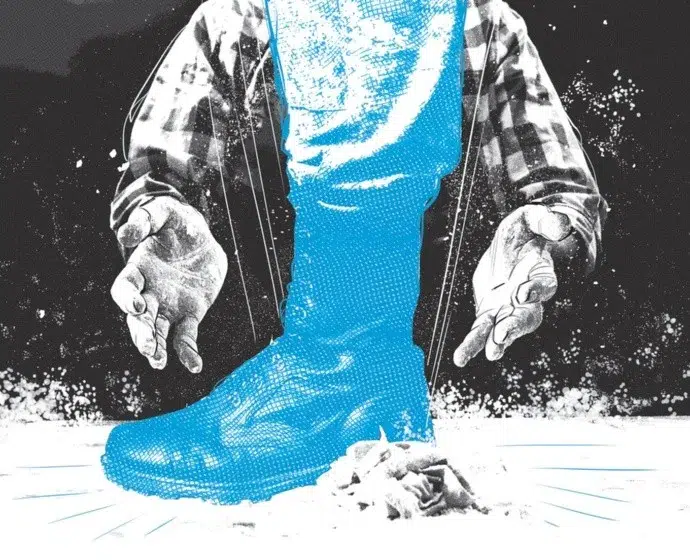

Lazarus firmly says that he is not afraid. That, however, is going to change in a few days. The emergency regime does not understand that “new birth” or things like that are said in the evangelical churches when someone repents of their past. Police forces do not understand forgiveness or redemption. For now, Lazarus has not considered hiding or leaving the country either. The tattoos he had were erased several years ago in a removal program. That number 18 in the body, which blurred the line between the old and the new man, is no longer there. But that, in El Salvador, doesn’t matter anymore.

This is told from the benches of the cafeteria of the evangelical church he directs. Here, a month ago, eight parishioners, ex-gang members like him, were captured by a police platoon. Lazarus, however, is calm. Fear, he says with the voice of a preacher who tears the words apart, is a bad companion. But those around him know that these are not the times to walk with that courage: “The brothers have asked me to hide, not to go out, not to give interviews.”

The agents went so far as to ask about the ex-gang members who lived in their church. They arrived, of course, calm. Without throwing away doors, as government propaganda usually promotes. Lazarus and the members of the reintegration project had earned the trust of the community and the authorities; therefore, this was the first time in three years that the police arrived at the church. “They called on the gate,” says Lazarus, “the auxiliary pastor who lives here came out to open them and asked them what they wanted.” The police responded that they knew that “the boys are here” and that “unfortunately” they had to take them away.

The authorities had a list. One that Lazarus had provided them years ago so they would know who the young people who were part of the reintegration program were. One of the men arrested that afternoon had been in the program for eight years and was studying his first cycle at the university. Others were studying high school thanks to the pastor’s agreement with an institute. They wanted, like their partner, to get to college. Another made banana toast that one of his companions sold to support their families. One more lived here with her two daughters. The girls, with nowhere to go, are still at the church.

Régimen de excepción desbarata esfuerzos de reinserción social

Lázaro dice con firmeza que no tiene miedo. Eso, sin embargo, va a cambiar en unos días. El régimen de excepción no entiende eso de “nuevo nacimiento” ni de cosas por el estilo que se dicen en las iglesias evangélicas cuando alguien se arrepiente de su pasado. No entiende de perdones ni de redención. Por ahora, Lázaro tampoco ha considerado esconderse o salir del país. Se borró los tatuajes hace varios años, en un programa de remoción. Ese número 18 en el cuerpo, que desdibujaba la línea entre el viejo y el nuevo hombre, ya no está. Pero eso, en El Salvador, ahora ya no importa.

Esto lo cuenta desde las bancas del cafetín de la iglesia evangélica que dirige. Aquí, hace un mes, ocho feligreses, expandilleros como él, fueron capturados por un pelotón policial. Lázaro, sin embargo, se muestra tranquilo. El miedo, dice con voz de predicador que va desgarrando las palabras, es un mal compañero. Pero quienes le rodean saben que estos no son tiempos para andar con esa valentía: “Los hermanos me han pedido que me esconda, que no salga, que no dé entrevistas”.

Los agentes llegaron a preguntar por los expandilleros que vivían en su iglesia. Llegaron, eso sí, tranquilos. Sin botar puertas, como suele promover la propaganda gubernamental. Lázaro y los miembros del proyecto de reinserción se habían ganado la confianza de la comunidad y de las autoridades; por eso, esta era la primera vez en tres años que la PNC llegaba a la iglesia. “Tocaron el portón”, cuenta Lázaro, “el pastor auxiliar que vive acá les salió a abrir y les dijo que qué querían”. Los policías respondieron que sabían que “aquí están los muchachos” y que “lamentablemente” se los tenían que llevar.

Las autoridades tenían un listado. Uno que Lázaro les había proporcionado hace años para que supieran quiénes eran los jóvenes que formaban parte del programa de reinserción. Uno de los hombres detenidos esa tarde llevaba ocho años en el programa y estaba estudiando su primer ciclo en la universidad. Otros estaban cursando el bachillerato gracias a un acuerdo que el pastor logró con un instituto. Querían, como su compañero, llegar a la universidad. Otro hacía tostadas de plátano que uno de sus compañero las vendía para mantener a sus familias. Una más vivía aquí con sus dos hijas. Las niñas, sin lugar a dónde ir, siguen en la iglesia.