constant crisis.”

Fast forward three years: on September 15, 2022, after a controversial interpretation of the Constitution made by the Supreme Court to which Bukele had illegally installed in 2021, the Salvadoran president announced that he would run for reelection in the 2024 elections, although the primary law of El Salvador expressly forbids it. Del Rincón, the CNN journalist, made a program to talk about the issue on September 21: “You can love the president for what he is doing, but a person who does not keep his word for a power issue, to perpetuate himself in power… Do you want that? When a dictator comes in front and tells you he is going to be a dictator,at least he has integrity, but when someone tells you he is going to be a democrat and then changes his speech, he has neither integrity nor principles.”

Today, Bukele walks unhindered to reelection, supported by a Judicial Power he took control of in 2021 and a popularity index that does not go below 80%. El Salvador, says the official propaganda, is safer today thanks to the mega-prison and the limitation of constitutional guarantees, not to the pact with gang leaders that, among other things, shielded them from extradition to the United States. But the Central American country is also today one in which whoever is captured by the police is not guaranteed the right to defense and can spend up to two weeks without seeing a judge, one that has already expelled journalists critical of the president, one that, as defined by the University of Gothenburg, is in a transition towards an autocracy.

El camino de Nayib Bukele hacia el autoritarismo cool: de una selfie en la ONU a invocar diálogos con Dios

Los fiscales que le habían seguido la pista a Nayib Bukele durante más de un año recibieron llamadas el sábado 1 de mayo de 2021. Quien les llamaba era Raúl Melara, su jefe, para recomendarles asegurar todos los documentos que habían recopilado durante una investigación que implicaba al presidente y su círculo cercano en varios delitos. Después, Melara tomó de su despacho una cartulina en la que sus subalternos habían dibujado el esquema de una organización criminal que funcionaba en el Estado salvadoreño, a la cabeza de la cual habían ubicado a Bukele y a sus tres hermanos. Melara salió de su despacho para no volver.

Hasta aquel día, Raúl Melara era el fiscal general de El Salvador, pero él sabía que eso estaba a punto de terminar. Alguien cercano a la casa presidencial de Bukele le había advertido, ese mismo día, que el presidente y los recién electos diputados del oficialismo tenían un plan para apartarlo del camino a él y a varios magistrados de la Sala Constitucional de la Corte Suprema de Justicia.

Tanto las investigaciones en las que estaban embarcados Melara y sus subalternos, que quedaron plasmadas en los expedientes de los que salió el esquema que el fiscal general se llevó de su despacho, como lo ocurrido el 1 de mayo de 2021, fue transmitido a agentes federales de los Estados Unidos, quienes retomaron todo como parte de sus propias investigaciones de casos de corrupción que implicaban a funcionarios salvadoreños y el pacto de Bukele con las pandillas MS13 y Barrio 18. El trato con las pandillas también lo investigaba una fuerza de tarea estadounidense llamada Vulcano, en la que participan agentes del FBI y la DEA. Infobae ha tenido acceso a expedientes de aquella investigación, cuya autenticidad confirmó con dos agentes de Estados Unidos que la conocen y dos ex investigadores salvadoreños que recibieron informes al respecto.

Cada tres años, el 1 de mayo, toma posesión en El Salvador una nueva legislatura. La que resultó electa en las elecciones de febrero de 2021 dio a Bukele la supermayoría en la Asamblea: 56 diputados de Nuevas Ideas, el partido administrado por familiares del presidente, y 8 de partidos menores alineados con él; 64 en un parlamento de 84 diputados. Uno de los primeros actos del nuevo Congreso fue deshacerse del fiscal general Melara y de los cinco magistrados.

Todo el asunto, la salida del fiscal general que investigaban al presidente y de los magistrados fue planificado en la casa presidencial, y uno de los principales gestores de la trama fue Javier Argueta, un abogado cercano a Ernesto Castro, quien hasta el 1 de mayo de 2021 fue secretario privado del presidente y desde entonces es presidente del Congreso. Basado en parte en lo que había investigado la fuerza de tarea Vulcano, el gobierno de los Estados Unidos listó a Argueta como funcionario corrupto y antidemocrático en la Lista Engel, como se llama al reporte en que el Departamento de Estado señala a este tipo de funcionarios centroamericanos.

En julio de 2018, cuando Bukele punteaba en las encuestas, el periodista Fernando del Rincón de la cadena CNN lo entrevistó. Ahí, el aspirante salvadoreño fue enfático en criticar el modelo de Daniel Ortega en Nicaragua, en específico la concentración de poder y el control de una persona de todos los poderes del Estado. La única salida para el nicaragüense para mantenerse en el poder, dijo Bukele, era “dimitir” o “mantener una crisis constante”.

Adelantando tres años: el 15 de septiembre de 2022, tras una polémica interpretación de la Constitución hecha por la Corte Suprema a la que Bukele había instalado de forma ilegal en 2021, el presidente salvadoreño anunció que irá por la reelección en los comicios de 2024, a pesar de que la ley primaria de El Salvador lo prohíbe de forma expresa. Del Rincón, el periodista de CNN, hizo un programa para hablar del asunto el 21 de septiembre: “Ustedes pueden amar al presidente por lo que está haciendo, pero una persona que no mantiene su palabra por un tema de poder, para perpetuarse en él… ¿Ustedes quieren eso? Cuando un dictador viene de frente y les dice que va a ser dictador por lo menos tiene la integridad, pero cuando alguien le dice que va a ser demócrata y luego cambia su discurso no tiene ni integridad ni principios”.

Hoy, Bukele camina sin obstáculos a la reelección, acuerpado por un Poder Judicial del que tomó el control en 2021 y por un índice de popularidad que no baja del 80%. El Salvador, dice la propaganda oficial, es hoy más seguro gracias a la megacárcel y a la limitación de garantías constitucionales, no al pacto con los líderes pandilleros que, entre otras cosas, los blindó de extradición a Estados Unidos. Pero el país centroamericano también es hoy uno en que quien caiga capturado por la policía no tiene garantizado el derecho a la defensa y puede pasar hasta dos semanas sin ver a un juez, uno que ya ha expulsado a periodistas críticos con el presidente, uno que, como lo define la Universidad de Goteburgo, está en transición hacia una autocracia.